Abstract

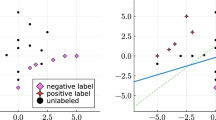

Binary classification tasks are among the most important ones in the field of machine learning. One prominent approach to address such tasks are support vector machines which aim at finding a hyperplane separating two classes well such that the induced distance between the hyperplane and the patterns is maximized. In general, sufficient labeled data is needed for such classification settings to obtain reasonable models. However, labeled data is often rare in real-world learning scenarios while unlabeled data can be obtained easily. For this reason, the concept of support vector machines has also been extended to semi- and unsupervised settings: in the unsupervised case, one aims at finding a partition of the data into two classes such that a subsequent application of a support vector machine leads to the best overall result. Similarly, given both a labeled and an unlabeled part, semi-supervised support vector machines favor decision hyperplanes that lie in a low density area induced by the unlabeled training patterns, while still considering the labeled part of the data. The associated optimization problems for both the semi- and unsupervised case, however, are of combinatorial nature and, hence, difficult to solve. In this work, we present efficient implementations of simple local search strategies for (variants of) the both cases that are based on matrix update schemes for the intermediate candidate solutions. We evaluate the performances of the resulting approaches on a variety of artificial and real-world data sets. The results indicate that our approaches can successfully incorporate unlabeled data. (The unsupervised case was originally proposed by Gieseke F, Pahikkala et al. (2009). The derivations presented in this work are new and comprehend the old ones (for the unsupervised setting) as a special case.)

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Notes

For the sake of simplicity, the offset set \({b \in {\mathbb R}}\) is omitted in the latter formulation. From both a theoretical as well as a practical point of view, the additional term does not yield any known advantages for kernel functions like the RBF kernel [25, 30]. However, for the linear kernel, the offset term can make a difference since it addresses translated data. In case such an offset effect is needed for a particular learning task, one can add a dimension of ones to the input data to obtain a (regularized) offset term [25].

The random generation of an initial candidate solution takes the class ratio given by the balance constraint into account, i.e., for an initial candidate solution y we have y i = 1 with probability b c and y i = − 1 with probability 1 − b c for \(i = l+1,\ldots, n. \)

If K is invertible, then

$$ \begin{aligned} - 2 {({\bf D} {\bf K})}^{\rm T}({\bf D} {\bf y}-{\bf D} {\bf K} {\bf c}) + 2 \lambda {\bf K} {\bf c} &= {\bf 0} \\ \Leftrightarrow {({\bf D} {\bf K})}^{\rm T} ({{\bf D} {\bf K}{\bf D}} + \lambda {\bf I}) {\bf D}^{-1}{\bf c} &= {({\bf D} {\bf K})}^{\rm T} {\bf D} {\bf y} \\ \Leftrightarrow {\bf c} &= {\bf D} {\bf G} {\bf D} {\bf y} \\ \end{aligned} $$If K is not invertible, then the latter equation can be used as well since we only need a single solution (if c = D G D y, then (D K)T G −1 D −1 c = (D K)T D y holds as well).

As mentioned, various other update schemes are possible. Another update scheme, for instance, consists in updating the terms in (10) individually, i.e., to handle the first term by updating the vector D K c * = D K D G D y and therefore (D y − D K c *)T (D y − D K c *) in linear time. Similarly, the second term can be handled in linear time (by first updating K c * = K D G D y separately). Note that one can also consider one of the predecessors of Eq. (13).

Naturally, in case a too small subset is selected, the performance of the final model can be bad.

Similar data sets are often used in related experimental evaluations, see, e.g., [8]

For instance, [8] propose to make use of the test set to select the model parameters: “This allowed for finding hyperparameter values by minimizing the test error, which is not possible in real applications; however, the results of this procedure can be useful to judge the potential of a method. To obtain results that are indicative of real world performance, the model selection has to be performed using only the small set of labeled points.”

As a side note, we would like to point out that this special type shows a very similar behavior with respect to the classification performance compared to the more general setup with μ = 5 and ν = 25 (if sufficient restarts are performed).

