Abstract

Social aspects of software practitioners strongly influence software engineering outcomes. For instance, software companies seek to measure how factors like work engagement and job satisfaction impact employee productivity and software quality. Work engagement represents a positive, fulfilling, work-related mental state, while job satisfaction reflects how content professionals are with their roles. Our study aims to highlight the social aspects of software practitioners considering a large organization. We investigate the work engagement and job satisfaction of software practitioners working remotely at a large software organization in the public sector. We surveyed 891 software practitioners and analyzed their responses qualitatively and quantitatively. The survey participants indicated strong work engagement. They perceived their teams as effective, but there is room for improving social aspects, such as communication within the teams, promoting discussions about career development, and consistent feedback. Most professionals are satisfied with their teams, though a small minority expressed concerns that may influence their willingness to recommend their teams. Our findings provide relevant information about the engagement and satisfaction of employees within this particular type of organization and expand the knowledge base on the subject, supporting new research efforts in the area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To compete in the market, software companies face the challenge of enhancing quality while minimizing production costs. Achieving this goal involves addressing human factors like work engagement and job satisfaction [1]. Understanding human factors is essential for analyzing the judgments and decisions made by software practitioners. They significantly influence individual and team performance, productivity, and software quality [2, 3].

Work engagement reflects a positive dispositional state of mind, of pleasure and connection with the work activities, characterized by vigor, dedication, and concentration [4]. It relates to high levels of energy and devotion at work (vigor), importance and relevance (dedication), and mental resilience and concentration, along with a sense of significance, inspiration, pride, challenge, and concentration [5].

Job satisfaction refers to how content professionals are with their work, team, tools, or culture [6]. Satisfaction is one of the most valued dimensions of productivity in software development [6]. Researchers and companies recognize the relationship between productivity and job satisfaction [3].

Software companies are researching to understand how these factors affect software practitioners and gain insights into improving their performance. For example, researchers at Google discovered that the most effective teams excelled not because of who was on them but because of how well they collaborated [7]. They also emphasized that successful managers promote employee engagement and job satisfaction [8, 9]. Microsoft researchers developed a theory on software developer job satisfaction and perceived productivity, identifying work environment factors that influence both [3]. Software communities like Stack OverflowFootnote 1 are investigating what drives better performance and higher productivity and how to improve the developer experience. Its last survey reports that only one in five professional developers are satisfied with their current job [10]. Additionally, empirical studies highlight various factors affecting software engineers’ productivity, motivation, and satisfaction [11, 12]. These findings suggest that organizations can influence productivity by improving practitioners’ work experience, incorporating suitable practices to mediate relevant factors in their context [13].

Measuring practitioners’ work engagement and job satisfaction is essential in this context. Several soft and technical factors may impact work engagement and job satisfaction [3, 14]. Soft factors are related to human aspects. For instance, communication, team cohesion, autonomy, feedback, clear goals, and work complexity are examples of soft factors, while hardware and software tools are examples of technical factors.

Software companies must assess how these factors affect their work environment [12]. Moreover, the accelerating adoption of remote work has not so much increased the challenges of managing virtual teams but rather exposed the underlying gaps in management and leadership, reinforcing the need to examine what impacts them [15].

Investigating these constructs in practice is essential, as well as continuously building empirical knowledge about human aspects in software engineering under specific contexts such as team organization, process models, and organization characteristics.

Our study investigates the work engagement and job satisfaction of software practitioners working in a remote environment at Serpro,Footnote 2 the largest state-owned information technology company in Latin America. To this end, we surveyed 891 software practitioners and analyzed their responses qualitatively and quantitatively. We conducted this study in two phases. In the first, we surveyed a department of architects and process analysts, receiving 148 answers from its employees, and presented the results in Cerqueira et al. [16]. Based on this preliminary work, we surveyed other departments, receiving 743 answers from its employees who work as requirement engineers and software developers. The second study expands the preliminary work, presenting results based on a broader survey using the same instrument, but involving a more significant and diverse number of participants. It enables a more in-depth analysis of the factors that affect the engagement and satisfaction of the company’s professionals.

Therefore, this paper synthesizes the results from surveying 891 software practitioners regarding work engagement and job satisfaction. Practitioners can use our results to foster workplace improvement and software development teams’ satisfaction. Researchers can use our results to provide a grounded view of these human aspects in a software company, guiding new research efforts aligned with the demands and current context experienced by practitioners. The results contribute to building knowledge on the topic by considering a specific context: large governmental organization and remote work.

The paper is structured as follows. In the following section, we present related work on the influence of work engagement and job satisfaction in software engineering activities. Section Methodology presents the survey design, Section Results presents the results, and Section Discussion presents the discussions. Section Threats to Validity discusses the threats to the study’s validity and the strategies to mitigate them. Section Concluding Remarks concludes the paper with our final considerations and future perspectives.Footnote 3

Related Work

Software practitioners’ behaviors and emotional states can significantly influence their performance in work activities [17]. A developer’s productivity is strongly linked to their job satisfaction [3]. Software professionals faced challenges to their well-being, satisfaction, and productivity when they switched their working habits to a working-from-home (WFH) setting during the COVID-19 pandemic [18,19,20]. Engagement and job satisfaction are strongly related to the subjective practitioners’ perceptions and may vary according to different contexts, professionals, work environments, and organizations. Thus, measuring those aspects is one of the ways to assess the impacts of these changes in the work environment among a company’s professionals. This section presents studies investigating software practitioners’ work engagement and job satisfaction.

Wagner and Ruhe [14] conducted a systematic review of productivity factors in software development. They presented a list of technical and soft factors that influence productivity. Soft factors are aspects of human characteristics, such as management, feedback, communication, and appreciation for work. In contrast, technical factors relate to systems and process engineering, such as programming languages, tools, hardware, and processes [12, 14].

In alignment with the factors distilled by Wagner and Ruhe [14], Storey et al. [3] performed a study to understand and measure productivity and job satisfaction. The authors investigated the most significant soft-technical factors and challenges Microsoft developers face. As a result, they compiled a categorized list of soft and technical factors that can affect job satisfaction and productivity. Our work uses the categorization by Wagner and Ruhe [14] and Storey et al.[3].

In another related work, França et al. [11] conducted multiple case studies in four software organizations to present a theory of software engineers’ motivation and job satisfaction. According to the authors, these aspects have been objects of study in many different fields for a long time, but there is still little concern with the proper use of theories applied to software engineering [11].

Johnson et al. [21] presented a study to understand which factors related to the physical work environment affect the satisfaction and perceived productivity of software engineers who work in company offices. The authors found that the most critical factors were working privately without interruption and team and leaders’ communication. Different from Johnson et al. [21], our work also focuses on remote work environments.

Bezerra et al. [22] surveyed 58 software teams and examined how human and organizational factors influenced productivity in remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their key findings include: 82.70% are satisfied with the communication at work from home, 59.7% had an improvement in productivity in WFH, and 75% are confident with their productivity.

Marinho et al. [23] surveyed 102 software developers at a technology center to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their happiness. The study highlighted how the pandemic’s uncertainties, fears of infection, grief over lost loved ones, and reduced social interactions negatively affected developers’ well-being and work performance.

