Abstract

Unlike neoclassical economics in which humans are typically described as self-interested, more and more social studies strongly support the notion that individuals derive utility not only from their own status, but also from comparisons with others. While prior studies have shown that relative income effects matter for optimal income taxation, most assumed either homogeneous relative income effects for the entire population, or relative income effects that differ only on the basis of whether one is above or below their comparison group. We investigate the importance of relative income effects within the context of an optimal income tax model with a broader form of heterogeneity. Specifically, we assume income-dependent relative income effects, which follow in the spirit of empirical evidence. Simulation results show that the optimal tax system becomes more progressive to the extent that the relatively wealthy have stronger concerns regarding others’ income than the relatively poor. This is an important result because it may provide theoretical evidence that increasing progressivity can be efficiency-enhancing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Peng (2017) used British data to show that the relative income effect falls as own income rises.

Corlett and Hague (1953) argued that the goods that are relatively more complementary to the untaxed good (leisure) should be applied to higher tax rates. A similar conclusion arises here in that the goods that are more complementary to the untaxed good (social status) should also have higher tax rates.

Aronsson and Johansson-Stenman (2010) is an exception that they incorporated asymmetry into a two-type OLG model.

These studies usually divided the population into two categories: one with income above the comparison group’s and another with income below. Two different relative income effects are assigned for those two categories. Upwards asymmetric relative income effects are confirmed if the effect of the category whose income is lower than the reference group’s is larger than the effect of the other.

Mayraz et al. (2009) and Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2005) found different results using the same dataset (GSOEP). The former let subjects choose the reference group themselves while the latter defined the reference group as all agents at a similar education level, in the same age bracket, and living in the same region.

This is due to incentive compatibility conditions: for any two individuals i and j, if \(w_i>w_j \), we can have \(w_i y_i >w_j y_j \) and \(x_i >x_j \). As a result, w is monotonically related to x.

For details, please see Appendix 2.

This implies that there is not a traditional revenue constraint in the sense that no pre-determined revenue requirement exists. Tax revenue is purely for redistribution purposes. This is equivalent to the notion that the government needs revenue to fulfill its goal of providing a basket of public goods and services, which are assumed to be equally valued by everyone.

Noted that Kanbur and Tuomala (2013) evaluated the case where \(\varphi \) is homogeneous and equal to 1. However, in the current study, to make a better and clearer comparison, we set the homogeneous \(\varphi \) equal to the population mean of case C (where agents have income-dependent relative income effects ranging from 0 to 1).

Some examples of the hourly wage levels accompanied by cumulative density functions are in the first two columns of Table 2.

Details are available online: http://www.aeaweb.org/jep/app/2304_Mankiw_Weinzierl_Yagan_ appendix.pdf. Accessed on 09 Feb 2018.

Substituting (10) into (9), the top marginal tax rate is \(\int \frac{x\varphi }{\mu \left( {1+\varphi } \right) }fdw\). It can be seen that with either symmetric or heterogeneous relative income effects, it is no longer be zero (as in Kanbur and Tuomala 2013) Also, the top MTR with symmetric relative income effects is different from that with heterogeneous relative income effects.

For the purpose of simplicity, the simulation results are not presented in the current study but is available upon request.

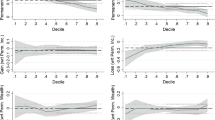

We re-run simualtions under a different utitliy specification where the Frisch labor supply elasticity is constant across the distribution. Generally, we find qualatively similar results that there is an increasing degree of progressivity in Case C compared with Cases A and B.

This lognormal distribution is fitted from the same dataset—March 2007, CPS.

In the spirit of several seminar papers in this area that discuss the possibility of upward comparison (e.g., Aronsson and Johansson-Stenman 2010), we have also done a simple experiment along this line in our setting. To be specific, we compare Case C from Fig. 5 with a new scenario that includes symmetric relative income effects (phi = 1), but where reference income is based on a representative wealthy agent (whose corresponding cdf is 80.05%). Results show that marginal tax rates are higher in this new scenario. This new tax schedule actually lies between Cases B and C.

China Luxury Goods Market Study, Bain & Company, 2013.

