Abstract

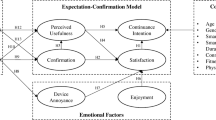

The initial healthy uptake of wearable devices is not necessarily accompanied by sustained or continued use. Accordingly, this study investigates the factors influencing the continuous use of wearable devices with a particular emphasis on design features. We complemented the expectation-confirmation model (ECM) theoretical foundation with various design features such as trust, readability, dialogue support, personalization, device battery, appeal, and social support. The study employs a simultaneous mixed method research design denoted as QUANT + qual. The quantitative analysis leverages partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using survey data collected from wearable device users. The qualitative analysis complements the quantitative focus of the research by providing insights into the results obtained from the quantitative analysis. We found that subjects tend to use wearables daily (60%) or several times a week (33%), and 91% plan to use them even more. Subjects indicated multiple usages for wearables. Most subjects were using wearables for healthcare and wellness (61%) or sports and fitness (54%) and had smartwatches wearable type (74%). The model explains 24.1% (p < 0.01) of the variance of continued intention to use. As a theoretical contribution, the findings support using the ECM as a theoretical foundation for explaining the continued use of wearables. Partial least squares (PLS) and qualitative data analysis highlight the relative importance that wearable users place on perceived usefulness. Most notable are tracking functions and design features such as device battery, integration with other apps/devices, dialogue support, and appeal.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wright R, Keith L (2014) Wearable technology: if the tech fits, wear it. J Electron Resour Med Libr 11:204–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2014.969051

MarketsandMarkets (2021) Global wearable technology market size, share trends analysis trends 2022-2026. https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/wearable-electronics-market-983.html. Accessed 12 Jan 2023

Precedence Research (2022) Wearable Technology market size, trends, growth, Report 2030. https://www.precedenceresearch.com/wearable-technology-market. Accessed 12 Jan 2023

Motti VG, Caine K (2015) Users’ privacy concerns about wearables. In: Brenner M, Christin N, Johnson B, Rohloff K (eds) Financial cryptography and data security. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 231–244

Mercer K, Li M, Giangregorio L, Burns C, Grindrod K (2016) Behavior change techniques present in wearable activity trackers: a critical analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 4:e40–e40. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.4461

Warraich MU (2016) Wellness routines with wearable activity trackers: a systematic review. In: Tenth Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems (MCIS), Paphos, Cyprus, p 14

Hendker A, Jetzke M, Eils E, Voelcker-Rehage C (2020) The implication of wearables and the factors affecting their usage among recreationally active people. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:8532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228532

Gribel L, Regier S, Stengel I (2016) Acceptance factors of wearable computing: an empirical investigation. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Network Conference (INC 2016). pp 62–72

El-Gayar O, Nasralah T, Elnoshokaty A (2019) Wearable devices for health and wellbeing: design insights from Twitter. In: 52nd Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences (HICSS-52’19). IEEE Computer Society, Maui, HI

Kalantari M (2017) Consumers’ adoption of wearable technologies: literature review, synthesis, and future research agenda. Int J Technol Mark 12:274. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTMKT.2017.089665

Ahmad A, Rasul T, Yousaf A, Zaman U (2020) Understanding factors influencing elderly diabetic patients’ continuance intention to use digital health wearables: extending the technology acceptance model (TAM). J Open Innov Technol Mark Complex 6:81. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6030081

Canhoto AI, Arp S (2017) Exploring the factors that support adoption and sustained use of health and fitness wearables. J Destin Mark Manag 33:32–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2016.1234505

Nascimento B, Oliveira T, Tam C (2018) Wearable technology: what explains continuance intention in smartwatches? J Retail Consum Serv 43:157–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.03.017

Shin G, Feng Y, Jarrahi MH, Gafinowitz N (2019) Beyond novelty effect: a mixed-methods exploration into the motivation for long-term activity tracker use. JAMIA Open 2:62–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooy048

Clawson J, Pater JA, Miller AD, Mynatt ED, Mamykina L (2015) No longer wearing: investigating the abandonment of personal health-tracking technologies on craigslist. In: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing - UbiComp ’15. ACM Press, Osaka, Japan, pp 647–658

