Abstract

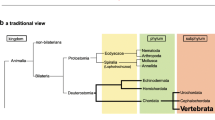

The concept of chordates arose from the alliance between embryology and evolution in the second half of the nineteenth century, as a result of a theoretical elaboration on Kowalevsky’s discoveries about some fundamental similarities between the ontogeny of the lancelet, a putative primitive fish, and that of ascidians, then classified as molluscs. Carrying out his embryological studies in the light of Darwin’s theory and von Baer’s account of the germ layers, Kowalevsky was influenced by the German tradition of idealistic morphology that was concerned with transformations driven by laws of form, rather than with a gradual evolution occurring by means of variation, selection and adaptation. In agreement with this tradition, Kowalevsky interpreted the vertebrate-like structures of the ascidian larva according to von Kölliker’s model of heterogeneous generation. Then, he asserted the homology of the germ layers and their derivatives in different types of animals and suggested a common descent of annelids and vertebrates, in agreement with Saint-Hilaire’s hypothesis of the unity of composition of body plans, but in contrast with Haeckel’s idea of the Chordonia (chordates). In The Descent of Man Darwin quoted Kowalevsky’s discoveries, but accepted Haeckel’s interpretation of the ascidian embryology within the frame of a monophyletic tree of life that was produced by the fundamental biogenetic law. Joining embryology to evolution in the light of idealistic morphology, the biogenetic law turned out to be instrumental in bringing forth different evolutionary hypotheses: it was used by Haeckel and Darwin to link vertebrates to invertebrates by means of the concept of chordates, and by Kowalevsky to corroborate the annelid theory of the origin of vertebrates. Yet, there was still another interpretation of Kowalevsky’s discoveries. As an adherent to empiricism and to Cuvier’s theory of types, von Baer asserted that these discoveries did not prove convincingly a dorsal position of the nervous system in the ascidian tadpole larva; hence, they could not support a homology between different animal types suggesting a kinship between ascidians and vertebrates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

French original: “Il y a eu littéralement, de 1870 à 1900, une débauche, parfois même un délire de phylogénie, dont la responsabilité remonte surtout à Haeckel”.

French original: “Le système nerveux est, au fond, tout l’animal; les autres systèmes ne sont là que pour l’entretenir et le servir”. Annales du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle 19, 1812, p 76.

In: Heuss T (1991) Anton Dohrn. A life for science. Springer, Berlin, pp 179–180.

German original: “So wandelt eine solche unwissenschaftliche Vergleichung wie in einem Labyrinthe, in dem an den ersten Irrweg nur neue sich anreihen”.

French original: “Je n’aurais pas parlé ici de ces conceptions, si elles étaient restées dans le domaine de ces théories abstraites dont on nous a gratifiés à foison depuis un certain temps et qui trouveront leur fin comme la défunte philosophie de la nature. Mais on se heurte à chaque pas à ces divagations; et elles se mêlent, chez certains auteurs, tellement avec les faits observés, qu’il est souvent difficile de démêler les éléments de la mixture qu’on vous offre. Il y a en outre un danger sérieux…”. Sur un nouveau genre de Médusaire sessile, Lipkea ruspoliana (C.V.), 1887, p 37, quoted by de Quatrefages (1894), p 119

German original: “Die wichtigsten Wahreiten in den Naturwissenschaften sind wederallein durch Zergliederung der Begriffe der Philosophie, noch allein durch blösses Erfahren gefunden worden, sondern durch eine denkende Erfahrung welche das Wesentliche von dem Zenfälligen unterscheidet, und dadurch Grundsätze findet, aus welchen viele Erfahrungen abgeleitet werden. Dies ist mehr als blösses Erfahren, und wen Man will, eine philosophische Erfahrung”. Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen für Vorlesungen. Vol 2, p 522.

Contrary to Kowalevsky’s description, only in echinoderms the blastopore becomes the anus, in Phoronis, in particular, it closes towards anterior and its residual opening gives rise to the mouth.