References

Akerlof GA (1978) Economics of tagging as applied to optimal income-tax, welfare program, and manpower-planning. Am Econ Rev 68(1):8–19

Alesina A, Ichino A, Karabarbounis L (2011) Gender-based taxation and the division of family chores. Am Econ J Econ Policy 3(2):1–40

Alpizar F, Carlsson F, Johansson-Stenman O (2005) How much do we care about absolute versus relative income and consumption? J Econ Behav Organ 56(3):405–21

Aronsson T, Johansson-Stenman O (2008) When the Joneses’ consumption hurts: optimal public good provision and nonlinear income taxation. J Public Econ 92(5–6):986–97

Aronsson T, Johansson-Stenman O (2010) Positional concerns in an OLG model: optimal labor and capital income taxation. Int Econ Rev 51(4):1071–1095

Aronsson T, Johansson-Stenman O (2013a) Conspicuous leisure: optimal income taxation when both relative consumption and relative leisure matter. Scand J Econ 115(1):155–175

Aronsson T, Johansson-Stenman O (2013b) Veblen’s theory of the leisure class revisited: implications for optimal income taxation. Soc Choice Welf 41(3):551–578

Aronsson T, Johansson-Stenman O (2015) Keeping up with the Joneses, the Smiths and the Tanakas: on international tax coordination and social comparisons. J Public Econ 131:71–86

Bos D, Tillmann G (1985) An envy tax—theoretical principles and applications to the German surcharge on the rich. Public Financ Finance Publiques 40(1):35–63

Boskin MJ, Sheshinski E (1978) Optimal re-distributive taxation when individual welfare depends upon relative income. Quart J Econ 92(4):589–601

Boyce CJ, Brown GDA, Moore SC (2010) Money and happiness: rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychol Sci 21(4):471–75

Clark AE, Oswald AJ (1996) Satisfaction and comparison income. J Public Econ 61(3):359–81

Corlett WJ, Hague DC (1953) Complementarity and the excess burden of taxation. Rev Econ Stud 21(1):21–30

Diamond PA (1998) Optimal income taxation: an example with a U-shaped pattern of optimal marginal tax rates. Am Econ Rev 88(1):83–95

Duesenberry James Stemble (1949) Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Easterlin RA (1995) Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all. J Econ Behav Organ 27(1):35–47

Easterlin RA (2001) Income and happiness: towards a unified theory. Econ J 111(473):465–84

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A (2005) Income and well-being: an empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. J Public Econ 89(5–6):997–1019

Fischbacher U, Schudy S, Teyssier S (2013) Heterogeneous reactions to heterogeneity in returns from public goods. Soc Choice Welf:1–23

Frank RH (2008) Should public policy respond to positional externalities? J Public Econ 92(8–9):1777–86

Ireland NJ (1998) Status-seeking, income taxation and efficiency. J Public Econ 70(1):99–113

Ireland NJ (2001) Optimal income tax in the presence of status effects. J Public Econ 81(2):193–212

Johansson-Stenman O, Carlsson F, Daruvala D (2002) Measuring future grandparents’ preferences for equality and relative standing. Econ J 112(479):362–83

Kanbur R, Tuomala M (2013) Relativity, inequality and optimal nonlinear income taxation. Int Econ Rev 54(4):1199–1217

Luttmer EFP (2005) Neighbors as negatives: relative earnings and well-being. Quart J Econ 120(3):963–1002

Mankiw NG, Weinzierl M (2010) The optimal taxation of height a case study of utilitarian income redistribution. Am Econ J Econ Policy 2(1):155–76

Mankiw NG, Weinzierl M, Yagan D (2009) Optimal taxation in theory and practice. J Econ Perspect 23(4):147–74

Mankiw NG, Weinzierl M, Yagan D (2009) Documentation of simulations. Optim Tax Theory Pract. http://www.aeaweb.org/jep/app/2304_Mankiw_Weinzierl_Yagan_appendix.pdf. Accessed on 09 Feb 2018

Mayraz Guy, Wagner Gert G, Schupp Jürgen (2009) Life satisfaction and relative income: perceptions and evidence. IZA Discussion Papers 4390, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)

McBride M (2001) Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. J Econ Behav Organ 45(3):251–78

Mccormick K (1983) Duesenberry and Veblen—the demonstration effect revisited. J Econ Issues 17(4):1125–29

Mirrlees JA (1971) Exploration in theory of optimum income taxation. Rev Econ Stud 38(114):175–208