Epstein DA, Caraway M, Johnston C, Ping A, Fogarty J, Munson SA (2016) Beyond abandonment to next steps: understanding and designing for life after personal informatics tool use. In: Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, San Jose California, USA, pp 1109–1113

Jeong H, Kim H, Kim R, Lee U, Jeong Y (2017) Smartwatch wearing behavior analysis: a longitudinal study. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol 1:1–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3131892

Lazar A, Koehler C, Tanenbaum J, Nguyen DH (2015) Why we use and abandon smart devices. In: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing - UbiComp ’15. ACM Press, Osaka, Japan, pp 635–646

Bhattacherjee A (2001) Understanding information systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q 25:351. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250921

Thong J, Hong S-J, Tam KY (2006) The effects of post-adoption beliefs on the expectation-confirmation model for information technology continuance. Int J Hum-Comput Stud 64:799–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.05.001

Lee AS (1999) Rigor and relevance in MIS research: beyond the approach of positivism alone. MIS Q 23:29–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/249407

Mingers J (2001) Combining IS research methods: towards a pluralist methodology. Inf Syst Res 12:240–259. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.12.3.240.9709

Niknejad N, Hussin ARC, Ghani I, Ganjouei FA (2020) A confirmatory factor analysis of the behavioral intention to use smart wellness wearables in Malaysia. Univers Access Inf Soc 19:633–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-019-00663-0

Rodríguez I, Cajamarca G, Herskovic V, Fuentes C, Campos M (2017) Helping elderly users report pain levels: a study of user experience with mobile and wearable interfaces. Mob Inf Syst 2017:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9302328

Chau KY, Lam MHS, Cheung ML, Tso EKH, Flint SW, Broom DR, Tse G, Lee KY (2019) Smart technology for healthcare: exploring the antecedents of adoption intention of healthcare wearable technology. Health Psychol Res 7. https://doi.org/10.4081/hpr.2019.8099

Cheung ML, Chau KY, Lam MHS, Tse G, Ho KY, Flint SW, Broom DR, Tso EKH, Lee KY (2019) Examining consumers’ adoption of wearable healthcare technology: the role of health attributes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph1613225

Dai B, Larnyo E, Tetteh EA, Aboagye AK (2020) Musah, A.-A.I.: Factors affecting caregivers’ acceptance of the use of wearable devices by patients with dementia: an extension of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. Am J Alzheimers Dis Dementias® 35:153331751988349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317519883493

Shih PC, Han K, Poole ES, Rosson MB, Carroll JM (2015) Use and adoption challenges of wearable activity trackers. iConference. University of California, Irvine, p 12

Adapa A, Nah FF-H, Hall RH, Siau K, Smith SN (2018) Factors influencing the adoption of smart wearable devices. Int J Human–Computer Interact 34:399–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2017.1357902

Epstein DA, Eslambolchilar P, Kay J, Meyer J, Munson SA (2021) Opportunities and challenges for long-term tracking. In: Karapanos E, Gerken J, Kjeldskov J, Skov MB (eds) Advances in Longitudinal HCI Research. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 177–206

Pal D, Funilkul S, Vanijja V (2020) The future of smartwatches: assessing the end-users’ continuous usage using an extended expectation-confirmation model. Univers Access Inf Soc 19:261–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-018-0639-z

Dehghani M (2018) Exploring the motivational factors on continuous usage intention of smartwatches among actual users. Behav Inf Technol 37:145–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1424246

Dehghani M, Kim KJ, Dangelico RM (2018) Will smartwatches last? Factors contributing to intention to keep using smart wearable technology. Telemat Inform 35:480–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.01.007

Anderson E, Sullivan M (1993) The antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction for firms. Mar Sci 12:125–143

Oliver R (1980) A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J Market Res 20:460–469

Oliver RL (1993) Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. J Consum Res 20:418–430. https://doi.org/10.1086/209358

Kim DJ, Ferrin DL, Rao HR (2009) Trust and satisfaction, two stepping stones for successful e-commerce Relationships: a longitudinal exploration. Inf Syst Res 20:237–257. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1080.0188

