Abstract

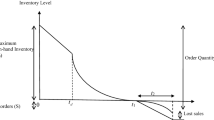

An optimal dynamic pricing strategy for non-instantaneous deteriorating items exhausted in a sales period without replenishment is explicitly characterized. Originally, the inventory level of the items reduces simply as a result of customer demand, and subsequently decreases owing to both demand and deterioration. This paper formulates a dynamic pricing model to maximize the enterprise’s profit. The optimal dynamic pricing strategy is obtained by solving the optimization problem based on Pontryagin’s maximum principle. Two static pricing models, including a uniform pricing model and a two-stage pricing model, are carried out to compare with the dynamic pricing model to show the significant advantage of the dynamic strategy. Furthermore, numerical examples, together with sensitivity analysis of the optimal solution with respect to major parameters, are provided to illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Balkhi, Z. (2011). Optimal economic ordering strategy with deteriorating items under different supplier trade credits for finite horizon case. International Journal of Production Economics, 133(1), 216–223.

Bitran, G., & Caldentey, R. (2003). An overview of pricing models for revenue management. Manufacturing Service Operations Management, 5(3), 203–229.

Cao, P., Li, J., & Yan, H. (2012). Optimal dynamic pricing of inventories with stochastic demand and discounted criterion. European Journal of Operational Research, 217(3), 580–588.

Chan, L. M., Shen, Z. M., Simchi-Levi, D., & Swann, J. L. (2004). Coordination of pricing and inventory decisions: A survey and classification. In D. Simchi-Levi, S. D. Wu, & Z. J. M. Shen (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative supply chain analysis: Modeling in the e-business era (pp. 335–392). Boston: Kluwer.

Chang, C. T., Teng, J. T., & Goyal, S. K. (2010). Optimal replenishment policies for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with stock-dependent demand. International Journal of Production Economics, 123(1), 62–68.

Chang, H. J., Teng, J. T., Ouyang, L. Y., & Dye, C. Y. (2006). Retailers optimal pricing and lot-sizing policies for deteriorating items with partial backlogging. European Journal of Operational Research, 168(1), 51–64.

Chatwin, R. E. (2000). Optimal dynamic pricing of perishable products with stochastic demand and a finite set of prices. European Journal of Operational Research, 125(1), 149–174.

Chung, K. J. (2009). A complete proof on the solution procedure for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with permissible delay in payment. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 56(1), 267–273.

Covert, R. P., & Philip, G. C. (1973). An EOQ model for items with Weibull distribution deterioration. AIIE Transaction, 5(4), 323–326.

Dye, C. Y., Ouyang, L. Y., & Hsieh, T. P. (2007). Inventory and pricing strategies for deteriorating items with shortages: A discounted cash flow approach. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 52(1), 29–40.

Elmaghraby, W., & Keskinocak, P. (2003). Dynamic pricing in the presence of inventory considerations: Research overview, current practices, and future directions. Management Science, 49(10), 1287–1309.

Feng, Y., & Xiao, B. (2000). A continuous-time yield management model with multiple prices and reversible price changes. Management Science, 46(5), 644–657.

Gallego, G., & Ryzin, G. V. (1994). Optimal dynamic pricing of inventories with stochastic demand over finite horizons. Management Science, 40(8), 999–1020.

García-Crespo, Á., Ruiz-Mezcua, B., López-Cuadrado, J. L., & González-Carrasco, I. (2011). A review of conventional and knowledge based systems for machining price quotation. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 22(6), 823–841.

Geetha, K. V., & Uthayakumar, R. (2010). Economic design of an inventory strategy for non-instantaneous deteriorating items under permissible delay in payments. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 233(10), 2492–2505.

Ghare, P. M., & Schrader, G. H. (1963). A model for exponentially decaying inventory system. International Journal of Production Research, 21, 449–460.

Goyal, S. K., & Giri, B. C. (2001). Recent trends in modeling of deteriorating inventory. European Journal of Operational Research, 134(1), 1–16.

Han, S., Oh, Y., & Hwang, H. (2012). Retailing policy for perishable item sold from two bins with mixed issuing policy. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 23(6), 2215–2226.

Hong, K. S., Yeo, S. S., Kim, H. J., Chew, E. P., & Lee, C. (2012). Integrated inventory and transportation decision for ubiquitous supply chain management. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 23(4), 977–988.

Ito, T., & Abadi, S. M. J. (2002). Agent-based material handling and inventory planning in warehouse. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 13(3), 201–210.

Kébé, S., Sbihi, N., & Penz, B. (2012). A Lagrangean heuristic for a two-echelon storage capacitated lot-sizing problem. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 23(6), 2477–2483.

Kincaid, W. M., & Darling, D. A. (1963). An inventory pricing problem. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Application, 7, 183–208.

Maihami, R., & Nakhai, Kamalabadi I. (2012). Joint pricing and inventory control for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with partial backlogging and time and price dependent demand. International Journal of Production Economics, 136(1), 116–122.

Manna, S. K., Lee, C. C., & Chiang, C. (2009). EOQ model for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with time-varying demand and partial backlogging. International Journal of Industrial and Systems Engineering, 4(3), 241–254.

Ouyang, L. Y., Wu, K. S., & Yang, C. T. (2006). A study on an inventory model for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with permissible delay in payments. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 51(4), 637–651.