Following, Tokdemir [24] investigated software professionals’ mental well-being and work engagement, focusing on their relationships with job strain and resource factors during the forced home-based work setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study, conducted via an online survey in Turkey, included 321 software professionals. Results indicated that sleep quality, exercise, decision latitude, work-life balance, and job strain were key predictors of mental well-being. Similarly, sleep quality, decision latitude, and job strain influence work engagement. The study suggested monitoring and improving these factors during crises can significantly benefit software practitioners’ mental health and work engagement.

Silveira Neto et al. [19] explored the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on software projects and professionals. Using ten metrics, they analyzed 100 Java-based GitHub projects and surveyed 279 software developers to understand the pandemic’s effects on daily activities and well-being. They identified 12 key productivity, code quality, and well-being observations. The findings revealed that the impact of COVID-19 on productivity is not binary but exists along a spectrum.

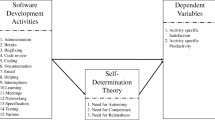

Russo et al. [20] surveyed 192 software engineers to assess how specific activities impacted their satisfaction and productivity during enforced remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study found that activity-specific factors, like autonomy during coding, significantly predicted satisfaction and productivity, while broader factors, like general resilience and work-life balance, had less impact.

Engagement and job satisfaction are based on the subjective practitioners’ perceptions and may vary according to different contexts, professionals, work environments, and organizations. Although there are studies on the satisfaction and engagement of software professionals, this specific context is still not widely studied, and cultural differences can impact the results [11]. We started understanding specific contexts in our preliminary study [16]. We surveyed 148 employees from Serpro and performed a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the responses [16]. We verified a good level of engagement and job satisfaction among the respondents, 63% of them would recommend their team to a friend. Furthermore, we identified 28 soft factors and two technical factors, which, according to the participants’ perception, can help the company improve satisfaction in the workplace. We identified that career development, psychological safety, team, management and rewards, benefits, meeting planning, and social interactions are the factors that most affect their satisfaction. The factors meeting planning and social interactions were not mentioned in previous work [3, 14]. Lastly, we provided a cheat sheet frame for work improvement based on the factors identified in the survey.

In the extension of our work, we surveyed 743 employees working in the same company. This extension complements the first investigation, presenting results based on a broader survey using the same instrument but involving a more significant number of participants. Table 1 compares our study to related work that addresses the impact of remote work during the pandemic on software developers’ factors, such as work engagement, job satisfaction, and productivity.

In total, this paper analyzes a dataset based on answers from 891 software practitioners, which improves on prior work, including:

-

A detailed analysis of the practitioners’ work engagement, psychological safety, team effectiveness, performance, allocation, and career development.

-

An assessment of the team members’ satisfaction with their teams.

-

A qualitative analysis of the factors affecting the work environment.

-

A comparative analysis of the results of our first investigation [16].

-

A set of additional factors that can affect practitioners’ satisfaction (compared to the literature and our previous work).

-

A comparative analysis of the factors affecting practitioners’ job satisfaction with different roles.

-

An extension of the cheat sheet frame for practitioners to support work improvement based on the factors identified in our survey.

This extended analysis will help drive new research efforts by further understanding factors affecting work engagement and job satisfaction of practitioners working remotely. It also can help practitioners use the body of knowledge to improve their working conditions. The following section discusses our research questions, data collection, and analysis procedures.

Methodology

This section presents the planning of the study, considering its context, the research questions, and data collection and analysis procedures.

Context

We performed the study at Latin America’s largest state-owned IT technology company. The company has around 7700 employees and is spread over several states of Brazil.Footnote 4 The study was conducted in the context of a project named Sinergia, which is being carried out in the company’s software development office, aiming to improve employees’ soft skills. Such skills consist of the capacity development for knowledge mobilization, practices, and attitudes that contribute to increasing the effectiveness of their results. Within the scope of Sinergia, the company aims to identify opportunities for improvement, track the evolution of implemented actions, and evaluate their return. The initiative is also expected to positively impact teams by clearly understanding their current competencies, establishing a baseline for growth, and enabling them to plan targeted improvement actions at both personal (for managers) and team levels.

We conducted the study in two phases. In the first one, we invited 225 employees and received answers from 148 (a 65% success rate). They were software architects, designers, and process analysts from a department responsible for defining architectural patterns and processes and supporting development teams. Last, we invited 905 employees and received 743 answers (an 82% success rate). At this time, they were managers, support, requirements engineers, and software developers from departments responsible for software development and digital solutions. We reported the results from the first phase in [16]. This current paper presents a complete data analysis by aggregating data from the first phase with those collected in the last one. The main difference between the two phases is related to the number of participants and the participant’s role in the organization.

Research Questions

Our study focuses on understanding factors that affect work engagement and job satisfaction [3, 14]. Thus, our questionnaire addresses multiple questions related to these factors, such as psychological safety, team effectiveness, performance, allocation, and career development, based on the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) [4] and the technical reports of Google projects [7, 9]. We defined the research questions based on the interest in independently organizing and understanding these factors. This way, we seek to capture how each factor relates to the organization’s central interests for improvements. Hence, our work has the following research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1: How is the work engagement in the teams? This question aims to assess employee engagement at work. It is motivated by engagement being related to other key job factors at the organizational level. For instance, there is a positive correlation between engagement and commitment to the job and a negative correlation between engagement and the intention to leave an organization [4]. There are also possible correlations between engagement and absenteeism, satisfaction, and job performance [26]. We adapted the UWES to measure work engagement [4].

-

RQ2: How do the teams assess the dimensions of psychological safety, team effectiveness, performance, allocation, and career development? Psychological safety is related to personal perceptions about the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in a context such as a workplace [27]. Team effectiveness encompasses factors such as cohesion and collaboration, as well as proactive communication, clear goals, autonomy, and work impact [3, 14, 28, 29]. The performance dimension intends to evaluate the team’s perceived productivity. The allocation dimension intends to identify situations of overload or idleness within the team and plays a critical role in the success of projects in software engineering [30]. The career development dimension intends to assess the perception of factors such as feedback, career development, and recognition for work [28, 29]. Examining these dimensions, this question investigates how people work together within their teams and the organization.

-

RQ3: How satisfied are the team members with their teams? This question aims to assess the satisfaction of the employees. Satisfaction refers to pleasurable emotions in reaction to work and influences attitudes towards the organization, such as intention to stay and job attendance [11]. One of the possible ways to measure satisfaction is to ask employees how much they would recommend their team to others [6].

-

RQ4: What factors can be improved in the work environment? This question aims to identify points that can improve the work environment, productivity, satisfaction, and well-being of team members. It works as a proxy to identify critical points of attention in the work environment.

Survey Instrument

Our study adopts a survey as a methodological instrument because productivity dimensions such as employee satisfaction and well-being are generally better evaluated with this research strategy [6]. The survey encompasses 20 questions. It starts with 18 questions in which the respondent evaluates the level of agreement with a given sentence on a 7-point scale (0—Never, 1—Almost never, 2—Occasionally, 3—Regularly, 4—Frequently, 5—Almost always, 6—Always.) Next, it has a question based on the Net Promoter Score (NPS) [31]. In our survey, NPS helps measure employees’ satisfaction with their team. Finally, the survey ends with an open-ended question asking what the respondents would change in their work environment. Table 2 presents the survey questions.

