Abstract

A decision theory can be useful not only as a tool for determining which action, given your desires and beliefs, is most preferable, but also as a means for analyzing the nature of rational deliberation. In this paper, I turn to two classic proposals for a causal decision theory, that of Lewis (Australas J Philos 591:5–30, 1981a. doi:10.1080/00048408112340011) and that of Sobel (Australas J Philos 64(4):407–437, 1986. doi:10.1080/00048408612342621). As Rabinowicz (Philosophical essays dedicated to Lennart Åqvist on His Fiftieth Birthday, Department of Philosophy, Uppsala, 1982) revealed, Lewis’ proposal is unable to be applied to as broad a set of decision problems as a version of CDT offered by Sobel, an account of decision theory that Lewis thought was equivalent to his own. Rabinowicz argued by offering a counterexample to Lewis’ account. In this essay, I build on that approach, offering a novel counterexample, the “Faulty Signal Problem,” which proves that Lewis’ theory fails to provide a recommendation in an even broader class decision problems than Rabinowicz recognized, particularly those that exhibit what I refer to as counterfactual asymmetries. The problem for Lewis, however, is not just a technicality. Lewis and Sobel’s theories, respectively, conceptualize rational deliberation in two different ways. Lewis’ proposal, which utilized conditionalization as its form of belief revision, shares with evidential decision theory the same underlying attitude toward the agent as evidence-maker. In contrast, Sobel’s theory, based on imaging, captures the idea that deliberation requires a distinctly suppositional attitude that respects the agent’s causal views. The Faulty Signal Problem not only gives reason to favor Sobel’s proposal over Lewis’; it also provides justification for seeing imaging as necessary for a genuinely causal decision theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For an overview of the development of CDT, see Weirich (2016).

For Lewis’ response to this criticism, see “Reply to Rabinowicz” in Lewis (1987) Note that the Lewis’ response is essentially to weaken his commitment to an imaging function that is centered for chancy worlds. The counterexample I offer does not involve chance, but, rather, backward causation. Since Lewis was committed to the possibility of backward causation, the counterexample I offer here is particularly relevant and would be difficult for Lewis to rebut in the manner he responded to Rabinowicz.

More generally, the counterfactuals may be of form \(\hbox {A}{\square }\rightarrow [\hbox {CH}(\hbox {B})=\hbox {x}]\), i.e., ‘if I were to A, then there would be a chance of x that B would occur’. Even this more general form, however, is not fully accurate, given that Lewis—in response to Rabinowicz’s criticisms—defends an account of counterfactuals where the similarity function is centered but imaging is not. Lewis’ account of centering allows for some difference between imaging and counterfactuals. In particular, he argues that if A and B are true in world w, and B is the outcome of some genuinely chancy process activated by A, then the counterfactual ‘if A, then B would occur” is true in w, even though it may be possible that the image on A of w assigns positive credence to \(\lnot B\)-worlds. Given that, as discussed below, Lewis maintains that a dependency hypotheses is an equivalence class of worlds with respect to the relation of imaging alike, this implies that a dependency hypothesis involving chancy counterfactuals cannot be reduced to conjunctions of counterfactuals. See “Reply to Rabinowicz” in Lewis (1987). Since I am not here considering a circumstance where chance is relevant, the proposed simplification is not problematic.

Joyce (1999) has also offered a version of CDT that takes imaging as primitive. Although I will not discuss Joyce’s theory in depth, his proposal would likely also be able to provide a recommendation in the Faulty Signal Problem. Further, Joyce has discussed in some depth the subjunctive nature of a genuine causal decision theory, which I discuss later in this essay.

That is not to say that a causal decision theorist should not assign any role to evidence that one’s actions provide about the state of the world. See Joyce (2012).

I will not be considering here the ongoing debate between decision theorists regarding the correct response to these types of concerns. Instead, I will take for granted that we are interested in developing a causal decision theory. EDT will only reappear in this paper for what I take to be suggestive comparisons. I do not intend to express an opinion regarding how other decision theories may address the questions posed. Still, I conclude with remarks on how these examples can inform our conception of deliberation more generally. These comments I hope can be of interest to those who do not accept the move away from EDT.