Philip, G. C. (1974). A generalized EOQ model for items with Weibull distribution. AIIE Transaction, 6(2), 159–162.

Sen, A. (2012). A comparison of fixed and dynamic pricing policies in revenue management. Omega-International Journal of Management Science, 41(3), 586–597.

Shah, N. H., Soni, H. N., & Patel, K. A. (2012). Optimizing inventory and marketing policy for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with generalized type deterioration and holding cost rates. Omega-International Journal of Management Science, 41(2), 421–430.

Sonia, H. N., & Patelb, K. A. (2012). Optimal pricing and inventory policies for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with permissible delay in payment: Fuzzy expected value model. International Journal of Industrial Engineering, 3, 281–300.

Sugapriya, C., & Jeyaraman, K. (2008). Determining a common production cycle time for an EPQ model for non-instantaneous deteriorating items allowing price discount using permissible delay in payments. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 3(2), 26–30.

Tadikamalla, P. R. (1978). An EOQ inventory model for items with gamma distributed deterioration. AIIE Transactions, 10(1), 100–103.

Wu, K. S., Ouyang, L. Y., & Yang, C. T. (2006). An optimal replenishment policy for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with stock-dependent demand and partial backlogging. International Journal of Production Economics, 101(2), 369–384.

Wu, K. S., Ouyang, L. Y., & Yang, C. T. (2009). Coordinating replenishment and pricing policies for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with price-sensitive demand. International Journal of Systems Science, 40(12), 1273–1281.

Yang, C. T., Ouyang, L. Y., & Wu, H. H. (2009). Retailer’s optimal pricing and ordering policies for non-instantaneous deteriorating items with price-dependent demand and partial backlogging. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2009, Article ID 198305.

Yano, C. A., & Gilbert, S. M. (2005). Coordinated pricing and production/procurement decisions: A review. Managing Business Interfaces. Springer US, 16, 65–103.

Yassine, A. A. (2012). Parametric design adaptation for competitive products. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 23(3), 541–559.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments, which have brought about an excellent improvement in the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China No. 61004015, the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in Universities of China No. NCET-11-0377, and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University of China No. IRT1028.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Proof

As for Case 1, if \(\lambda (0)\ge -\frac{\alpha }{\beta }\), which yields \(h\le \frac{\alpha \theta }{\beta }\frac{1+{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}}{1-{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}+\theta t_{d}}\) known from (11), the optimal pricing strategy is shown as

Substituting (35) into (1), one can obtain the inventory with \(I(0)=I_{0}\) as

where

To satisfy \(I(T)=0, T\) should meet the condition shown in (16).

As for Case 2, if \(\lambda (t_{d})\ge -\frac{\alpha }{\beta }\) and \(\lambda (0)<-\frac{\alpha }{\beta }\), which yield \(\frac{\alpha \theta }{\beta }\frac{1+{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}}{1-{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}+\theta t_{d}}<h\le \frac{\alpha \theta }{\beta }\frac{1+{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}}{1-{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}} \) known from (11), the optimal pricing strategy is shown as

where \(t_{1}=t_{d}-\displaystyle \frac{1}{h}\left( N+M{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}\right) \) derived from \(\lambda (t_{1})=-\displaystyle \frac{\alpha }{\beta }\).

By virtue of (1), (37) and \(I(0)=I_{0}\), the inventory is given by

where

and

With \(I_{2}(T)=0, T\) should satisfy Eq. (18).

As for Case 3, if \(\lambda (t_{d})<-\frac{\alpha }{\beta }\), which yields \(h>\frac{\alpha \theta }{\beta }\frac{1+{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}}{1-{e}^{\theta (t_{d}-T)}}\) known from (11), the optimal pricing strategy is shown as

where \(t_{2}=T+\frac{1}{\theta }\ln (-\frac{N}{M})\) derives from \(\lambda (t_{2})=-\frac{\alpha }{\beta }\).

According to (1) and \(I(0)=I_{0}\), the inventory is given by

where

and

To satisfy \(I(T)=0, T\) should meet the condition shown in (20).

As for Case 4, if \(\lambda (0)\ge -\frac{\alpha }{\beta }\), which is equivalent to \(h\le \frac{2\alpha }{\beta T}\) known from (15), the pricing strategy is shown as

With \(I(0)=I_{0}\), the inventory is consequently given by

Note that \(I(T)=0. T\) should meet the condition shown in (22), making \(h\le \frac{2\alpha }{\beta T}\), i.e., \(h\le \frac{\alpha ^{2}}{\beta I_{0}}\).

As for Case 5, if \(\lambda (0)<-\frac{\alpha }{\beta }\), which yields \(h>\frac{2\alpha }{\beta T}\) known from (15), the pricing strategy is shown as

where \(t_{3}=T-\displaystyle \frac{2\alpha }{h\beta }\).

Considered \(I(0)=I_{0}\), it follows that

Further, to satisfy \(I(T)=0, T\) should meet the condition shown in (24), making \(h>\frac{2\alpha }{\beta T}\), i.e., \(h>\frac{\alpha ^{2}}{\beta I_{0}}\). The proof is complete.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhang, J. & Tang, W. Dynamic pricing for non-instantaneous deteriorating items. J Intell Manuf 26, 629–640 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-013-0822-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-013-0822-2