Questions 1–6 approach the employee satisfaction dimension. This set of questions is related to RQ1. They aim to assess the level of work engagement, considering that there is a relationship between work engagement and professional performance. The questions are based on the “Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES)” [4]. Questions 7–18 focus on psychological safety, performance effectiveness, allocation, and career development. The questions aim to assess the relationship among employees within the working team. This set of questions is related to RQ2. They are based on the technical reports of the Aristotle and Oxygen projects [7, 9]. Aristotle [7] is a Google Project that investigates hundreds of Google’s teams, focusing on understanding “why some stumbled while others soared.” Oxygen [9] is a Google Project focused on investigating “what makes a manager great at Google.” Question 19 aims to answer RQ3 and defines a team recommendation assessment to measure employee satisfaction within the team. It uses an NPS scale ranging from 0 to 10. Although NPS can be used to evaluate a company, product, or service, in our study, we asked employees how much they would recommend their team to a colleague to work with. This adaptation is often associated with the term e-NPS [31]. Lastly, for answering RQ4, question 20 asks the participant what he(she) would do if he(she) had a magic wand to improve his(her) work environment. It aims to identify critical points of improvement in the work environment.

Before applying the survey at large, we piloted it in an organizational unit of 79 people. We aimed to test the survey instrument with members of the study’s target population. We received 65 answers and got feedback about how long it took to complete the task (the mean time was about 12 min), impressions about questions (e.g., clarity, ease of understanding, size), and improvement points. We did not include these responses in the final survey results. We used this information only to refine the questionnaire by (i) improving the survey questions for clarity and completeness, i.e., internal and construct validity, and (ii) reducing the effort required to answer it.

Data Collection and Population

We conducted the first-phase survey between October 25th and November 08th, 2021, and the second one between February 14 and 23, 2022, with employees who worked remotely to develop software solutions. As previously highlighted, 148 respondents for the first-phase survey were software engineers, acting in the level of software architecture, design, processes, and supporting activities of the development teams. For the second-phase survey, the 743 respondents were developers involved in requirement analyses and programming. It is essential to highlight that the period of the survey application was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, the company has adopted work remotely. The respondents were from different geographical regions of the country and had worked between 10 and 30 years in this organization. They work as managers, architects, designers, support, requirements engineers, and developers in software development at Serpro.

The survey application was done synchronously in virtual meetings. In those meetings, we explained the purpose of the questionnaire and invited the attending employees to participate. The participation was voluntary, and those who decided to participate in the survey would be given 20 min to answer the questionnaire.

To ensure anonymity throughout the study, we refer to survey participants by a study ID number, namely \(P_1, P_2,... P_n\).

Data Analysis Procedures

The survey instrument is composed of a mix of closed and open-ended questions. Thus, we need to rely on various procedures for data analysis. To analyze the answers to closed questions (Q1–Q19), we relied on descriptive statistics to better understand the data. We used the mode and median for the central tendency of the ordinal and interval data. We calculated the distribution of participants choosing each option for the nominal data.

For the open-ended question (Q20), we applied qualitative data analysis techniques [32]. We coded responses to Q20 based on the list of technical and soft factors and their categories, as proposed by Wagner and Ruhe [14] and Storey et al. [3]. For instance, communication, collaboration, camaraderie, and team cohesion are soft factors in the team category, while hardware and tools are examples of technical factors in the processes and systems category.

Figure 1 shows examples of two answers coded as communication and feedback factors in the team and management categories, respectively. For instance, we coded the participant \(P_{56}\)’s response “I would improve communication. It is tough to get through to the team; they are always busy”Footnote 5 as communication in the Team category. In another example, we coded \(P_9\)’s answer “Get more feedback from my leaders” as Feedback in the Management category.

We coded responses to Q20 based on the list of categories and technical and soft factors proposed by Wagner and Ruhe [14] and Storey et al. [3] (see Section Related Work). However, the initial list of codes eventually evolved. During the coding process, we noticed that some answers did not fit any of the factors mentioned by those authors. Thus, we annotated these answers (as no category) and later grouped and categorized them by creating new factors. For instance, some practitioners mentioned the need to plan the meetings appropriately. Therefore, we annotated answers such as \(P_{720}\)’s “I would improve meeting times and address more people-related issues.” as the factor meeting planning. In this process, five new factors emerged: meeting planning, social interactions, allocation, remote working, and empathy, as explained later in the paper.

We performed the coding process in two stages. In the first, two researchers independently coded the answers from the first-phase survey. They collaboratively reviewed their classifications and reached a consensus on categorizing the responses. In the second stage, we divided the answers collected from the second-phase survey among three annotators (the two researchers and one practitioner from the company, who participated in the Sinergia project’s design). All three annotators independently coded the answers. Afterward, they conducted a consensus meeting to resolve the divergences.

In both stages of the coding process, to ensure accuracy and alignment with the organization’s context, their employees participated in discussions about the results.

Results

We present the results of the study in the following subsections.Footnote 6

RQ1—How is the Work Engagement in the Teams?

Figure 2 presents the results including all answers collected for the 18 closed questions of the survey. Q1–Q6 indicate how participants of the survey feel at work. We discuss them next.

Taking a look at Q1–Q6, we can notice a high level of work engagement among software practitioners. Regarding Q1, Q2, and Q3, we can see that most respondents considered themselves full of energy, enthusiastic about their work, and felt like going to work. A significant majority report positive feelings about their work, with most respondents frequently or almost always experiencing energy (75%), enthusiasm (72%), and pride (82%) in their work. This points to a deep connection with the work activity, characterized by vigor, dedication, and concentration, and therefore, less probability of absences and employee turnover [4]. Concerning questions Q4, Q5, and Q6, most participants considered themselves proud and involved in their work, and also that “time flies” when they were working. A considerable portion also feels motivated to go to work (73%) and becomes deeply immersed in their tasks, with 87% often or always feeling immersed and 82% finding that “time flies” while working. This denotes a sense of significance, inspiration, and pride in relation to their job [4]. Lastly, none of the participants answered Never for question 5, and only 1% for questions 1–4 and 6. Therefore, results indicate that the participants considered themselves engaged in their jobs.

RQ2—How do the Teams Assess the Dimensions of Psychological Safety, Team Effectiveness, Performance, Allocation, and Career Development?

Psychological safety, team effectiveness, performance, allocation, and career development are related to job satisfaction [3]. The results for these dimensions are shown in Q7 to Q18 of Fig. 2.

The answers to Q7 are related to psychological safety within software teams. The survey results indicate a generally positive sense of psychological safety within software teams, with 74% of respondents always, almost always, or frequently feeling they can fail or speak out without inhibition or pressure. However, a portion, 16%, still only occasionally or rarely feels this way. The data suggests that while most team members feel secure in expressing themselves and taking risks, there is room for improvement in fostering an environment where everyone consistently feels safe to speak up or fail without fear of negative consequences. Psychological safety is a significant factor for a team’s success, and establishing psychologically safe environments is essential to the organization [7]. It also can affect performance and job satisfaction [33].