As reported by primary and secondary scientific literature (e.g. Willey 1893; Dawydoff 1928; Brien 1948), Kowalevsky described the primordia of the branchial atria of ascidians as if they took their origin from two ectodermal invaginations. However, according to Kowalevsky the atrial cavities arise at first as evaginating pouches of the anterior gut. In his paper on Perophora listeri (Kowalevsky 1870a, translated from Russian by A. Giard 1874) he said: “…on voit qu’il est possible de comparer entre elles, et même de considérer comme parties homologues, la cavité du corps des Échinodermes et la cavité cloacale des Ascidies. Chez les Ascidies, il y aurait donc, pendant toute la vie, deux sortes de cavités, dont l’une, provenant de la cavité de segmentation, répondrait à la fentre qu’on remarque chez la Sagitta entre le feuillet externe et le feuillet interne; l’autre, la cavité cloacale, serait l’homologue de la cavité du corps de la Sagitta, des Échinodermes et de certains autres animaux”. In a similar way, in his paper on Ciona (Ascidia) intestinalis (1871a) Kowalevsky asserted that the greatest part of the branchial atria was endodermal, while the two ectodermal invaginations gave rise to the rudiment of the cloacal siphon: “Es bleibt uns noch jetzt zu erklären, welchen Antheil die Einstülpungen an der Bildung der Kiemenspalten nehmen… Man beobachtet an diesem Stadium, dass der obere Theil des Vorderdarms sich an beiden Seiten als zwei Falten erhebt, welche bald so gross werden, dass sie einen Theil der Gehirnblase von den Seiten bedecken und ihr hinteres Ende (Fig. 34, Tafel XII) jederseits dicht an die durch Einstülpung entstandene Kloake stösst”.

German original: “Dagegen möchte ich anführen, dass, wenn wir z. B. die Wirbelthiere, als einen überhaupt hoch organisirten Typus, von einem Urvater ableiten, der zu den niedrig stehenden Typen der Thiere gehörte z. B. zu den Mollusken (vielleicht Tunicaten) oder Würmern (z. B. Sagitta oder ähnlichen) so wären doch die Keimblätter der zuerst entstandenen Wirbelthiere mit denjenigen der anderen Typen zu vergleichen, und wenn wir die Keimblätter des Amphioxus mit denjenigen der Würmer und Mollusken vergleichen, so müssen wir dies mit den Keimblättern auch der anderen Wirbelthiere machen”.

Kowalevsky ended this paper by the following sentence: “Aus allen diesen Gründen halte ich die Ansicht, dass die Organe der Thiere verschiedener Typen nicht homolog sein könnten, für nich haltbar”.

German original: “Wenn eine solche Annahme auch sehr befremdend erscheint, so stimmt sie doch mit der jetzt herrschenden Anschauung, dass embryonale Bildungen, embryonale Stadien wirklich existirende Formen darstellen”.

German original: “Wenn Claparède noch zweifelt, ob diese Fasern doch noch vielleicht als Nervenfasern anzusehen sind, so ist ihre Entwicklung aus dem mittleren Blatte ein so wichtiger Grund gegen ihre Nervennatur, dass ich dieselben keineswegs für Nervenfasern ansehen kann”. (Kowalevsky 1871a, p 123).

In Darwin’s words: “If this work had appeared before my essay had been written, I should probably never have completed it. Almost all the conclusions at which I arrived I find confirmed by this naturalist, whose knowledge on many points is much fuller than mine. Wherever I have added any fact or view from Prof. Haeckel’s writings, I give his authority in the text; other statements I leave as they originally stood in my manuscript, occasionally giving in the foot-notes references to his work, as a confirmation of the more doubtful or interesting points”.

In The life and letters of Charles Darwin, vol 3, p 180.

In The life and letters of Charles Darwin, vol. 3, p 198. The year of this letter is uncertain and is reported as (1875?).

This account of Michael Foster was included in an anonymous review article: The kinship of Ascidians and Vertebrates. Q J Microsc Sci 10:59–69, 1870. It seems quite possible that the author of the review was Edwin Ray Lankester, the editor of the journal.

Evidently, von Baer was following the chordate affair with close attention, since he said that the paper of Dönitz, first expected from July 1870, was likely to be issued in late 1871, being included at the end of the 1870 volume of the Archiv für Anatomie und Physiologie. An English translation of the paper of Dönitz was published in 1871 in a review article, Q J Microsc Sci 9:281–283.

German original: “Müssen wir nicht hierin ein allgemeines Gesetz der bildenden Natur vermuthen?”.

Unlike Kowalevsky, Kupffer (1870) noticed the unusual dorsal position of the mouth in the ascidian larva, but he considered this detail to be of minor importance as compared to the vertebrate-like organization of the body. To account for this peculiarity, he suggested that the development of the adhesive papillae could shift the mouth to the dorsal side.