Naimzada A, Sacco P, Sodini M (2013) Wealth-sensitive positional competition as a source of dynamic complexity in OLG models. Nonlinear Anal Real World Appl 14(1):1–13

Oswald AJ (1983) Altruism, jealousy and the theory of optimal non-linear taxation. J Public Econ 20(1):77–87

Peng L (2017) Estimating income-dependent relative income effects in the UK. Soc Indic Res 133(2):527–542

Sadka E (1976) Income-distribution, incentive effects and optimal income taxation. Rev Econ Stud 43(2):261–67

Saez E (2001) Using elasticities to derive optimal income tax rates. Rev Econ Stud 68(1):205–29

Seade JK (1977) Shape of optimal tax schedules. J Public Econ 7(2):203–35

Solnick SJ, Hemenway D (1998) Is more always better? A survey on positional concerns. J Econ Behav Organ 37(3):373–83

Solnick SJ, Hemenway D (2005) Are positional concerns stronger in some domains than in others? Am Econ Rev 95(2):147–51

Tran A, Zeckhauser R (2012) Rank as an inherent incentive: evidence from a field experiment. J Public Econ 96(9–10):645–50

Tuomala Matti (1990) Optimal income tax and redistribution. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Tversky A, Griffin D (1991) Endowment and contrast in judgments of well-being. In: Strack F, Argyle M, Schwartz N (eds) Subjective well-being: an interdisciplinary perspective, vol 21. Pergamon Press, Oxford, pp 101–118

Veblen T (1899) [1934] The theory of the leisure class. Modern Library, Random House, New York

Weinzierl M (2011) The surprising power of age-dependent taxes. Rev Econ Stud 78(4):1490–518

Acknowledgements

We thank Celeste Carruthers, Matthew Harris, Jacob LaRiviere, LeAnn Luna, Matthew Murray, William Neilson, Casey Rothschild, Rudy Santore, Adrienne Sudbury, Christian Vossler, Marianne Wanamaker, participants in the University of Tennessee Economics Brown Bag Workshop and the 2014 National Tax Association Annual Conference on Taxation, the associate editor and two anonymous referees for valuable suggestions. This project is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71603273).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Given that

Take derivative w.r.t. \(w_i \), we’ll have:

Given that

and

Individual i chooses his/her labor supply \(y_i \) to maximize own utility:

Still start with (3), take derivative w.r.t. \(w_i \) gives us:

Substitute (A1) and (A3) into (A4) gives us the incentive compatibility condition:

Following Kanbur and Tuomala (2013), it is easier to think of government as choosing \(x_i \), \(y_i \) and \(\mu \) to maximize the utilitarian social welfare function (5). First, we invert the utility function and it gives us:

Calculating derivatives based on (3):

The government is maximizing (5) subject to conditions (1), (6), and (7). Their Lagrangian multipliers are \(\gamma \), \(\lambda \), and \(\alpha \left( w \right) \), respectively. After integrating by parts, the Lagrangian becomes (dropping i thereafter):

The first order conditions are:

Traditional transversality conditions are satisfied:

Integrating (A11) gives us:

Re-arrange (A3) we can get:

Substitute (A15) into (A12), we have:

Re-arrange (A17) we can get:

Substitute (A16) and (8) into (A18) and rearrange:

where (A13) indicates that \(\frac{\gamma }{\lambda }=\frac{ {\int _{\underline{w}}^{\bar{w}}} h_\mu fdw}{1- {\int _{\underline{w}}^{\bar{w}}} h_\mu fdw}\).

Appendix 2

For agent i, recall that the utility function is as follows:

The Frisch Elasticity of labor supply holds the marginal utility of consumption constant. Following the traditional setting, regarding our utility specification, the FOCs (omitting all i thereafter) are:

where \({\zeta }\) is the multiplier of the budget constraint for the individual.

Combing (A19) and (A20), we have the Frisch Elasticity of labor supply \(\eta ^{\upzeta }\):

Hoding everthing else constant, clearly low-skill jobs have larger elasticities. As either w or \(\varphi \) increases, \(\eta ^{\upzeta }\) decreases. Agents with large relative concerns or high wage levels are less elastic: taxing them more heavily does not reduce labor supply much and causes relatively small efficiency loss.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bruce, D., Peng, L. Optimal taxation in the presence of income-dependent relative income effects. Soc Choice Welf 51, 313–335 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-018-1118-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-018-1118-4