Abstract

Left ventricular assist device (LVAD) support unloads left ventricular (LV) pressure and volume and decreases wall stress. This study investigated the effect of systematic LVAD unloading on the 3-dimensional myocardial wall stress by employing finite element models containing layered fiber structure, active contractility, and passive stiffness. The HeartMate II® (Thoratec, Inc., Pleasanton, CA) was used for LV unloading. The model geometries and hemodynamic conditions for baseline (BL) and LVAD support (LVsupport) were acquired from the Penn State mock circulatory cardiac simulator. Myocardial wall stress of BL was compared with that of LVsupport at 8,000, 9,000, 10,000 RPM, providing mean pump flow (Q mean) of 2.6, 3.2, and 3.7 l/min, respectively. LVAD support was more effective at unloading during diastole as compared to systole. Approximately 40, 50, and 60 % of end-diastolic wall stress reduction were achieved at Q mean of 2.6, 3.2, and 3.7 l/min, respectively, as compared to only a 10 % reduction of end-systolic wall stress at Q mean of 3.7 l/min. In addition, there was a stress concentration during systole at the apex due to the cannulation and reduced boundary motion. This modeling study can be used to further understand optimal unloading, pump control, patient management, and cannula design.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ambardekar AV, Buttrick PM (2011) Reverse remodeling with left ventricular assist devices: a review of clinical, cellular, and molecular effects. Circ Heart Fail 4(2):224–233

Baba HA, Grabellus F, August C, Plenz G, Takeda A, Tjan TD, Schmid C, Deng MC (2000) Reversal of metallothionein expression is different throughout the human myocardium after prolonged left-ventricular mechanical support. J Heart Lung Transplant 19(7):668–674

Barbone A, Oz MC, Burkhoff D, Holmes JW (2001) Normalized diastolic properties after left ventricular assist result from reverse remodeling of chamber geometry. Circulation 104(12 Suppl 1):I229–I232

Bruggink AH, de Jonge N, van Oosterhout MF, Van Wichen DF, de Koning E, Lahpor JR, Kemperman H, Gmelig-Meyling FH, de Weger RA (2006) Brain natriuretic peptide is produced both by cardiomyocytes and cells infiltrating the heart in patients with severe heart failure supported by a left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant 25(2):174–180

Bruggink AH, van Oosterhout MF, de Jonge N, Ivangh B, van Kuik J, Voorbij RH, Cleutjens JP, Gmelig-Meyling FH, de Weger RA (2006) Reverse remodeling of the myocardial extracellular matrix after prolonged left ventricular assist device support follows a biphasic pattern. J Heart Lung Transplant 25(9):1091–1098

Carabello BA (1995) The relationship of left ventricular geometry and hypertrophy to left ventricular function in valvular heart disease. J Heart Valve Dis 4(Suppl 2):S132–S138 (discussion S138–S139)

Chaudhary KW, Rossman EI, Piacentino V 3rd, Kenessey A, Weber C, Gaughan JP, Ojamaa K, Klein I, Bers DM, Houser SR, Margulies KB (2004) Altered myocardial Ca2 + cycling after left ventricular assist device support in the failing human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol 44(4):837–845

Chen Y, Park S, Li Y, Missov E, Hou M, Han X, Hall JL, Miller LW, Bache RJ (2003) Alterations of gene expression in failing myocardium following left ventricular assist device support. Physiol Genomics 14(3):251–260

Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Palmieri V, Okin PM, Boman K, Gerdts E, Nieminen MS, Papademetriou V, Wachtell K, Dahlof B (2000) Left ventricular wall stresses and wall stress-mass-heart rate products in hypertensive patients with electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE study. Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension. J Hypertens 18(8):1129–1138

Drakos SG, Kfoury AG, Selzman CH, Verma DR, Nanas JN, Li DY, Stehlik J (2011) Left ventricular assist device unloading effects on myocardial structure and function: current status of the field and call for action. Curr Opin Cardiol 26(3):245–255

Gere JM, Goodno BJ (2009) Mechanics of materials. Cengage Learning, Mason

Grossman W (1980) Cardiac hypertrophy: useful adaptation or pathologic process? Am J Med 69(4):576–584