German original: “Der Lehre von der Transmutation der Thierformen principiell nicht abgeneigt, sondern eher zugeneigt, verlange ich doch vollständigen Beweiss, bevor ich an eine Umwandlung des Wirbelthier-Typus in den der Mollusken glauben kann”.

German original: “Man darf nun wohl vermuthen, dass überhaupt der Stoff für die Bildung der Centraltheile des Nervensystems aus der äussern Schicht der ersten Anlage des Embryos genommen wird und durch Einfaltung die ihm gebührende Stelle erhält, und dass diesem allgemeinen Gesetze gemäss auch das Nervencentrum der Tunicaten durch Einfaltung aus der äussern Embryonal-Schicht entsteht”.

The paper of Kowalevsky Embryologische Studien an Würmern und Arthropoden was submitted to the Physico-Mathematical Class of the Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg on 18 November 1869 and published in 1871. Although he dissented from his conclusion, von Baer gave his positive vote to Kowalevsky also on occasion of the first von Baer-Prize in 1867, when the award was made to Kowalevsky for his study of ascidian development.

Kowalevsky (1871a) replied to Metschnikoff on several points concerning, in particular, the fate of the blastopore and the germ layer derivation of notochord and nervous system, but he never discussed the problem of orientation.

German original: “Ich hatte dabei die vielen Dilettanten im Auge, die an vollständige Transmutationen glauben, und die geneigt sein werden, es für blosse Eitelkeit zu halten, wenn man in den Ascidien nicht die Vorfahren der Menschen erkennen will”.

In his treatise on embryology (1828) von Baer said that if it were a bird writing such a volume in the light of the theory of transmutation, he would note that adult humans resemble embryonic birds. Just as the latter, humans lack beaks, have anterior and posterior limbs which are similar to each other, and moreover, they show tiny hairs which correspond to the most primitive form of feather production. As a conclusion, birds are higher forms which evolved from humans.

“Of late the attempt to arrange genealogical trees involving hypothetical groups has come to be the subject of some ridicule, perhaps deserved. But since this is what modern morphological criticism in great measure aims at doing, it cannot be altogether profitless to follow this method to its logical conclusions. That the results of such criticism must be highly speculative, and often liable to grave error, is evident”. In: The ancestry of the Chordata. Q J Microsc Sci 26, p 535–536.

Dealing with the problem of the origin of the notochordal cells of the lancelet Thomas H. Morgan wrote: “There has been much discussion as to whether these cells are to be called ectoderm or endoderm, but this discussion has lost interest since we have come to pay more attention to the cell-lineage of the embryo than to phylogenetic questions based on imaginary two-layered ancestors of those stages”. In: Experimental embryology, 1927, p 322.

Giard (1874) held that the kinship between ascidians and vertebrates shown by their developmental similarities was not so close as many people believed. French original: “Mais cette parenté est moins directe qu’on ne l’a supposé, et les points communs que l’on retrouve chez l’adulte indiquent bien moins une filiation qu’une certaine capacité à produire des formations de même nature, mais non synchrones, capacité qui est évidemment l’héritage d’un ancêtre éloigné commun”.

According to Carazzi (1906) “the vertebrates are to be considered separately from the lancelet from the embryological as well as the anatomical point of view… Even if we agree to use the inclusive term chordates for indicating tunicates, lancelets and vertebrates, we must take into account that tunicates and cephalochordates share a number of characters, but they differ widely from the vertebrates. This conclusion implies that the phylum Vertebrata is completely separated from all phyla of invertebrates”.

This ironic comment is taken from the scientific blog Pharyngula, run by P. Z. Myers and hosted on ScienceBlogs.com.

References

Appel TA (1987) The Cuvier–Geoffroy debate: French biology in the decades before Darwin. Oxford University Press, New York

Arendt D, Nübler-Jung K (1997) Dorsal or ventral: similarities in fate maps and gastrulation patterns in annelids, arthropods and chordates. Mech Dev 61:7–21

Bateson W (1886) The ancestry of the Chordata. Q J Microsc Sci 26:535–571

Bowler PJ (1990) Charles Darwin: the man and his influence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bowler PJ (1996) Life’s splendid drama. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Brien P (1948) Embranchement des Tuniciers. In: Traité de Zoologie, directed by Pierre-P. Grassé, Masson, Paris, pp 553–930