Concerning team effectiveness (Q8–Q13) and performance (Q14), we can see a similar assessment by the majority of participants. The survey results suggest that software practitioners generally perceive their teams as effective. Regarding Q8–Q10, a large majority of respondents agree that team members follow through on their commitments (76%), communicate proactively (71%), and have a clear understanding of the team’s goals (64%). Autonomy within projects (Q11) is also positively viewed, with 61% of respondents feeling they have a reasonable degree of autonomy. Additionally, for Q12 and Q13, a significant portion feels that work is well-matched to their skills and interests (73%), and they see their work as contributing to a greater purpose (67%).

The answers to Q14 indicate a high level of satisfaction with team performance among software practitioners. A significant majority, 68% of respondents, express that they are frequently or almost always satisfied with their team’s performance, while only a tiny percentage, 7%, report low satisfaction.

The survey results reveal mixed perceptions among software practitioners regarding the balance of task allocation within their teams. While 46% of respondents frequently or almost always observe a balanced distribution of activities, with minimal overload or idleness, a significant portion, 34%, only occasionally or rarely notices such balance. This suggests that while some teams manage workload distribution effectively, others may struggle with ensuring that tasks are evenly allocated, potentially leading to instances of both overwork and idleness among team members. As software team building is an important project management activity, the right team size is critical to avoid allocation overhead issues [30]. Moreover, many software companies were unprepared for the sudden shift to remote work, leading to challenges in managing employee workloads effectively, which likely added extra pressure on software practitioners [19].

Regarding the career development dimension (Q16–Q18), the survey results indicate varied experiences among software practitioners. While 60% of respondents report receiving significant feedback from their leaders and teammates, a notable 27% feel they receive feedback only occasionally or rarely. Conversations about career development with managers are less common, with just 28% frequently engaging in such discussions, while 47% do so infrequently. On a positive note, a majority, 59%, feel appreciated by their managers for their work, though 19% rarely or never experience this recognition. Previous studies have pointed to the importance of the manager showing appreciation and giving good feedback about the work, as well as to the need for good communication within the team [3, 7, 14, 28].

RQ3—How Satisfied are the Team Members with Their Teams?

Figure 3 shows the participants’ evaluation for Q19 (How highly would you recommend your team (your division) to a friend to work in it?). The results indicate that 53% of software practitioners would recommend their team to a friend, reflecting a positive level of job satisfaction. Additionally, 33% provided neutral responses, indicating they may not have strong feelings either way. Meanwhile, 15% were less likely to recommend their team, suggesting there could be concerns about their local work environment. While the overall sentiment remains favorable, with the majority expressing satisfaction, the less favorable responses indicate that some practitioners may encounter challenges or uncertainties that could influence their readiness to fully endorse their team to others. The answers to the open question, discussed in the following section, can be a starting point for understanding the perception of the teams among the practitioners surveyed.

RQ4—What Factors can be Improved in the Work Environment?

Of the participants involved in the study’s first phase, 81 out of 148 provided feedback on their work environment, resulting in 103 coded responses covering 28 soft and two technical factors. Considering the study’s second phase, 568 participants offered feedback, yielding 683 responses. These responses generated 629 codes that we categorized into 55 soft factors and 54 codes categorized into three technical factors. A significant number of respondents in both studies expressed satisfaction with their work environment, with 43 explicitly stating no desire for change. For instance, \(P_{853}\) answered:

“The work environment in our team is exceptional and very good to work in.” [P853]

The combined results from both studies indicate a stronger emphasis on soft factors, with a total of 732 codes categorized into soft factors compared to 58 codes categorized into technical factors, reflecting the participants’ primary concerns and areas for potential improvement in their work environment.

Soft Factors

These are factors related to human aspects. Table 4 shows the coded categories and soft factors for the participants. The respondents showed more concern for factors within the Team, Management, Rewards, Benefits, and Career categories. Following that, we discuss the findings regarding each category and its factors. The value in parentheses is relative to the frequency of each category and coded factor.

Team. Responses in this category are linked to team improvements. It had the highest number of mentions, with practitioners emphasizing the need for better Communication (49) and increased Collaboration (36) within teams. Social interactions (28) and Skilled co-workers (21) were also highly valued. Factors like Team cohesion (14), Psychological safety (16), and Support for innovation (13) were noted as important. Practitioners also mentioned the importance of Camaraderie (9), a strong Team culture (7), and Empathy (6) within their teams. A smaller number highlighted the importance of Team identity (5).

Communication refers to the degree and efficiency with which information flows in the team [6, 14]. Respondents suggested improvements, including broader adoption of non-violent communication to improve the interactions between team members. For instance, practitioner \(P_{572}\) noted:

“I would improve aspects of nonviolent communication.” [P572]

Practitioners also mentioned the need for more empathy (6). Empathy is an interpersonal skill that can improve collaboration, communication, and relations between team members [34]. For instance, \(P_{366}\) mentioned:

“Improve employee empathy, enabling a more realistic and fair view of colleagues and encouraging support when necessary.” [P366]

The organization must intensify the adoption of good practices to maintain a communication flow between team members as this factor can be correlated to a project’s success and positively impact productivity [14]. Ensuring access to tools, infrastructure, and organizational resources, besides keeping communication channels open, sharing essential work information, and a space for informal talks are fundamental communication strategies for companies [21, 35, 36].

The social interactions factor concerns events, social connections and interactions between team members [36]. For instance, \(P_{342}\) reported:

“I would hold relaxed meetings with members once a month to chat about personal lives, experiences, and amenities to increase team integration.” [P342]

Participants also mentioned the psychological safety (16) factor, which we questioned in Q7 (see Fig. 2), in which some respondents (approximately 16%) think that never, almost never, or occasionally team members feel they can fail or speak out without feeling inhibited or pressured.

Management. In this category, factors refer to the team manager roles. Software practitioners identified several factors as areas for improvement. The most frequently mentioned was the role of the Manager (40), followed by the need for better Feedback (26) and Autonomy (24) in their roles. Other significant factors included the importance of Meeting planning (23), having Well-defined goals (20), and maintaining Clear priorities (13). Additionally, some practitioners expressed a desire for more Appreciation shown for work (13).

Managers are essential for making clear decisions and facilitating collaboration between teams, being decisive for the performance and efficiency of employees [9]. They must understand needs and be able to provide feedback to benefit their engineers [3].

As for the meeting planning factor, responses mentioned problems in the proper planning of meetings. This factor had not been previously listed as an important factor for practitioners by Storey et al. [3] and Wagner and Ruhe [14]. However, our survey participants mentioned the need for better planning and organization of meetings to use their time better. Too many meetings or poorly conducted meetings can become a waste of time and a challenge for developer productivity [28, 35].

Feedback relates to giving information about performance effectiveness. Software engineers suffer from a low level of feedback, while direct and immediate evaluation contributes to understanding work results and building a self-perception of their actual performance [11, 28]. This aligns with the answers to question Q16, in which 27% indicated they receive feedback only occasionally or rarely (see Fig. 2). For example, \(P_{25}\) reported that he(she) wanted to “Get more feedback from my leaders.”

Rewards, benefits, and career. In this category, Promotions (39) were the most mentioned factor, indicating a strong desire for career advancement. For instance, \(P_{426}\) responded:

“I would improve the way employees are valued and promoted based on merit.” [P426]

Practitioners also emphasized the need for more Lateral move opportunities (21), better Benefits (17), and Salary (17). Job security (7) was also a concern for some practitioners.