Grossman W, Jones D, McLaurin LP (1975) Wall stress and patterns of hypertrophy in the human left ventricle. J Clin Investig 56(1):56–64

Guccione JM, Moonly SM, Wallace AW, Ratcliffe MB (2001) Residual stress produced by ventricular volume reduction surgery has little effect on ventricular function and mechanics: a finite element model study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 122(3):592–599

Heerdt PM, Holmes JW, Cai B, Barbone A, Madigan JD, Reiken S, Lee DL, Oz MC, Marks AR, Burkhoff D (2000) Chronic unloading by left ventricular assist device reverses contractile dysfunction and alters gene expression in end-stage heart failure. Circulation 102(22):2713–2719

Jan KM (1985) Distribution of myocardial stress and its influence on coronary blood flow. J Biomech 18(11):815–820

Jeevanandam V (2012) Are we ready to implant left ventricular assist devices in “less sick” patients? Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 24(1):8–10

Jhun CS, Wenk JF, Zhang Z, Wall ST, Sun K, Sabbah HN, Ratcliffe MB, Guccione JM (2010) Effect of adjustable passive constraint on the failing left ventricle: a finite-element model study. Ann Thorac Surg 89(1):132–137

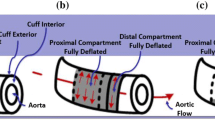

Jhun C-S, Reibson JD, Cysyk JP (2011) Effective ventricular unloading by left ventricular assist device varies with stage of heart failure: cardiac simulator study. ASAIO J 57(5):407–413

Klodell CT Jr, Aranda JM Jr, McGiffin DC, Rayburn BK, Sun B, Abraham WT, Pae WE Jr, Boehmer JP, Klein H, Huth C (2008) Worldwide surgical experience with the Paracor HeartNet cardiac restraint device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 135(1):188–195

La Gerche A, Heidbuchel H, Burns AT, Mooney DJ, Taylor AJ, Pfluger HB, Inder WJ, Macisaac AI, Prior DL (2011) Disproportionate exercise load and remodeling of the athlete’s right ventricle. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43(6):974–981

Mann DL, Kubo SH, Sabbah HN, Starling RC, Jessup M, Oh JK, Acker MA (2011) Beneficial effects of the CorCap cardiac support device: Five-year results from the Acorn Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 143(5):1036–1042

Martina JR, Schipper ME, de Jonge N, Ramjankhan F, de Weger RA, Lahpor JR, Vink A (2013) Analysis of aortic valve commissural fusion after support with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg 17(4):616–624

Morgan JA, Brewer RJ, Nemeh HW, Henry SE, Neha N, Williams CT, Lanfear DE, Tita C, Paone G (2012) Management of aortic valve insufficiency in patients supported by long-term continuous flow left ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg 94(5):1710–1712

Mueller XM, Tevaearai HT, Tucker O, Boone Y, von Segesser LK (2001) Reshaping the remodelled left ventricle: a new concept. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 20(4):786–791

Mueller XM, Tevaearai H, Boone Y, Augstburger M, von Segesser LK (2002) An alternative to left ventricular volume reduction. J Heart Lung Transplant 21(7):791–796

Remmelink M, Sjauw KD, Henriques JP, de Winter RJ, Vis MM, Koch KT, Paulus WJ, de Mol BA, Tijssen JG, Piek JJ, Baan J Jr (2010) Effects of mechanical left ventricular unloading by Impella on left ventricular dynamics in high-risk and primary percutaneous coronary intervention patients. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 75(2):187–194

Saraf H, Ramesh KT, Lennon AM, Merkle AC, Roberts JC (2007) Mechanical properties of soft human tissues under dynamic loading. J Biomech 40(9):1960–1967

Sheikh FH, Russell SD (2011) HeartMate(R) II continuous-flow left ventricular assist system. Expert Rev Med Devices 8(1):11–21

Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, Rogers JG, Miller LW, Sun B, Russell SD, Starling RC, Chen L, Boyle AJ, Chillcott S, Adamson RM, Blood MS, Camacho MT, Idrissi KA, Petty M, Sobieski M, Wright S, Myers TJ, Farrar DJ (2010) Clinical management of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 29(4 Suppl):S1–S39