References

Bennett KP, Demiriz A (1998) Semi-supervised support vector machines. In: Kearns MJ, Solla SA, Cohn DA (eds) Advances in neural information processing systems 11, MIT Press, pp 368–374

Beyer HG, Schwefel HP (2002) Evolution strategies—a comprehensive introduction. Nat Comput 1:3–52

Bie TD, Cristianini N (2003) Convex methods for transduction. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 16, MIT Press, pp 73–80

Boyd S, Vandenberghe L (2004) Convex optimization. Cambridge University Press, New York

Chang CC, Lin CJ (2001) LIBSVM: a library for support vector machines. Software available at http://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/~cjlin/libsvm

Chapelle O, Zien A (2005) Semi-supervised classification by low density separation. In: Proceedings of the tenth international workshop on artificial intelligence and statistics, pp 57–64

Chapelle O, Chi M, Zien A (2006) A continuation method for semi-supervised svms. In: Proceedings of the international conference on machine learning, pp 185–192

Chapelle, O, Schölkopf, B, Zien, A (eds) (2006) Semi-supervised learning. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Chapelle O, Sindhwani V, Keerthi SS (2008) Optimization techniques for semi-supervised support vector machines. J Mach Learn Res 9:203–233

Collobert R, Sinz F, Weston J, Bottou L (2006) Trading convexity for scalability. In: Proceedings of the international conference on machine learning, pp 201–208

Droste S, Jansen T, Wegener I (2002) On the analysis of the (1+1) evolutionary algorithm. Theor Comput Sci 276(1–2):51–81

Evgeniou T, Pontil M, Poggio T (2000) Regularization networks and support vector machines. Adv Comput Math 13(1):1–50, http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1018946025316

Fogel DB (1966) Artificial intelligence through simulated evolution. Wiley, New York

Fung G, Mangasarian OL (2001) Semi-supervised support vector machines for unlabeled data classification. Optim Methods Softw 15:29–44

Gieseke F, Pahikkala T, Kramer O (2009) Fast evolutionary maximum margin clustering. In: Proceedings of the international conference on machine learning, pp 361–368

Golub GH, Van Loan C (1989) Matrix computations, 2nd edn. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London

Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J (2009) The elements of statistical learning. Springer, New York

Holland JH (1975) Adaptation in natural and artificial systems. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Horn R, Johnson CR (1985) Matrix analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Joachims T (1999) Transductive inference for text classification using support vector machines. In: Proceedings of the international conference on machine learning, pp 200–209

Mierswa I (2009) Non-convex and multi-objective optimization in data mining. PhD thesis, Technische Universität Dortmund

Nene S, Nayar S, Murase H (1996) Columbia object image library (coil-100). Tech. rep

Rechenberg I (1973) Evolutionsstrategie: optimierung technischer systeme nach prinzipien der biologischen evolution. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart

Rifkin R, Yeo G, Poggio T (2003) Regularized least-squares classification. In: Advances in learning theory: methods, models and applications, IOS Press, pp 131–154

Rifkin RM (2002) Everything old is new again: a fresh look at historical approaches in machine learning. PhD thesis, MIT

Schölkopf B, Herbrich R, Smola AJ (2001) A generalized representer theorem. In: Proceedings of the 14th annual conference on computational learning theory and 5th European conference on computational learning theory. Springer, London, pp 416–426

Schwefel HP (1977) Numerische optimierung von computer-modellen mittel der evolutionsstrategie. Birkhuser, Basel

Silva C, Santos JS, Wanner EF, Carrano EG, Takahashi RHC (2009) Semi-supervised training of least squares support vector machine using a multiobjective evolutionary algorithm. In: Proceedings of the eleventh conference on congress on evolutionary computation, IEEE Press, Piscataway, NJ, USA, pp 2996–3002

Sindhwani V, Keerthi S, Chapelle O (2006) Deterministic annealing for semi-supervised kernel machines. In: Proceedings of the international conference on machine learning, pp 841–848