Lewis acknowledged that this suggested equivalency was not perfect, as the relation of imaging alike would partition the set of possible worlds more finely than Lewis’ dependency hypotheses. In “Reply to Rabinowicz,” Lewis specifies his understanding of the distinction in the following way: “let a practical dependency hypothesis be a maximally specific proposition about how the things the agent cares about do and do not depend causally on his present actions; let a full dependency hypothesis be a maximally specific proposition about how all things whatever do and do not depend causally on the agent’s present actions. By my definition, a ‘dependency hypothesis’ is a practical dependency hypothesis; whereas a tendency proposition is, if anything, not a practical but a full dependency hypothesis.” Lewis suggests that this distinction would have no impact on his discussion, since one could replace each reference to “practical dependency hypotheses” with reference to “full dependency hypothesis (Lewis 1987, p. 338)” Although Lewis recognized this difference between his and Sobel’s theories, it does not appear that he realized the distinction I offer below resulting from “counterfactual asymmetries,” which cannot be addressed through a finer partitioning.

Note that this constraint is justified by what Lewis calls “The Principal Principle,” which states that a rational agent’s credences are to conform to the chances. Specifically, it states that if E is some proposition about times up to and including time t and E entails that the chance of A occurring at t is x, then the agent’s credence in A at t given E must be x. Lewis refers to any evidence about the world beyond time t as ‘inadmissible’, and restricts the validity of his principle to only those agents that do not accept inadmissible evidence into their belief set. Such inadmissible evidence includes oracle predictions and time-traveling information. As we will see, it is precisely in the case of an agent who takes such evidence seriously that we will have a violation of this constraint. For more on The Principal Principle, see Lewis (1980).

I take counterfactual determinism to mean that for each of the agent’s available options, there is some determinate fact as to what the world would be like were she to choose that option. In a counterfactually deterministic world, the law of counterfactual excluded middle holds and there is no chance factored into the agent’s beliefs about what would be the effect of her actions.

For discussion of Lewis’ truth-conditions for the counterfactual and related problems, including those relating to backward causation, see Collins et al. (2004).

I will not now attempt to define the similarity criteria that yield the counterfactuals discussed here, but I will take these counterfactuals to be true and proceed by assuming the similarity relations they imply.

One may have the intuition that if Bill were to have pressed A, then the B-signal would never have been sent in the first place. This would imply that u, rather than x, is the most similar A-world to w. Such a similarity relation, however, would fail to capture the causal outlook of the agent. The agent believes that, if the signal has short-circuited, pressing either A or B would send the B-signal back in time. As referenced earlier with regard to Ramsey’s conception of the agency, deliberation (at least for those who accept CDT) involves asking not what the agent’s action reveals about the world, but what the agent believes would causally be brought about due to her volitional activity. A similarity relation that reflects the agent’s freedom to choose would hold fixed all aspects of the world that are not effects of the agent’s actions, accounting for those changes to accommodate the agent’s counterfactual action through a Lewis-style “miracle.” Such an approach would find the sort of backtracking necessary to get from w to u, i.e., if Bill pressed A instead of B, then the remote would not have short circuited, and so it would have sent signal A, inadmissible.

He need not assign zero credence to world v, but, since \(B\square \rightarrow A_S \) is only true in v, it will lie within its own dependency hypothesis. This dependency hypothesis will be assigned zero or near zero credence. I have assigned low credence to this dependency hypothesis only for the purpose of simplifying the example. The result does not depend on this stipulation. As will be discussed, the result relies on the fact that no B-world lies within the same dependency hypothesis as world.

Whether Lewis was, in fact, committed to this constraint is beyond the current discussion.

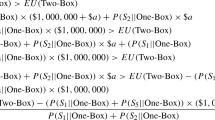

The proof from Rabinowicz (1982) is as follows: suppose that the similarity relation over worlds is centered. If \( O \& K\ne \emptyset \), then there must be some world v such that v is a O-world and K is true at v. Given that the similarity relation is centered, \(v_O^\# ( v )=1\). Since v is within the dependency hypothesis K, it follows, from imaging alike, that for any world w in which K is true, \(w_O^\# ( v )=v_O^\# ( v )\). So, \(w_O^\# ( v )=1\). Thus, since \( O \& K\) is supposed—by Lewis—to be non-empty for every option O and every hypothesis K, centering implies that the worlds are counterfactually deterministic, i.e., non-chancy, with respect to all available options. As will be made clear in the next section, this problem for K-CDT is, in fact, just a specific example of the types of cases K-CDT cannot address, i.e., those in which imaging alike fails. Note that Lewis responds to this criticism by weakening his commitment to centering, holding that while he is committed to “centering of counterfactuals,” he is not committed to “centering of the imaging function.” In essence, this implies that while Lewis acknowledges that Sobel’s theory applies to certain decision problems that his does not, i.e., problems involving chancy, centered worlds, he is not committed to the existence of such worlds and therefore does not consider the counterexample problematic. See “Reply to Rabinowicz” in Lewis (1987). An assessment of whether this response adequately addresses Rabinowicz’s concerns is beyond the scope of this essay. For the purposes of this discussion, I note that Lewis’ reply only neutralizes the counterexample Rabinowicz offers, which is based on a causal model involving chance. The counterexample I offer is non-chancy and is unusual primarily in that it involves backward causation. Since Lewis was committed to the possibility of backward causation, the sort of response offered to Rabinowicz would not be plausible here. For an argument that Lewis also fails to respond adequately to Rabinowicz, see Bales (2016) and Listwa (2015).