Smalling RW, Cassidy DB, Barrett R, Lachterman B, Felli P, Amirian J (1992) Improved regional myocardial blood flow, left ventricular unloading, and infarct salvage using an axial-flow, transvalvular left ventricular assist device. A comparison with intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation and reperfusion alone in a canine infarction model. Circulation 85(3):1152–1159

Streeter DD Jr, Hanna WT (1973) Engineering mechanics for successive states in canine left ventricular myocardium. I. Cavity and wall geometry. Circ Res 33(6):639–655

Streeter DD Jr, Hanna WT (1973) Engineering mechanics for successive states in canine left ventricular myocardium. II. Fiber angle and sarcomere length. Circ Res 33(6):656–664

Sun K, Stander N, Jhun CS, Zhang Z, Suzuki T, Wang GY, Saeed M, Wallace AW, Tseng EE, Baker AJ, Saloner D, Einstein DR, Ratcliffe MB, Guccione JM (2009) A computationally efficient formal optimization of regional myocardial contractility in a sheep with left ventricular aneurysm. J Biomech Eng 131(11):111001

Veress AI, Segars WP, Tsui BM, Gullberg GT (2011) Incorporation of a left ventricle finite element model defining infarction into the XCAT imaging phantom. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 30(4):915–927

Walsh RG (2005) Design and features of the acorn corcap cardiac support device: the concept of passive mechanical diastolic support. Heart Fail Rev 10(2):101–107

Wohlschlaeger J, Schmitz KJ, Schmid C, Schmid KW, Keul P, Takeda A, Weis S, Levkau B, Baba HA (2005) Reverse remodeling following insertion of left ventricular assist devices (LVAD): a review of the morphological and molecular changes. Cardiovasc Res 68(3):376–386

Zafeiridis A, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB (1998) Regression of cellular hypertrophy after left ventricular assist device support. Circulation 98(7):656–662

Zhang J, Narula J (2004) Molecular biology of myocardial recovery. Surg Clin North Am 84(1):223–242

Zhang Z, Tendulkar A, Sun K, Saloner DA, Wallace AW, Ge L, Guccione JM, Ratcliffe MB (2011) Comparison of the young-Laplace law and finite element based calculation of ventricular wall stress: implications for post infarct and surgical ventricular remodeling. Ann Thorac Surg 91(1):150–156

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Constitutive equations for myocardium

1.1.1 Diastolic material properties

Diastolic material properties are represented by the strain energy function, W, to describe the myocardium with respect to the local muscle fiber direction as,

where the material constant C controls the myocardial stiffness, and material constants b f , b t , and b fs govern the degree of anisotropy. E 11 is fiber strain, E 22 is cross-fiber strain, E 33 is radial strain, E 23 is shear strain in the transverse plane, and E 12 and E 13 are shear strain in the fiber-cross fiber and fiber-radial planes [34].

1.1.2 Systolic material properties

Systolic material properties are determined by defining the stress components referred to fiber coordinates. The systolic fiber stress is described as the sum of the passive stress components derived from the strain energy function W and an active fiber-direction component, T 0 , that is a function of time, t, peak intracellular calcium concentration, Ca 0 , sarcomere length, l, and the maximum isometric tension, T max [34],

\(\tilde{S}\) is the second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor, p is a Lagrange multiplier introducing the incompressibility constraint, and the value was adopted from the bulk modulus of heart tissue [28], J is the Jacobian of the deformation gradient tensor \(\tilde{F}\), \(\tilde{C}\) is the right Cauchy-Green deformation tensor, and W is the strain energy function in Eq. (1). A time-varying elastance model at end-systole is given by

T max is the maximum isometric tension achieved at the longest sarcomere length and maximum peak intracellular calcium concentration, (Ca 0 )max, and C t is given by

where m and b are constants. The length-dependent calcium sensitivity is given by

where B is constant, l 0 is the sarcomere length at which no active tension develops, and l R is the stress-free sarcomere length. Finally, the Cauchy stress tensor used to calculate myocardial fiber stress is given by

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jhun, CS., Sun, K. & Cysyk, J.P. Continuous flow left ventricular pump support and its effect on regional left ventricular wall stress: finite element analysis study. Med Biol Eng Comput 52, 1031–1040 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-014-1205-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-014-1205-3