Chen L, Meservy T, Gillenson M (2012) Understanding information systems continuance for information-oriented mobile applications. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 30. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.03009

Hsu C-L, Lin JC-C (2015) What drives purchase intention for paid mobile apps? – An expectation confirmation model with perceived value. Electron Commer Res Appl 14:46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2014.11.003

Tam C, Santos D, Oliveira T (2020) Exploring the influential factors of continuance intention to use mobile apps: extending the expectation confirmation model. Inf Syst Front 22:243–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-018-9864-5

Oghuma AP, Libaque-Saenz CF, Wong SF, Chang Y (2016) An expectation-confirmation model of continuance intention to use mobile instant messaging. Telemat Inform 33:34–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.05.006

Susanto A, Chang Y, Ha Y (2016) Determinants of continuance intention to use the smartphone banking services: an extension to the expectation-confirmation model. Ind Manag Data Syst 116:508–525. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-05-2015-0195

Wairimu J, Sun J (2018) Is smartwatch really for me? An expectation-confirmation perspective. In: Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, p 10

Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 13:319. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Parthasarathy M, Bhattacherjee A (1998) Understanding post-adoption behavior in the context of online services. Inf Syst Res 9:362–379

Brown V (2005) Model of adoption of technology in households: a baseline model test and extension incorporating household life cycle. MIS Q 29:399. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148690

Hew J-J, Lee V-H, Ooi K-B, Wei J (2015) What catalyses mobile apps usage intention: an empirical analysis. Ind Manag Data Syst 115:1269–1291. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-01-2015-0028

Kim SC, Yoon D, Han EK (2016) Antecedents of mobile app usage among smartphone users. J Mark Commun 22:653–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2014.951065

Limayem H (2007) Cheung: How habit limits the predictive power of intention: the case of information systems continuance. MIS Q 31:705. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148817

Vodanovich S, Sundaram D, Myers M (2010) Research commentary—digital natives and ubiquitous information systems. Inf Syst Res 21:711–723. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1100.0324

Zhang P, Carey J, Te’eni, D., Tremaine, M. (2005) Integrating human-computer interaction development into the systems development life cycle: a methodology. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 15. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01529

Oinas-Kukkonen H, Harjumaa M (2009) Persuasive systems design: key issues, process model, and system features. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 24:485–500

Rahmati A, Qian A, Zhong L (2007) Understanding human-battery interaction on mobile phones. In: Proceedings of the 9th international conference on Human computer interaction with mobile devices and services - MobileHCI ’07. ACM Press, Singapore, pp 265–272

Chattaraman V, Rudd NA (2006) Preferences for aesthetic attributes in clothing as a function of body image, body cathexis and body size. Cloth Text Res J 24:44–61

Coorevits L, Coenen T (2016) The rise and fall of wearable fitness trackers. Acad Manag Proc 2016:17305. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2016.17305abstract

Jeong SC, Byun JS, Jeong YJ (2016) The effect of user experience and perceived similarity of smartphone on acceptance intention for smartwatch. ICIC Express Lett 10:8

Page T (2015) Barriers to the adoption of wearable technology. -Manag. J Inf Technol 4(1–13). https://doi.org/10.26634/jit.4.3.3485

Gan C, Li H (2018) Understanding the effects of gratifications on the continuance intention to use WeChat in China: a perspective on uses and gratifications. Comput Hum Behav 78:306–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.003

Liu N, Yu R (2017) Identifying design feature factors critical to acceptance and usage behavior of smartphones. Comput Hum Behav 70:131–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.073

Abdul-Rahman A, Hailes S (2000) Supporting trust in virtual communities. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE Comput. Soc, Maui, HI, USA, p 9. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2000.926814

Harrison McKnight D, Choudhury V, Kacmar C (2002) The impact of initial consumer trust on intentions to transact with a web site: a trust building model. J Strateg Inf Syst 11:297–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-8687(02)00020-3

Gefen K (2003) Straub: Trust and TAM in online shopping: an integrated model. MIS Q 27:51. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036519

Gu Z, Wei J, Xu F (2016) An empirical study on factors influencing consumers’ initial trust in wearable commerce. J Comput Inf Syst 56:79–85