Carazzi D (1906) L’embriologia dell’Aplysia ed i problemi fondamentali dell’embriologia comparata. Arch Ital Anat Embriol 5:667–709

Cerfontaine P (1906) Recherches sur le développement de l’Amphioxus. Arch Biol 22:229–418 pls XII–XXII

Claparède E (1869) Histologische Untersuchungen über den Regenwurm (Lumbricus terrestris Linné). Z Wiss Zool 19:563–624 pls XLIII–XLVIII

Cuvier G (1812) Sur un nouveau rapprochement à établir entre les classes qui composent le règne animal. Ann Mus Hist Nat 19:73–84

Darwin CR (1859) On the origin of species by means of natural selection or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. Murray, London

Darwin CR (1871) The descent of man and selection in relation to sex, 1st edn. Murray, London

Darwin CR (1872) The expression of the emotions in man and animals. Murray, London

Darwin CR (1874) The descent of man and selection in relation to sex, 2nd edn. Murray, London

Darwin CR (1887) The life and letters of Charles Darwin. In: Darwin F (ed), vol 3. Murray, London

Davidson EH, Peterson KJ, Cameron RA (1995) Origin of bilaterian body plans: evolution of developmental regulatory mechanisms. Science 270:1319–1325

Dawydoff C (1928) Traité d’embryologie comparée des invertébrés. Masson, Paris

De Quatrefages A (1845) Mémoire sur le système nerveux et sur l’histologie du Branchiostome ou Amphioxus. Ann Sci Natur 4, 3e série, Zoologie 197–248

De Quatrefages A (1894) Haeckel. In: Les émules de Darwin vol II. Alcan, Paris, pp 53–132

De Selys Longchamps M (1902) Recherches sur le développement de Phoronis. Arch Biol 18:495–597

Delsman HC (1922) The ancestry of vertebrates. Weltervreden, Java: Visser & Co., and Amersfoort, Holland

Denes AS, Jékely G, Steinmetz PRH, Raible F, Snyman H, Prud’homme B, Ferrier DEK, Balavoine G, Arendt D (2007) Molecular architecture of annelid nerve cord supports common origin of nervous system centralization in Bilateria. Cell 129:277–288

Dohrn A (1875) Der Ursprung der Wirbelthiere und das Princip des Functionswechsels: Genealogische Skizzen. Engelmann, Leipzig

Dönitz W (1871a) Über die sogenannte Chorda der Ascidienlarven und die vermeintliche Verwandschaft von Wirbellosen und Wirbelthiere. Arch Anat Physiol 1870:761–764

Dönitz W (1871b) On the so-called chorda of the ascidian larvae, and the alleged affinity of the invertebrate and vertebrate animals. Q J Microsc Sci 9:281–283 (review)

Drach P (1948) La notion de Procordé et les embranchements de Cordés. In: Traité de Zoologie, directed by Pierre-P. Grassé, vol XI. Masson, Paris, pp 545–551

Gegenbaur C (1875) Die Stellung und Bedeutung der Morphologie. Morphol Jahrb 1:1–19

Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire É (1833) Mémoire sur l’oreille osseuse des crocodiles et des téléosaures. Mem Acad Royale Sci Inst France 12:93–139

Giard A (1874) L’embryogénie des Ascidies et l’origine des Vertébrés, Kowalevsky et Baer. Rev Sci Ser II 4:25–35

Giard A (1904) Controverses transformistes. Naud, Paris

Haeckel E (1866) Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Reimer, Berlin

Haeckel E (1868) Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte. Reimer, Berlin

Haeckel E (1872) Die Kalkschwämme. Eine Monographie. Reimer, Berlin

Haeckel E (1874a) The gastraea-theory, the phylogenetic classification of the animal kingdom and the homology of the germ-lamellae. Q J Microsc Sci 14:142–165

Haeckel E (1874b) Anthropogenie oder Entwicklungsgeschichte des Menschen. Keimes- und Stammesgeschichte. Engelmann, Leipzig

Haeckel E (1879) The evolution of man: a popular exposition of the principal points of human ontogeny and phylogeny. Appleton, New York

Haeckel E (1899) Die Welträtsel Studien über monistische Philosophie. Strauss, Bonn

Hatschek B (1878) Studien über Entwicklungsgeschichte der Anneliden: Ein Beitrag zur Morphologie der Bilateren. Arb Zool Inst Wien 1:1–128