Note that this result cannot plausibly be avoided by stipulating some value for conditional credences of the form \(\textit{CR}(X|Y)\), where \(Y=\emptyset \). Although arbitrarily giving it some value would be an unsupported and ad hoc solution, one could conceivably seek to define the terms through some account that takes conditional probabilities to be primitive, à la Popper and Rényi. As Hájek discusses, accounts of primitive conditional probabilities are intended to avoid four “trouble spots” for the quotient-based analysis of conditional probability: “assignments of zero to genuine possibilities; assignments of infinitesimals to such possibilities; vague assignments to such possibilities; and no assignment whatsoever to such possibilities (Hájek 2003, p. 275).” The case in which a conditional probability is undefined because one conditionalizes on an empty set proposition does not fit into any of these categories. Unlike these sorts of cases, it is not intuitively the case that it is meaningful to conditionalize on an empty set proposition; the reason being that, by nature of the proposition being empty (i.e. there is no world where it is true), it is impossible for such a situation to arise where one would seek to update one’s belief on the evidence that the actual world is world where the empty set proposition holds. For this reason, I do not believe that one could defensibly avoid the result of this counterexample by drawing from an account of primitive conditionals.

This result is not challenged by the insistence that positive credence be assigned to every metaphysically possible world, as there is no metaphysically possible \( B \& K_1 \)-world. Given that a dependency hypotheses is an equivalence class of worlds with respect to the relation of imaging alike, any world in \(K_1 \) must image on B in the same way as world u. Since w is the image of u on B, then w must also be the image of any B-world in \(K_1 \) on B. Thus, if some \( B \& K_1 \)-world, call it y, existed, it would image on B to w. This, however, is metaphysically impossible. For y to image on B to w would be to say that w is the closest B-world to y. This cannot be, because y is itself a B-world and is more similar to itself than it is to world w. Note that although there is no metaphysically possible \( B \& K_1 \)-world, there is a world in which B is pressed and the remote does not short-circuit, world v in this example. As the argument just rehearsed shows, world v, does not lie in the same dependency hypothesis as world u; nor could it lie within \(K_2\). Therefore, it must lie in its own, which we could call \(K_3\). I have not addressed this third dependency hypothesis above primarily for simplicity, but note that its inclusion would not change the result of the counterexample.

We can understand ‘available’ in this context to mean that if the agent had the desire to choose the option, she would be able to do so.

Note that in the diagram above (and in the one to follow), I am unconcerned with world v, since it is assigned zero credence. It receives zero credences because it is, in a sense, a nomological impossibility. If we wanted to assign it some positive credence, we could alternatively say \(C( v )\approx 0\) with no relevant change.

Alternatively, one could say that the agent should retain uncertainty by acknowledging that one can never be entirely sure about what decisions one made in the past. Such a response might be expected of someone who took seriously the idea that every metaphysically possible world should be assigned positive credence. Unlike in the case of the Faulty Signal Problem (where the issue was the nonexistence of metaphysically possible worlds to which credence could be assigned), such a fix is available, but it seems undesirable. Intuitively, retrospective consideration of one’s past decisions does not seem to be dependent on whether one is certain that those decisions occurred or not. The idea that K-CDT would rely on such a sort of gerrymandered epistemic state in order to make sense of a mental exercise suggests that the theory does not correctly capture the nature of rational deliberation. This is the idea that I explore in the final sections of this essay.

The example can be originally found in Bennett (1988).

How this ability is retained is explained by Lewis (1981b): if determinism is true, the intervention changes either the laws or the past history in a way that retains your causal beliefs and leads your action to be other that what is was in the actual world. Suppose that determinism is true and I have just put my hand down on my desk and have refrained from raising it. I want to say that it was a free, but predetermined act. By this I mean I could have done otherwise, by raising my hand. In other words, raising my hand was an option. The fact that I did not raise my hand is entailed jointly by the distant past and the laws of nature. Therefore, if I had raised my hand, either the past or the laws would have had to have been different. This, however, does not mean that by raising my hand I would have caused either the past or the laws to be different, since that would be an obvious impossibility. Rather, something else would have caused one of the two to be different. Therefore, if I had raised my hand, either the past or the laws would have had to been different, but I would not have caused them to be different. This illustrates that the ability to do otherwise—in this case raise my hand, when I in fact did not—does not entail that I cause either the past or the law to be different.