Steinwart I, Christmann A (2008) Support vector machines. Springer, New York

Suykens JAK, Vandewalle J (1999) Least squares support vector machine classifiers. Neural Process Lett 9(3):293–300

Valizadegan H, Jin R (2007) Generalized maximum margin clustering and unsupervised kernel learning. In: Advances in neural information processing systems, MIT Press, vol 19, pp 1417–1424

Vapnik V (1998) Statistical learning theory. Wiley, New York

Xu L, Schuurmans D (2005) Unsupervised and semi-supervised multi-class support vector machines. In: Proceedings of the national conference on artificial intelligence, pp 904–910

Xu L, Neufeld J, Larson B, Schuurmans D (2005) Maximum margin clustering. In: Advances in neural information processing systems vol 17, pp 1537–1544

Zhang K, Tsang IW, Kwok JT (2007) Maximum margin clustering made practical. In: Proceedings of the international conference on machine learning, pp 1119–1126

Zhao B, Wang F, Zhang C (2008a) Efficient maximum margin clustering via cutting plane algorithm. In: Proceedings of the SIAM international conference on data mining, pp 751–762

Zhao B, Wang F, Zhang C (2008b) Efficient multiclass maximum margin clustering. In: Proceedings of the international conference on machine learning, pp 1248–1255

Zhu X, Goldberg AB (2009) Introduction to semi-supervised learning. Morgan and Claypool, Seattle

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by funds of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Fabian Gieseke, grant KR 3695) and by the Academy of Finland (Tapio Pahikkala, grant 134020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Sparse approximation

We will now depict the approximation scheme for the kernel matrix K, which is based on the so-called Nyström approximation

see, e.g., [24]. Plugging in this approximation into (10), we get

as new objective value. The matrix \(\overline{{\bf K}} = {\bf D} \widetilde{{\bf K}} {\bf D}\) has (at most) r non-zero eigenvalues. To compute them efficiently, we make use of the following derivations: Let B B T be the Cholesky decomposition of the matrix (K R,R )−1 and \({\bf U} \varvec{\Upsigma} {\bf V}^{\rm T}\) be the thin singular value decomposition of B T K R D. The r nonzero eigenvalues of

can then be obtained from \({\varvec{\Upsigma}^2 \in {\mathbb R}^{r\times r}}\) and the matrix \({{\bf V} \in {\mathbb R}^{n \times r}}\) consists of the corresponding eigenvectors (we have U T U = I, see below). By assuming that these non-zero eigenvalues are the first r elements in the matrix \({\varvec{\Uplambda} \in {\mathbb R}^{n \times n}}\) of eigenvalues (of \(\widetilde{{\bf K}}\)), we have \([\varvec{\Uplambda} \tilde{\varvec{\Uplambda}}]_{i,i} = 0\) for \(i=r + 1,\ldots, n; \) hence, the remaining eigenvectors (with eigenvalue 0) do not have to be computed for the evaluation of (13). To sum up, y T D V can be updated in \(\mathcal{O}(r)\) time per single coordinate flip. Further, all preprocessing matrices can be obtained in \(\mathcal{O}(n r^2)\) runtime (in practice and up to machine precision) using \(\mathcal{O}(n r)\) space.

Appendix 2: Matrix calculus

For completeness, we summarize some basic definitions and theorems of the field of matrix calculus that may be helpful when reading the paper. The following definitions and facts are taken from [19] and [16].

Definition 1

(Positive (Semi-)Definite Matrices) A symmetric matrix \({{\bf M}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) is said to be positive definite if

and positive semidefinite if

We use the notations \({\bf M} \succ 0\) and \({\bf M} \succeq 0\) if M is positive definite or positive semidefinite, respectively. It is straightforward to derive that if \({{\bf M}_1,\ldots,{\bf M}_p\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) are positive definite matrices and \({\alpha_1, \ldots, \alpha_p \in {\mathbb R}}\) are positive coefficients, then

is positive definite as well, i.e., any positive linear combination of positive definite matrices is positive definite ([19], pp. 396–398). A lower triangular matrix is a matrix, where the entries above its diagonal are zero.