Gottlieb BH, Bergen AE (2010) Social support concepts and measures. J Psychosom Res 69:511–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.001

Liu Y, Su X, Du X, Cui F, Liu Y, Su X, Du X, Cui F (2019) How social support motivates trust and purchase intentions in mobile social commerce. Rev Bras Gest Neg 21:839–860. https://doi.org/10.7819/rbgn.v21i5.4025

Al-Ramahi MA, Liu J, El-Gayar OF (2017) Discovering design principles for health behavioral change support systems. ACM Trans Manag Inf Syst 8:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1145/3055534

McCallum C, Rooksby J, Gray CM (2018) Evaluating the impact of physical activity apps and wearables: interdisciplinary review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 6:e58. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.9054

Bhattacherjee A, Barfar A (2011) Information technology continuance research: current state and future directions. Asia Pac J Inf Syst 21:1–18

Lee S, Kim D-Y (2018) The effect of hedonic and utilitarian values on satisfaction and loyalty of Airbnb users. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 30:1332–1351. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0504

Chen S, Chen H, Chen M (2009) Determinants of satisfaction and continuance intention towards self-service technologies. Ind Manag Data Syst 109:1248–1263. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570911002306

Kim KJ, Shin D-H (2015) An acceptance model for smart watches: implications for the adoption of future wearable technology. Internet Res 25:527–541. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-05-2014-0126

Sundar SS, Tamul DJ, Wu M (2014) Capturing “cool”: measures for assessing coolness of technological products. Int J Hum-Comput Stud 72:169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2013.09.008

Hwang C, Chung T-L (2016) Sanders, E.A.: Attitudes and purchase intentions for smart clothing: examining U.S. consumers’ functional, expressive, and aesthetic needs for solar-powered clothing. Cloth Text Res J 34:207–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X16646447

Cobos, L. (2017) Determinants of continuance intention and word of mouth for hotel branded mobile app users., https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5719

Venkatesh V, Davis FD (2000) A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Manag Sci 46:186–204. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926

Rustam V (2012) Design-type research in information systems: findings and practices. IGI Global, Ukraine

Shchiglik C, Barnes SJ (2004) Evaluating website quality in the airline industry. J Comput Inf Syst 44:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2004.11647578

Baleghi-Zadeh S, Ayub A, Mahmud R, Daud S (2017) The influence of system interactivity and technical support on learning management system utilization. Knowl Manag E-Learn Int J:50–68. https://doi.org/10.34105/j.kmel.2017.09.004

Creswell JW, Plano C, Hanson WE (2003) Advanced mixed methods research designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, Gutmann ML (eds) Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. SAGE Publications, Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA, US

Morse JM (1991) Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nurs Res 40:120–123

Götz O, Liehr-Gobbers K, Krafft M (2010) Evaluation of structural equation models using the partial least squares (PLS) approach. In: Esposito Vinzi V, Chin WW, Henseler J, Wang H (eds) Handbook of Partial Least Squares. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 691–711

Urbach N, Ahlemann F (2010) Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. J Inf Technol Theory Appl 11:36

Hair J, Hult T, Ringle C, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publications, Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA, US

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112:155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Gefen D, Straub D (2005) A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-GRAPH: tutorial and annotated example. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 16:91–109

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing 20:277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Market Res 18:39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA (2012) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Market Sci 40:414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

Chiu C-M, Hsu M-H, Sun S-Y, Lin T-C, Sun P-C (2005) Usability, quality, value and e-learning continuance decisions. Comput Educ 45:399–416

Grégoire Y, Fisher RJ (2006) The effects of relationship quality on customer retaliation. Mark Lett 17:31–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-006-3796-4

Charmaz K (2006) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, Thousand Oaks, CA, US

Strauss AL, Corbin JM (1998) Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, US

Karapanos E, Gouveia R, Hassenzahl M, Forlizzi J (2016) Wellbeing in the making: peoples’ experiences with wearable activity trackers. Psychol Well-Being 6:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13612-016-0042-6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Gayar, O., Elnoshokaty, A. Factors and Design Features Influencing the Continued Use of Wearable Devices. J Healthc Inform Res 7, 359–385 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-023-00135-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-023-00135-4