This shows that some participants also want more equity in distributing promotions and salary progression. Managers can propose alternative incentive strategies to address these challenges, such as useful knowledge as a reward [11]. Besides, they want more opportunities to change projects or teams. Improving these factors can contribute significantly to a positive work environment and help retain talent by meeting both professional and personal needs.

Project. In the Project category, practitioners expressed a desire to improve several key factors to enhance their job satisfaction. Team size (43) is the factor that stands out, emphasizing the importance of having an appropriate number of team members to handle the project’s demands effectively. For instance, \(P_{509}\) cited:

“I would increase the number of team members” [P509]

Practitioners also noted concerns about the Schedule (13), highlighting the need for realistic timelines to reduce stress and improve productivity. In addition, Allocation (9) refers to the efficient distribution of resources and tasks. Requirements stability (2) was mentioned by a small number of respondents. It focuses on having clear and consistent project requirements to avoid confusion and rework.

Working environment. In this category, remote working (11) was a notable factor, indicating a growing preference among practitioners for flexible work arrangements. For instance, practitioner \(P_{203}\) stated:

“I would make remote work permanent as there was a clear increase in the quality and volume of deliveries.” [P203]

One important aspect to consider, though, is how to promote and keep Proximity to the team (16). As practitioner \(P_{727}\) expressed a desire for hybrid work, highlighting the importance of face-to-face contact with colleagues:

“I would leave the option of hybrid work so that employees could have face-to-face contact with other team members.” [P727]

Other factors included Physical working environment (9), Telecommunication facilities (4) essential for seamless communication, the need for Private working space (3), and e-factor (7) that likely reflects the significance of reducing interruptions in the work environment.

[21] noticed that for some software engineers, team proximity is significant, as perceived productivity and satisfaction can increase when the people they work with are nearby. Due to the collaborative nature of software development, the ability to informally sense if someone is available to initiate a discussion can facilitate many tasks [21].

E-factor is related to work interruptions. Software engineers may feel less satisfied or less productive with their work depending on how many interruptions and context changes they face [14]. Interruptions can occur in shared physical work environments (colleagues talking, telephone, office noise) as well as in remote work (family, children, pets, ambient noise) and can delay the work progress [21, 28]. Working in privacy without interruption is a major factor in satisfaction with the work environment [21]. Therefore, some software engineers prefer to work in private spaces [3]. However, the ability to communicate and work collaboratively is also valued. Hence, managers and leaders must balance the need for individual privacy with the need for team communication.

Work type/impact. The complexity and nature of work were important to practitioners, with Work complexity (19) being the most frequently mentioned factor in this category. Some feel their Skills are well used (7), while others mention jobs requiring a lot of skill (2). The ability to Complete tasks (4) and the Time it takes to learn the job (4) were also noted as areas for improvement. As some practitioners mentioned, the Type of work (6) factor highlights a desire for roles aligning with their competencies and interests and engaging in meaningful projects. This can provide a sense of accomplishment and expertise, as P219 mentioned:

“I would choose to work in something more enjoyable than my current activities.” [P219]

Some job complexity factors can affect job performance and well-being, as it can increase satisfaction by challenging software engineers [3]. However, the company must balance the complexity and the time available to complete the tasks.

Work life/work experience. In terms of work-life balance, respondents mentioned three key factors for improving their satisfaction at work: Stress, Work-life balance, and Time to complete tasks. Stress (15) points to the pressure and demands of the job, an opportunity of better stress management and support, as P780 mentions:

“[I would] make our work less stressful.” [P780]

Work-life balance (10) emphasizes the need for a healthy equilibrium between professional responsibilities and personal life, which is crucial for overall well-being. Moreover, they mentioned time to complete tasks (13), underscoring the importance of realistic deadlines and efficient time management.

Training. Training was another area where practitioners sought improvement, mostly mentioning Training for engineering technologies (23). Training for soft skills (13) and learning skills useful for the future (4) were also necessary.

Although the survey focused on developing soft skills, practitioners highlighted the need for additional training in engineering technologies (23) to stay current with the latest tools and methodologies.

They also emphasized the importance of training in soft skills (13) to enhance communication, teamwork, and leadership abilities, which are essential for comprehensive professional development. For instance, \(P_{660}\) stated the need for more training to improve empathy between team members:

“I would train some people with social-emotional skills, as some people lack empathy for the work of others.” [P660]

It is critical that software engineers broaden their skills, specialize in the domain of tools and technologies, and also widen their soft skills [3].

Individual skills and experiences. In this category, practitioners mentioned the importance of Happiness (12) in their roles, along with aspects of Personality (4), which encompasses conflicts between different temperaments in the team.

The combination of different temperaments and personalities can affect the performance and satisfaction of team members, which is important for the good co-existence, communication, collaboration, and psychological safety of the team [14].

Happiness is essential for well-being and productivity while acknowledging and supporting individual personality traits can enhance team dynamics and personal fulfillment [37]. \(P_{645}\), for example, cited:

“I would make everyone enjoy what they are doing here.” [P645]

Addressing these aspects can lead to a more positive and motivating work environment, ultimately contributing to higher satisfaction among software practitioners.

Personal productivity. Personal productivity was highlighted by some practitioners, particularly the desire to improve Technical mastery (4), which is a crucial factor for ensuring competence and confidence. Other factors included Perceived productivity (3) and the ability to achieve goals (2), which refer to achieving goals and considering themselves productive within the company [29]. One respondent cited feeling like an important member of one’s team (1).

Organization. Within the organization category, Culture (6) was the most mentioned factor, followed by Vision (3) and a sense of Justice (1). Culture and vision highlight the importance of a positive and supportive work environment that aligns with the employees’ values and fosters collaboration and innovation [3]. Justice underscores the need for fair treatment and equity within the workplace, ensuring that all employees feel respected and valued [14]. \(P_{32}\), for example, mentioned:

“Have a broader view of the department’s performance in the global context of the organization.” [P32]

Technical Factors

The close-ended questions did not initially foresee the answers in this category. However, some participants also pointed out the need for technical improvement. These resources can also impact job satisfaction and productivity [3, 12]. We also coded responses in the processes and systems category as hardware (31), tools (14), and processes (13) factors. Some practitioners were concerned with access to better and more up-to-date equipment and tools. As an example, \(P_{640}\) mentioned (see Table 3):

“I would improve the work tool; the computer is obsolete in relation to the software needed for working. It is necessary to upgrade the machine for better performance.” [P640]

Follow-Up Meetings with Company Practitioners

We conducted several meetings with practitioners to validate the interpretation of results using their feedback based on their experience with the company. Additionally, one practitioner actively participated in the coding process, playing a crucial role in ensuring the accuracy of our findings. Their experience proved crucial in accurately understanding the results. For example, they identified that participants’ reluctance to recommend their team to a friend (as discussed in RQ3 in Section RQ3—How Satisfied are the Team Members with Their Teams?) stemmed from issues related to the type of work, such as dealing with obsolete technology, legacy systems, and bureaucratic workflows.

During these discussions, we presented the coded factors and collaborated on interpreting the findings.

Discussion

This study assesses work engagement and job satisfaction by software professionals working remotely in a large governmental software organization. This section provides a comprehensive analysis of the study’s findings by revisiting the research questions, exploring the relationships between the open-ended and closed questions, and identifying additional factors that impact job satisfaction.