Holland LZ, Holland ND (2007) A revised fate map for amphioxus and the evolution of axial patterning in chordates. Integr Comp Biol 47:360–372

Ivanova-Kazas OM (1992) Baer’s law of ontogenic divergence. Ontogenez (Russ J Dev Biol) 23:175–179 (in Russian)

Kowalevsky AO (1865) Developmental history of the lancelet (Amphioxus lanceolatus). Thesis, St. Petersburg (in Russian)

Kowalevsky AO (1866) Entwicklungsgeschichte der einfachen Ascidien. Mém Acad Imp Sci St. Pétersbourg, Ser. VII, 10:1–19 pls I–III

Kowalevsky AO (1867) Entwicklungsgeschichte des Amphioxus lanceolatus. Mem Acad Imp Sci St. Pétersbourg, Ser VII, 11:1–17 pls I–III

Kowalevsky AO (1870a) On the budding of Perophora listeri Wiegm. Zapiski Kiew Gesell Naturforsch 1 (3) (in Russian) (Translated by Giard 1874 Sur le bourgeonnement du Perophora listeri Wiegm. Rev Sci Nat Montpell 3:213–235 pls V–VII)

Kowalevsky AO (1870b) On the developmental history of Amphioxus lanceolatus. Zapiski Kiew Gesell Naturforsch 1:327–338, pl XV (in Russian)

Kowalevsky AO (1871a) Weitere Studien über die Entwicklung der einfachen Ascidien. Arch Mikrosk Anat 7:101–129 pls X–XIII

Kowalevsky AO (1871b) Embryologische Studien an Würmern und Arthropoden. Mem Acad Imp Sci St. Pétersbourg, Ser VII, 16:1–70 pls I–XII

Kowalevsky AO (1877) Weitere Studien über die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Amphioxus lanceolatus, nebst einem Beitrage zur Homologie des Nervensystems der Würmer und Wirbelthiere. Arch Mikrosk Anat 13:181–204 pls XV–XVI

Lankester ER (1880) Degeneration: a chapter in Darwinism. Macmillan, London

Lankester ER, Willey A (1890) The development of the atrial chamber of Amphioxus. Q J Microsc Sci 31:445–466 pls XXIX–XXXII

Lenoir T (1982) The strategy of life: teleology and mechanics in nineteenth-century German biology. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Levit GS (2007) The roots of Evo-Devo in Russia: is there a characteristic “Russian Tradition”? Theory Biosci 126:131–148

Metschnikoff I (1869a) Über die Systematische Stellung von Balanoglossus. Zool Anz 4:139–143, 153–157

Metschnikoff I (1869b) Entwickelungsgeschichtliche Beiträge. Bull Acad Imp Sci St. Pétersbourg 13:284–300 pls I–IV

Metschnikoff I (1870) Untersuchungen über die Metamorphose einiger Seethiere. Über Tornaria. Z Wiss Zool 20:131–144

Milne-Edwards H (1857) Leçons de physiologie et d’anatomie comparées de l’homme et des animaux faites à la Faculté des Sciences. Masson, Paris

Minot CS (1897) Cephalic homologies: a contribution to the determination of the ancestry of vertebrates. Am Nat 31:927–943

Morgan TH (1890) On the amphibian blastopore. Stud Biol Labor John Hopkins Univ Baltimore 4:355–377 pls XL–XLII

Morgan TH (1927) Experimental embryology. Columbia University Press, New York

Müller J (1833) Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen für Vorlesungen. Hölscher, Coblenz

Müller F (1864) Für Darwin. Engelmann, Leipzig

Neal HV, Rand HW (1936) Comparative anatomy. Blakiston’s Son & Co., Philadelphia

Nielsen C (1985) Animal phylogeny in the light of the trochaea theory. Biol J Linn Soc 25:243–299

Nielsen C (1991) The development of the brachiopod Crania (Neocrania) anomala (O. F. Müller) and its phylogenetic significance. Acta Zool 72:7–28

Nielsen C, Nørrevang A (1985) The trochaea theory: an example of life cycle phylogeny. In: Conway Morris S, George JD, Gibson R, Platt HM (eds) The origin and relationships of lower invertebrate groups. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 28–41

Nishida H (2005) Specification of embryonic axis and mosaic development in ascidians. Dev Dyn 233:1177–1193