Fact 1

(Cholesky Decomposition) Any symmetric positive definite matrix \({{\bf M}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) can be factorized as

where \({{\bf N}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) is a lower triangular matrix whose diagonal entries are strictly positive. This factorization is known as the Cholesky decomposition.

The Cholesky decomposition for a m × m-matrix can be obtained in O(m 3) time (in practice and up to machine precision, see [16] pp. 141–145).

Definition 2

(Orthogonal Matrix) A matrix \({{\bf M}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) is called orthogonal if

i.e., if the inverse M −1 of a M equals its transpose M T.

Fact 2

(Singular Value Decomposition) A matrix \({{\bf M}\in{\mathbb R}^{m\times n}}\) can be written in the form

where \({{\bf U}\in{\mathbb R}^{m\times m}}\) and \({{\bf V}\in{\mathbb R}^{n\times n}}\) are orthogonal, and where \({\varvec{\Upsigma}\in{\mathbb R}^{m\times n}}\) is a diagonal matrix with non-negative entries. The decomposition is called the singular value decomposition (SVD) of M.

The values on the diagonal matrix are called the singular values of M; they are usually arranged in descending order, i.e., \({[\varvec{\Upsigma}]}_{1,1}\geq \ldots \geq{[\varvec{\Upsigma}]}_{p,p}\) with p = min(n, m).

Fact 3

(Thin Singular Value Decomposition) The thin or economy-size singular value decomposition of \({{\bf M}\in{\mathbb R}^{m\times n}}\) with m ≥ n is of the form

where \({{\bf U}\in{\mathbb R}^{m\times n}, \varvec{\Upsigma}\in{\mathbb R}^{n \times n}, }\) and \({{\bf V}\in{\mathbb R}^{n \times n}}\). Further, we have U T U = V T V = V V T = I (but not U U T = I).

Note that the thin singular value decomposition for a matrix \({{\bf M} \in{\mathbb R}^{n\times m}}\) can be computed in O(nm 2) time (in practice and up to machine precision, see [16] p. 239).

Fact 4

(Eigendecomposition) If \({{\bf M}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) is symmetric, then it can be factorized as

where \({{\bf V}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) is an orthogonal matrix containing the eigenvectors of M and \(\varvec{\Uplambda}\) is a diagonal matrix containing the corresponding eigenvalues ( [19], p. 107).

Note that if the nonzero eigenvalues are stored in the first r diagonal entries of \(\varvec{\Uplambda}, \) then (analogously to the economy-sized singular value decomposition) the matrix M can be written as in (27) but with \({{\bf V}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times r}}\) and \({\varvec{\Uplambda}\in\mathbb{R}^{r\times r}}\).

Fact 5

(SVD and Eigendecomposition) We have the following relationship between the SVD and the eigendecomposition. If (25) or (26) is the SVD of \({{\bf M}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\), then

is the eigendecomposition of M T M. Here, the eigenvalues of the matrix M T M are the squares of the singular values of M. Note that an analogous relationship also holds between the economy-sized decompositions.

Fact 6

(Further Matrix Properties) If \({{\bf M}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) is a (symmetric) positive definite matrix and \({\bf M}={\bf V}\varvec{\Uplambda}{\bf V}^{\rm T}\) is its eigendecomposition, then

that is, the eigenvalues of positive definite matrices are strictly positive real numbers ([19], p. 398). From this, it follows that all positive definite matrices are invertible and their inverse matrices are also positive definite. Moreover, we have

that is, all principal submatrices of M are positive definite ([19], p. 397). Further, if \({{\bf M}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times m}}\) is symmetric positive definite, then we have

This is a special case of the Observation 7.7.2 given by Horn and Johnson [19].

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gieseke, F., Kramer, O., Airola, A. et al. Efficient recurrent local search strategies for semi- and unsupervised regularized least-squares classification. Evol. Intel. 5, 189–205 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12065-012-0068-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12065-012-0068-5