Figure 4 summarizes the survey results. For this, we were inspired by evidence briefings used to disseminate research findings to practitioners [38]. Instead of using a one-page document to transfer knowledge acquired from empirical studies, we present an overview of the main results obtained from the survey to synthesize our findings.

First, we revisit each research question: RQ1 discusses the high levels of work engagement among the teams, highlighting the strong sense of energy, enthusiasm, and immersion reported by practitioners; RQ2 addresses the positive assessment of psychological safety, team effectiveness, performance, task allocation, and career development, noting areas of strength and opportunities for improvement; RQ3 examines team satisfaction; and RQ4 details the findings from the qualitative analysis. Next, we explore the alignment between open-ended and closed questions, identifying areas where qualitative feedback provides deeper insights into quantitative results. We also address additional factors that emerged as significant influences on job satisfaction. Finally, we compare our findings with related work, situating the results within broader software development team dynamics and identifying similarities and differences with existing literature.

Revisiting the Research Questions

RQ1—How is the Work Engagement in the Teams?

The work engagement within the teams appears quite strong. Our findings (Fig. 2) indicate that most participants reported high levels of energy, enthusiasm, pride, and involvement in their work, suggesting deep engagement and connection with their tasks. Overall, the results reflect a consistently high level of work engagement among the teams.

These findings suggest a strong connection with their work, characterized by vigor, dedication, and concentration, which likely reduces the chances of absenteeism and employee turnover. It also reflects a sense of significance, inspiration, and pride in their roles. In particular, none of the participants reported “Never” for feeling immersed, and only 1% selected this response for feelings of energy, enthusiasm, pride, and the perception of time passing quickly.

RQ2—How do the Teams Assess the Dimensions of Psychological Safety, Team Effectiveness, Performance, Allocation, and Career Development?

The results reveal how the teams generally assess their work environment across the dimensions of psychological safety, team effectiveness, performance, allocation, and career development. Regarding psychological safety, the results indicate that most software practitioners feel a strong sense of psychological safety. However, some extent only occasionally or rarely experience this safety, suggesting that the company should work to ensure that everyone consistently feels safe to express themselves.

Considering team effectiveness and performance, respondents view their teams as effective and feel they have good autonomy in projects. Satisfaction with overall team performance is high.

There are mixed perceptions for task allocation and career development dimensions, suggesting some teams struggle with workload distribution. In terms of career development, experiences vary widely. Our findings underline the importance of consistent feedback and career development opportunities for team members.

The results of RQ2 highlight several key insights into how the teams assess these dimensions.

RQ3—How Satisfied are the Team Members with Their Teams?

Our findings indicate while the majority sentiment is favorable, with over half expressing satisfaction, the presence of neutral and negative responses suggests that some practitioners face challenges or dissatisfaction that could affect their willingness to endorse their team.

RQ4—What Factors can be Improved in the Work Environment?

Respondents expressed broader concerns when answering the open question. Team dynamics, encompassing collaboration, communication, and psychological safety, received considerable attention. Communication and Collaboration were the most frequently highlighted. This suggests that software practitioners highly value effective communication and teamwork, indicating a need for stronger collaboration and better communication channels within teams.

Management factors, including feedback, autonomy, and leadership quality, emerged as significant areas for improvement. Work-life balance, stress management, and opportunities for career growth were highlighted. Additionally, respondents emphasized the need for advanced technical training and a more supportive work environment, including remote work options and physical workspace considerations.

Regarding technical aspects, the respondents also emphasized technical factors, indicating that hardware, tools, and processes can also impact job satisfaction and productivity.

Relating the Open-Ended and Closed Questions

Despite the high level of engagement and satisfaction observed in the self-reported questionnaire, we found significant factors reported as impacting employee satisfaction after coding the open-ended responses to RQ4 (see Section RQ4—What Factors can be Improved in the Work Environment?). We compared the open-ended responses with the closed-ended responses of each participant.

About psychological safety (Q7), for example, 24% only occasionally or rarely experience safety. Additionally, open-ended responses also highlighted the importance of psychological safety. This indicates that despite the positive evaluation of psychological safety in the self-reported questionnaire, its perceived presence varies slightly between teams, with some practitioners calling for more attention to this dimension.

In both surveys, communication within teams was generally rated positively (Q9) with 88% of total respondents acknowledging proactive communication. Still, the responses to the open-ended question indicate that practitioners see opportunities for improvement. Notably, communication emerged as the most frequently mentioned isolated factor in the open question being referred to by 49 respondents.

Regarding the allocation of activities within the team (Q15), when comparing the questionnaire results and open questions, 34% notice balance only occasionally or rarely. This suggests some teams are struggling with workload distribution. Practitioners also highlighted team size and specifically mentioned allocation as areas needing improvement in the open questions. These findings suggest a growing recognition of workload distribution challenges.

Comparing the factors mentioned in the open questions and the responses to the closed questionnaire in the Management category also reveals some interesting insights. In the closed Question (Q18): 59% of respondents (answered “frequently,” “almost always,” or “always”) feel appreciated by their managers, while 19% rarely or never experience this recognition. While most practitioners feel appreciated, the mention of appreciation in the open questions suggests that those who do not feel appreciated may be particularly vocal about it. Regarding autonomy (Q11), 61% of respondents feel they have a good degree of autonomy in their projects, while 12% rarely or never experience autonomy. The mentions in the open questions and the closed question results indicate that while many practitioners value and experience autonomy, it remains a critical area for those who feel it is lacking. The importance of feedback is clearly reflected in both the open and closed questions. Despite a majority receiving feedback, the open responses mention that the quality or frequency of feedback might still be a concern for a considerable portion of practitioners. Management is also a key concern, which aligns with the mixed responses regarding career development discussions in the closed questions.

Thus, the open-ended question, asking the participants what they would do with a magic wand (Q20), encouraged the creativity and critical thinking of the respondents. The answers reveal underlying concerns that the closed questions may not fully capture. It highlights areas where practitioners feel the need for improvements, particularly in management practices, feedback, team dynamics, rewards, benefits, career, and work-life balance. Therefore, this question allowed a deeper understanding of the aspects evaluated in the survey and the surfacing of ideas not initially foreseen in the closed questions.

Additional Factors Impacting Job Satisfaction

When we coded the open answers to the survey, we considered the categories proposed by [3] and [14] as an extensive list of factors impacting satisfaction and productivity. However, the survey respondents mentioned additional factors not considered by [3] and [14] as necessary to job satisfaction. Following, we discuss these findings.

Meeting planning. We added this factor to the management category. Participants mentioned the need for better planning and organization of meetings. Improper meeting planning can be a waste of time and a challenge for developers [28, 35], potentially impacting productivity.

Social interactions. It is another factor that emerged in our analysis. We added this factor to the team category. Respondents wanted more interactions, events, and social connections between team members. Missing social interactions can affect connection and interpersonal communication with team members, impacting developers’ productivity [36].

Allocation. This factor emerged in our analysis of the second group. Nine practitioners mentioned the need to balance the distribution of activities and responsibilities to not overload specific team members. Although [14] considered the team size factor, they did not directly address allocating tasks within the team. Thus, we coded the answers in this additional factor in the Project category.

