Abstract

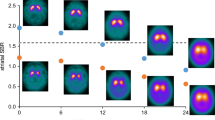

Neural networks are commonly used for the classification and segmentation of medical images. Interpretability of these models is still an area of active research. While progress has been made in visualizing areas on which convolutional neural networks (CNNs) focus most, the results are often only interpreted qualitatively. There exists a need to extend this interpretation methodology to make statistical inferences about how the network is classifying examples. The current study employs a multivariate statistical framework on activation maps from CNN classification of neuroimaging data to improve interpretability of the output. Ioflupane-123 SPECT scans from 600 participants in the Parkinson’s Progressive Markers Initiative database were classified into individuals with Parkinson’s disease and healthy controls using a 3D-adaptation of the ResNet-34 architecture. 3D-Grad-CAM was used to construct activation maps, giving the probability, at each voxel, that the network used that voxel for its final classification. These activation maps were then used in a multivariate modeling framework that corrects for multiple comparisons and spatial correlations. The multivariate model employed investigated differences in activation maps between PD and controls while controlling for age. Results showed expected regions of focus in the basal ganglia, but also showed significant differences along the nigrostriatal pathway, extending into the midbrain, an area not typically used for diagnosis. Numerous advantages stem from this framework, including greater network diagnostics, the ability to control for covariates that could be affecting network performance, and production of interpretable results that can be translated clinically to the bedside.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of Data and Material

All data used are publicly available on the PPMI database website after creation of an account (https://www.ppmi-info.org/access-data-specimens/download-data/).

Code Availability

All code used to perform analyses can be found on GitHub (https://github.com/willi3by/PPMI_Project).

References

Lundervold AS, Lundervold A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Arxiv. 2018;29(2):102–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zemedi.2018.11.002.

Samek W, Wiegand T, Müller KR. Explainable artificial intelligence: understanding, visualizing and interpreting deep learning models. 2017.

Buhrmester V, Münch D, Arens M. Analysis of explainers of black box deep neural networks for computer vision: a survey. 2019.

Anwar SM, Majid M, Qayyum A, Awais M, Alnowami M, Khan MK. Medical image analysis using convolutional neural networks: a review. J Med Syst. 2018;42(11):226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-018-1088-1.

He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. 2015.

Ebrahimi A, Luo S, Chiong R. Introducing transfer learning to 3D ResNet-18 for Alzheimer’s disease detection on MRI images. In: 2020 35th international conference on image and vision computing New Zealand (IVCNZ), 2020, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/IVCNZ51579.2020.9290616.

Cheng J, et al. ResGANet: residual group attention network for medical image classification and segmentation. Med Image Anal. 2022;76: 102313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2021.102313.

Lim B, Son S, Kim H, Nah S, Lee KM. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. 2017.

Yang C, Rangarajan A, Ranka S. Visual explanations from deep 3D convolutional neural networks for Alzheimer’s disease classification. 2018.

Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, Batra D. Grad-CAM: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. Arxiv. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-019-01228-7.

Mongan J, Moy L, Kahn CE. Checklist for artificial intelligence in medical imaging (CLAIM): a guide for authors and reviewers. Radiol Artif Intell. 2020;2(2): e200029. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.2020200029.

Marek K, et al. The Parkinson’s progression markers initiative (PPMI)—establishing a PD biomarker cohort. Ann Clin Transl Neur. 2018;5(12):1460–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.644.

Chang L-T. A method for attenuation correction in radionuclide computed tomography. IEEE T Nucl Sci. 1978;25(1):638–43. https://doi.org/10.1109/tns.1978.4329385.

Abadi M et al. TensorFlow: large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. 2016.

Chollet F, Keras. 2015. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/fchollet/keras.

Kingma DP, Ba J. Dam method for stochastic optimization. 2014.

Weng TW et al. Evaluating the robustness of neural networks: an extreme value theory approach. 2018.

Chen G, Adleman NE, Saad ZS, Leibenluft E, Cox RW. Applications of multivariate modeling to neuroimaging group analysis: A comprehensive alternative to univariate general linear model. Neuroimage. 2014;99:571–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.027.

Collier TJ, Kanaan NM, Kordower JH. Ageing as a primary risk factor for Parkinson’s disease: evidence from studies of non-human primates. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(6):359–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3039.

Ranganathan L, et al. Changing landscapes in the neuroimaging of dementia. Ann Indian Acad Neur. 2018;21(2):98. https://doi.org/10.4103/aian.aian_48_18.

Grahn JA, Parkinson JA, Owen AM. The role of the basal ganglia in learning and memory: neuropsychological studies. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199(1):53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.020.

Pianpanit T et al. Interpreting deep learning prediction of the Parkinson’s disease diagnosis from SPECT imaging. 2019.

Calle S, et al. Identification of patterns of abnormalities seen on DaTscanTM SPECT imaging in patients with non-Parkinson’s movement disorders. Rep Med Imaging. 2019;12:9–15. https://doi.org/10.2147/rmi.s201890.

Petersson KM, Nichols TE, Poline J-B, Holmes AP. Statistical limitations in functional neuroimaging. I. Non-inferential methods and statistical models. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 1999;354(1387):1239–60. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1999.0477.

Korchounov A, Meyer MF, Krasnianski M. Postsynaptic nigrostriatal dopamine receptors and their role in movement regulation. J Neural Transm. 2010;117(12):1359–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-010-0454-z.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conceptualization. BW performed the study design, formal analysis, data acquisition, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. VK assisted in data curation. DW assisted with the analysis. All authors reviewed, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethics Approval, Consent to Participate, Consent for Publication

All information on ethics approval, consent to participate, and consent for publication can be found in the PPMI documentation. Briefly, the PPMII study was performed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and Declaration of Helsinki guidelines, and was approved by the local ethics committee [9].

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williamson, B.J., Wang, D., Khandwala, V. et al. Improving Deep Neural Network Interpretation for Neuroimaging Using Multivariate Modeling. SN COMPUT. SCI. 3, 141 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01032-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01032-0