References

Ahmed, A. (2013). Causal decision theory: A counterexample. Philosophical Review, 122(2), 289–306. doi:10.1215/00318108-1963725.

Bales, A. (2016). The pauper’s problem: Chance, foreknowledge and causal decision theory. Philosophical Studies, 173(6), 1497–1516. doi:10.1007/s11098-015-0560-8.

Bennett, J. (1988). Farewell to the phlogiston theory of conditionals. Mind, 97(388), 509–527.

Collins, J. (2015). Decision Theory after Lewis. In B. Loewer & J. Schaffer (Eds.), A companion to David Lewis. New York: Wiley.

Collins, J., Hall, N., & Paul, L. A. (eds.) (2004). Counterfactuals and causation: History, problems, and prospects. In Counterfactuals and causation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gibbard, A., & Harper, W. L. (1978). Counterfactuals and two kinds of expected utility. In Harper, W.L., Stalnaker, R. & Pearce, G. (Eds.), IFS (pp. 153–190). Dordrecht: Springer. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-009-9117-0_8. Accessed April 23, 2015.

Hájek, A. (2003). What conditional probability could not be. Synthese, 137(3), 273–323. doi:10.1023/B:SYNT.0000004904.91112.16.

Hájek, A. (2012, December). Staying regular? http://philosophy.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/Staying%20Regular.December%2028.2012.pdf

Jeffrey, R. C. (1990). The logic of decision. Chicago: University of chicago Press.

Joyce, J. M. (1999). The foundations of causal decision theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Joyce, J. M. (2012). Regret and instability in causal decision theory. Synthese, 187(1), 123–145. doi:10.1007/s11229-011-0022-6.

Lewis, D. (1976a). Probabilities of conditionals and conditional probabilities. In W. L. Harper, R. Stalnaker & G. Pearce (Eds.), IFS (pp. 129–147). Dordrecht: Springer. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-009-9117-0_6. Accessed January 29, 2015.

Lewis, D. (1976b). The paradoxes of time travel. American Philosophical Quarterly, 13(2), 145–152.

Lewis, D. (1979). Counterfactual dependence and time’s arrow. Noûs, 13(4), 455–476. doi:10.2307/2215339.

Lewis, D. (1980). A subjectivist’s guide to objective chance. In W. L. Harper, R. Stalnaker & G. Pearce (eds.), IFS (Vol.15, pp. 267–297). The University of Western Ontario Series in Philosophy of Science, Springer Netherlands. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-009-9117-0_14.

Lewis, D. (1981a). Causal decision theory. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 59(1), 5–30. doi:10.1080/00048408112340011.

Lewis, D. (1981b). Are we free to break the laws? Theoria, 47(3), 113–121.

Lewis, D. (1987). Causal decision theory. In Philosophical papers volume II (pp. 306–339). New York: Oxford University Press. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/ebooks/ebc/0195036468. Accessed January 13, 2017.

Listwa, D. (2015). More problematic than the newcomb problems: Extraordinary cases in causal decision theory and belief revision. Retrieved from Columbia University Academic Commons: Columbia University.

Rabinowicz, W. (1982). Two causal decision theories: Lewis vs Sobel. In T. Pauli (Ed.), Philosophical essays dedicated to Lennart Åqvist on his fiftieth birthday. Uppsala: Department of Philosophy.

Rabinowicz, W. (2009). Letters from long ago: On causal decision theory and centered chances. In L.-G. Johansson, J. Österberg & R. Sliwinski (Eds.), Logic, ethics, and all that Jazz—Essays in honour of Jordan Howard Sobel (Vol. 56, pp. 247–273). Uppsala Philosophical Studies. http://lup.lub.lu.se/record/1458836.

Ramsey, F. P. (1931). General propositions and causality. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/194722. Accessed December 15, 2015.

Skyrms, B. (1980). Causal necessity: A pragmatic investigation of the necessity of laws. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sobel, J. H. (1986). Notes on decision theory: Old wine in new bottles. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 64(4), 407–437. doi:10.1080/00048408612342621.

Weirich, P. (2016). Causal decision theory. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2016.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/decision-causal/. Accessed January 12, 2017.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank John Collins for his help with this paper and his years of mentorship. I am also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Listwa, D. The Faulty Signal Problem: counterfactual asymmetries in causal decision theory and rational deliberation. Synthese 195, 2717–2739 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1348-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1348-5