Remote working. This factor also emerged in our analysis of the second group. We coded it in the work environment category. Eleven practitioners mentioned this factor in their answers. While other researchers reported a considerable negative impact on practitioners’ well-being, satisfaction, and productivity [18,19,20], the survey respondents emphasized the benefits of working remotely and wanted to maintain this working model.

Empathy. This factor also emerged in our analysis of the second survey. It is the ability to understand other people’s emotions, feelings, and perspectives [34]. We coded this factor in the team category. Six answers mentioned this factor. Practitioners cited the need to practice empathy in their teams to improve communication, collaboration, and relationships within the team. It is one of the factors influencing software development activities [34].

In our first analysis, we added meeting planning and social interactions to the list of factors that can impact job satisfaction. In the second analysis, we also found these factors, but we included three additional factors: allocation, remote working, and empathy. We recommend that these factors should be considered in future works addressing the job satisfaction of software practitioners.

Factors Emerging from the Second Phase of the Study

When comparing the answers to the open questions, it is important to notice that some factors emerged when surveying the participants from the study’s second phase. As previously discussed, the difference between the two phases of the study regards the number of participants and their role in the company. In the first phase, we surveyed 148 respondents acting as software architects, designers, and process analysts; in the second phase, 743 respondents acted as requirement analysts and software developers. Thus, the emergence of new factors might relate to the higher number of participants or the difference in their roles. Despite this study not addressing the difference in the participant’s roles in the company, the emergence of new factors suggests that the different profiles of practitioners surveyed may have influenced these results. Thus, we highlight these differences.

For instance, all forty appearances of the Manager (Table 4) factor in the Management category spring up from the participant’s perceptions of the second survey. The significant focus on the manager in the second group might indicate that they emphasize leadership and management styles. This could be due to differences in management practices or the level of managerial support experienced by the practitioners in this group.

Some factors emerging are related to lifestyle and mental health. We highlight the factors of Work-Life Balance, Stress, and Happiness, with zero mentions in the first survey. This might suggest distinct concerns and priorities among the two groups. The appearance of Work-Life Balance and Stress suggests that the second group is more concerned with balancing their professional and personal lives and the stress associated with their work. This could be influenced by the nature of their work, workload, or even the stage of their careers. The mention of Happiness might indicate that the second group of practitioners may be more attuned to their overall well-being and job satisfaction. This focus might be driven by a broader view of job satisfaction, including emotional well-being, which could vary depending on the team’s culture or organizational environment.

Another aspect regards categories related to the work environment and team organization. For example, the emergence of factors like Camaraderie, Empathy, and Team Cohesion in the second survey could indicate that the second group emphasizes interpersonal relationships and team bonding more. These differences might be attributed to variations in team dynamics, organizational culture, or the specific challenges faced by the different groups of practitioners. It can also be related to the group receiving training in soft skills and work-life balance, which may have heightened their awareness of these themes.

They likely reflect the unique work environments, organizational cultures, and personal priorities of the practitioners in the second group, highlighting how practitioner profiles can significantly impact the factors they prioritize or are concerned about in their work environment. They also underscore the importance of understanding different teams’ unique contexts and priorities, which can vary based on factors such as project type, team size, leadership styles, or even the teams’ maturity level.

These assumptions highlight the importance of running the survey with different teams and participants to produce insights that can help the company promote continuous improvement in practitioners’ engagement and satisfaction. These insights will be further investigated to broaden the evaluation of the differences in the practitioner’s perceptions comparing software engineers and developers. For completeness, Appendix 8 independently details the number of factors considering the two applied surveys.

Implications for Practitioners and Researchers

Our findings provided managers with relevant information about the engagement and satisfaction of employees within the organization. Based on our findings, they could focus on factors that present room for growth and also reinforce the positive factors discussed by the respondents. We also provide tools for diagnosing and continuously improving the organizational environment. The success rate of survey participation also reflects the study’s careful design and planning. Both the research strategy and the findings of our work can be helpful for software companies to evaluate and improve work engagement and job satisfaction within their teams.

According to the most commonly mentioned factors to improve practitioners’ engagement and job satisfaction, we summarized a list of actionable insights in a cheat sheet presented in Fig. 5. These insights can help software organizations influence practitioners’ productivity by improving their work engagement and job satisfaction.

The differences between the two groups indicate that employees can be influenced by the nature of the work, workload, and career stage to have an opinion regarding their work. Software companies can consider these factors to provide an environment that enables work engagement and job satisfaction. Simply knowing how employees feel about work is insufficient to arrive in this enabling environment.

For researchers, the results presented in our work have been explored little, and there is still a gap for further investigation. Our survey appointed new factors (meeting planning, social interactions, allocation, remote working and empathy) impacting software practitioners satisfaction, representing a contribution for researchers and pointing a gap for further investigation.

We also highlight using NPS to measure team members’ satisfaction with their teams (see “Survey Instrument”). Despite growing popularity among practitioners, NPS faces some criticism from academics [39]. Even so, [39] emphasizes the value of academic partnership with practitioners to achieve relevant and robust research on using NPS. Our survey shows how it can be used to assess practitioners’ satisfaction with their teams.

Our survey can be considered viable for future research. Researchers can use it to test the same constructs in different settings and with various target groups, enabling comparisons with the findings of this study.

Another important aspect of our study is the partnership between the software industry and academia since field research addressing human factors in the software industry is still rising, especially in developing countries [11].

Threats to Validity

We evaluated the threats to the validity of our study using established guidelines [40]. There are some threats to the validity of this work, as with any other empirical study. Below, we discuss the most relevant threats to our study.

Conclusion validity. It affects the capacity to interpret the results correctly. A threat arises from the qualitative analysis because it is subjective and subject to inconsistencies. We used this analysis to answer RQ4. The researchers individually analyzed and coded all open-ended questions to mitigate this threat. Later, they compared and refined their results until reaching a consensus. Finally, we presented the results of the qualitative analysis and discussed them with the company practitioners for validation.

Construct validity. Overall, participants may, based on the fact that they are part of a study, act differently than they do otherwise. To help prevent hypothesis guessing and evaluation apprehension, in the invitation e-mail, we clearly explained the purpose of the study and asked the participants to answer questions based on their own experiences. The questionnaire was anonymous, and the collected data was analyzed without considering the participants’ identities.

Internal validity. As the survey questions were answered remotely, the participants could misunderstand them, causing an internal threat to our study. To mitigate this, the survey was passed through internal reviews conducted by experienced researchers. Afterward, we piloted the survey with 79 employees to assess the survey questions, structure, and duration. We decided to shorten the questionnaire after the pilot study was validated.

External validity. The company we studied employs around 7,700 people working on software products for the government. Our results likely generalize more to the context of large public software companies than to small, private, or open-source organizations. Hence, we do not claim that our results are generalizable for all contexts. However, an argument can be made that the ecological validity of the work [41], i.e., the extent to which these findings approximate other real-world scenarios, is likely to hold in other settings.

Concluding Remarks

Our study explores factors influencing work engagement and job satisfaction among software practitioners, particularly within the context of remote work during the pandemic at a large governmental software organization. In total, 891 software professionals answered the survey. While engagement and satisfaction are inherently subjective and can vary widely based on individual and organizational contexts, our findings highlight key aspects that complement existing research and expand the knowledge base on the subject. Given the limited studies that specifically focus on work engagement and job satisfaction of software professionals working remotely for large software companies, our work addresses a critical gap. Our insights serve as a foundation for future research to understand better the evolving work conditions and challenges software practitioners face in similar contexts.