Nyhart LK (1995) Biology takes form: animal morphology and the German universities 1800–1900. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Ospovat D (1981) The development of Darwin’s theory: natural history, natural theology, and natural selection, 1838–1859. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Owen R (1848) On the archetype and homologies of the vertebrate skeleton. Van Voorst, London

Perrier E (1884) La philosophie zoologique avant Darwin. Alcan, Paris

Peterson KJ, Cameron RA, Davidson EH (1997) Set-aside cells in maximal indirect development: evolutionary and developmental significance. Bioessays 19:623–631

Raineri M (1998) Proposta di una nuova classificazione di Tunicati e Cefalocordati come Gastroneuralia. Implicazioni filogenetiche e cenni storici sulle origini del concetto di Procordati. Ann Mus Civ St Nat “G. Doria” 92:1–83

Raineri M (2006) Are protochordates chordates? Biol J Linn Soc 87:261–284

Raineri M (2008) Old and new concepts in Evo-Devo. In: Pontarotti P (ed) Evolutionary biology from concept to application. Springer, Berlin, pp 95–114

Rattenbury JC (1954) The embryology of Phoronopsis viridis. J Morphol 95:289–349

Sedgwick A (1884) The origin of metameric segmentation. Q J Microsc Sci 24:43–82

Seeliger O (1893) Über die Entstehung des Peribranchialraumes in den Embryonen der Ascidien. Z Wiss Zool 56:365–401 pls XIX–XX

Semper C (1875) Die Stammesverwandtschaft der Wirbelthiere und Wirbellosen. Arb Zool Inst Würzburg 2:25–76

Semper C (1876) Die Verwandtschaftsbeziehungen der gegliederten Thiere. Arb Zool Inst Würzburg 3:9–404

Serres AÉ (1842) Précis d’anatomie transcendante appliquée à la physiologie. Gosselin, Paris

Serres AÉ (1860) Principes d’embryogénie, de zoogénie et de tératogénie. Mem Acad Royale Sci Inst France 25 pp XV + 943

Vogt C (1887) Sur un nouveau genre de médusaire sessile, Lipkea ruspoliana (C.V.), p 37, quoted by de Quatrepages (1894), p 119

von Baer KE (1828) Über Entwicklungsgeschichte der Thiere. Beobachtung und Reflexion. Erster Theil. Bornträger, Königsberg

von Baer KE (1873) Entwickelt sich die Larve der einfachen Ascidien in der ersten Zeit nach dem Typus der Wirbelthiere? Mem Acad Imp Sci St. Pétersbourg, Ser VII 19:1–35 pl I

von Baer KE (1876) Über Darwin’s Lehre. In: Reden, gehalten in wissenschaftlichen Versammlungen und kleinere Aufsätze vermischten Inhalts. Zweiter Theil. Schmitzdorff, St. Pétersbourg, pp 235–480

von Kölliker A (1864) Über die Darwin’sche Schöpfungstheorie. Zeit Wiss Zool 14:174–186

von Kupffer C (1869) Die Stammverwandtschaft zwischen Ascidien und Wirbelthieren. Briefliche Mittheilung an den Herausgeber. Archiv Mikrosk Anat 5:459–463

von Kupffer C (1870) Die Stammverwandtschaft zwischen Ascidien und Wirbelthieren. Nach Untersuchungen über die Entwicklung der Ascidia canina (Zool Dan). Archiv Mikrosk Anat 6:115–172 pls VIII–X

von Leydig F (1864) Vom Baue des thierischen Körpers: Handbuch der vergleichenden Anatomie. Laupp, Tübingen

Willey A (1893) Studies on the Protochordata I. On the origin of the branchial stigmata, preoral lobe, endostyle, atrial cavities, & c., in Ciona intestinalis, Linn., with remarks on Clavelina lepadiformis. Q J Microsc Sci 34:317–360 pls XXX–XXXI

Ziegler HE (1902) Lehrbuch der vergleichenden Entwickelungsgeschichte der niederen Wirbeltiere. Verlag von Gustav Fischer, Jena

Acknowledgments

The enduring support of the libraries of the “Anton Dohrn” Zoological Station of Naples and the Museum of Natural History “G. Doria” of Genoa is acknowledged with thanks.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raineri, M. On some historical and theoretical foundations of the concept of chordates. Theory Biosci. 128, 53–73 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12064-009-0059-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12064-009-0059-y