In future work, we want to replicate the study internally to explore the changes in perceptions over time. We also intend to expand this work to other software organizations. Large-scale analyses and baseline comparisons will facilitate discovering emerging trends or themes not previously identified, offering a broader view of work engagement and job satisfaction issues in software engineering in general. An extensive knowledge base will allow us to significantly expand the framework of actionable insights for improving job satisfaction in software organizations shown in Fig. 5. We also propose a longitudinal study exploring the root causes of concerns regarding the factors mentioned, such as psychological safety and career development. The results of this longitudinal study might be used as input for other researchers, providing actionable solutions to address these gaps. Conducting longitudinal studies could capture changes in work engagement and satisfaction over time, particularly concerning remote work policies. Additionally, comparing remote, in-office, and hybrid work models could offer a clearer understanding of their effects on employee well-being. Finally, we propose expanding the survey to include demographic factors such as age, gender, role, and experience, as it may also reveal nuanced insights, enriching our understanding of how these elements shape work engagement and satisfaction.

Due to the required effort, the qualitative data analysis of this type of study remains challenging. We are exploring the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) to analyze the qualitative data from surveys using the coding framework established in the current study. Training the LLM on the existing codes and insights generated in this research allows one to fine-tune the model to recognize patterns and nuances in responses from different practitioner profiles or work environments. This approach will allow for the automated identification and categorization of themes across diverse datasets. It may also improve consistency in the qualitative analysis process.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data for this study is not publicly available due to company policy regarding confidentiality and data protection. However, summary data and relevant analysis results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Serpro is an acronym for Data Processing Federal Service (in Portuguese: Serviço Federal de Processamento de Dados).

The opinions expressed in this work reflect the authors’ viewpoint and do not necessarily correspond to the position of SERPRO on the presented subject.

Data extracted from SERPRO’s Transparency and Governance Portal.

We translated all answers quoted in this work from Portuguese.

The respondents’ assessment reflects their perception of their team, not the company.

References

Capretz LF. Bringing the human factor to software engineering. IEEE Softw. 2014;31(2):104.

Meyer AN, Fritz T, Murphy GC, Zimmermann T. Software developers’ perceptions of productivity. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Foundations of Software Engineering, 2014;pp. 19–29.

Storey M-A, Zimmermann T, Bird C, Czerwonka J, Murphy B, Kalliamvakou E. Towards a theory of software developer job satisfaction and perceived productivity. IEEE TSE. 2019;47(10):2125–42.

Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-Romá V, Bakker AB. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3:71–92.

Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Taris TW. Work engagement: an emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress. 2008;22(3):187–200.

Forsgren N, Storey M-A, Maddila C, Zimmermann T, Houck B, Butler J. The space of developer productivity: there’s more to it than you think. Queue. 2021;19(1):20–48.

Duhigg C. What google learned from its quest to build the perfect team. NY Times Mag. 2016;26(2016):2016.

Gavin DA. How Google sold its engineers on management. Harvard Business Review. 2013. https://hbr.org/2013/12/how-google-sold-its-engineers-on-management. Accessed 10 Jan 2025.

Harrel M, Barbato L. Great managers still matter: the evolution of Google’s Project Oxygen. 2018. https://www.oneworldconsulting.com/owc-articles-db-alt.php?id=126&d=tr. Accessed 10 Jan 2025.

StackOverflow: 2024 Stack Overflow Developer Survey. https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2024/. 2024. Accessed 10 Jan 2025.

França C, Da Silva FQ, Sharp H. Motivation and satisfaction of software engineers. IEEE TSE. 2018;46(2):118–40.

Canedo ED, Santos GA. Factors affecting software development productivity: an empirical study. In: 33rd SBES, 2019; pp. 307–316.

Razzaq A, Buckley J, Lai Q, Ting Y, Botterweck G. A systematic literature review on the influence of enhanced developer experience on developers’ productivity: factors, practices, and recommendations. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;57(1):1–46.

Wagner S, Ruhe M. A systematic review of productivity factors in software development. CoRR. 2018. arXiv: 1801.06475.

Panteli N, Yalabik ZY, Rapti A. Fostering work engagement in geographically-dispersed and asynchronous virtual teams. Inf. Tech. & People. West Linn. 2018;32(1):2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-04-2017-0133.

Cerqueira L, Nunes L, Malheiros V, Guerra R, Santana B, Spínola R, Mendonça M, Santos J. Software engineers engagement and job satisfaction: a survey with practitioners working remotely in a public organization. SciTePress, 2024; 65–76. https://doi.org/10.5220/0012676400003690. INSTICC.

Graziotin D, Fagerholm F, Wang X, Abrahamsson P. On the unhappiness of software developers. In: 21st Int Conf on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Eng, 2017; pp. 324–333.

Ralph P, Baltes S, Adisaputri G, Torkar R, Kovalenko V, Kalinowski M, Novielli N, Yoo S, Devroey X, Tan X, Zhou M, Turhan B, Hoda R, Hata H, Robles G, Milani Fard A, Alkadhi R. Pandemic programming: how COVID-19 affects software developers and how their organizations can help. Empir Softw Eng. 2020;25(6):4927–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-020-09875-y.

Silveira Neto PAdm, Mannan UA, Almeida ES, Nagappan N, Lo D, Singh Kochhar P, Gao C, Ahmed I. A deep dive into the impact of covid-19 on software development. IEEE Trans Softw Eng. 2022;48(9):3342–60. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2021.3088759.

Russo D, Hanel PH, Altnickel S, Berkel N. Satisfaction and performance of software developers during enforced work from home in the covid-19 pandemic. Empir Softw Eng. 2023;28(2):53.

Johnson B, Zimmermann T, Bird C. The effect of work environments on productivity and satisfaction of software engineers. IEEE TSE. 2019;47(4):736–57.

Bezerra CI, Souza Filho JC, Coutinho EF, Gama A, Ferreira AL, Andrade GL, Feitosa CE. How human and organizational factors influence software teams productivity in covid-19 pandemic: a Brazilian survey. In: 34th Brazilian Symp. on Software Eng, 2020; pp. 606–615.

Marinho M, Amorim L, Camara R, Oliveira BR, Sobral M, Sampaio S. Happier and further by going together: The importance of software team behaviour during the covid-19 pandemic. Technol Soc. 2021;67: 101799.

Tokdemir G. Software professionals during the covid-19 pandemic in turkey: factors affecting their mental well-being and work engagement in the home-based work setting. J Syst Softw. 2022;188: 111286.

Silveira P, Mannan UA, Almeida ES, Nagappan N, Lo D, Kochhar PS, Gao C, Ahmed I. A deep dive into the impact of covid-19 on software development. In IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, vol. 48, no. 9, pp. 3342–3360, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2021.3088759.

Neuber L, Englitz C, Schulte N, Forthmann B, Holling H. How work engagement relates to performance and absenteeism: a meta-analysis. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2022;31(2):292–315.

Edmondson AC, Lei Z. Psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu Rev Org Psychol Org Behav. 2014;1(1):23–43.