Abstract

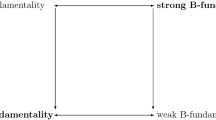

In a recent paper, Philip Kremer proposes a formal and theory-relative desideratum for theories of truth that is spelled out in terms of the notion of ‘no vicious reference’. Kremer’s Modified Gupta-Belnap Desideratum (MGBD) reads as follows: if theory of truth T dictates that there is no vicious reference in ground model M, then T should dictate that truth behaves like a classical concept in M. In this paper, we suggest an alternative desideratum (AD): if theory of truth T dictates that there is no vicious reference in ground model M, then T should dictate that all T-biconditionals are (strongly) assertible in M. We illustrate that MGBD and AD are not equivalent by means of a Generalized Strong Kleene theory of truth and we argue that AD is preferable over MGBD as a desideratum for theories of truth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

On page 348 of Kremer [9].

A T-biconditional, or, in Gupta’s words, a Tarski biconditional, is a sentence of form \(T(\bar {\sigma })\leftrightarrow \sigma \), with \(\bar {\sigma }\) a closed term which denotes \(\sigma \).

Modulo our use of assertible and deniable instead of true and false, which better fits in with the rest of the paper.

Note that the identity of truth differs from the intersubstitutability of truth, according to which \(T(\overline {\sigma })\) and \(\sigma \) are interchangeable in every (non opaque) context. In particular, revision theories of truth respects the identity of truth but not its intersubstitutability.

We assume familiarity with the notion of a (three valued) Strong Kleene fixed point valuation over M. To be sure, such a valuation has a Strong Kleene semantics, and it respects the world and the identity of truth. Further, we assume that such a theory valuates sentences of form \(T(c)\), where \(I(c) \not \in Sen(L_T)\) as d.

Which we use here as synonymous with ‘element of \(\mathbf {FP}_{M}\)’.

Thus, we have that \(SAP(\mathcal {K}) = SAP(\mathcal {K}^+) = \{ \mathbf {a}, \mathbf {d} \}, SAP(\mathcal {K}^{\mathbf {5}}) = \{\mathbf {a}_g, \mathbf {a}_i, \mathbf {d}_g, \mathbf {d}_i \}\).

LP abbreviates Logic of Paradox.

In every ground model in which there is a sentence that is valuated as u, the T-biconditional of \(\sigma \) is valuated as u and so not strongly assertible.

The notion of an X-neutral ground model originates with [5].

As argued by Kremer, his results put doubt on Gupta and Belnap’s claim that revision theories of truth have, as a distinctive general advantage over fixed point theories, their ‘…consequence that truth behaves like an ordinary classical concept under certain conditions—conditions that roughly can be characterized as those in which there is no vicious reference in the language.’ ([6] p. 201). As the claim of Gupta and Belnap is cast in terms of the intuitive theory-neutral notion of no vicious reference, Kremer’s results cannot be said to falsify their claim.

Kremer [8] gives an elegant proof (Theorem 4.21, 2.iv) which establishes a more general result. Given some very weak conditions on a partial function \(\mathcal {F}\), defined on hypotheses—potential significations of the truth predicate—the maximal intrinsic fixed point theory associated with \(\mathcal {F}\) satisfies MGBD. As the partial functions associated with each of the five schemas considered by Kremer satisfy the mentioned conditions, the associated maximal intrinsic fixed point theories all satisfy MGBD.

In a similar vein, it may also be possible for \(\textbf {T}^{\#}\), the revision theory of truth which violates MGBD and AD, to hedge against a violation of AD by buying protection from \(\textbf {T}^{*}\), which satisfies MGBD. However, as we are not interested in “saving \(\textbf {T}^{\#}\)” from the violation of any desideratum in the first place, we do not pursue these matters.

See Section 4.2 for another way.

We do not enter the discussion of whether it is more appropriate to ascribe truth to, say, propositions. Nothing substantial will hinge on the assumption that the truth-bearers are sentences.

Note that Kremer’s results (cf. Theorem 1) depend on the assumption that each of the thirteen theories of truth valuates truth ascriptions to non-sentential objects as (in our terms) a or d (Kremer naturally assumes the latter).

In fact, their argument pertains to any Strong Kleene fixed point valuation.

In fact, a consequence of the assumption that names are rigid designators is that our agent in fact knows all true identity statments, for example ‘Hespherus = Phosphorus’. The latter is a byproduct of the chosen formal model which may be ”repaired”, but such a repair would take us too far afield.

The assumption that our non-omniscient agent knows all details of sentential reference (secured via condition 2 and 3 of a NOA model) is clearly an idealization, but, we take it, a sensible one. Moreover, the assumption is a crucial one, as we explain in footnote 23.

Observe that, by following the same recipe of the definition \(\mathcal {V}^{\star }\) in terms of \(\mathcal {K}^{\bf 5}\), we can define a NOA theory corresponding to an arbitrary theory of truth T that is defined over ground models.

Compare the remarks on category mistakes in Section 4.1. On such a view, the non-classicality of ‘snow is true’ is explained by the semantics of the truth predicate: the fact that the truth predicate is only properly applied to sentences explains that to attribute truth to snow is to make a mistake.

Observe that the proof of Lemma 1 relies on the assumption that our agent knows all details of sentential reference, which is secured via defining condition 2 (”names are rigid designators”) and defining condition 3 (”the extension of the sentential predicate symbols in \(SP_L\) is the same throughout all the ground models of a NOA model”) of a NOA model. Accordingly, our claim that \(\mathcal {V}^{\star }\) violates MGBD but satisfies AD relies on this assumption. To see this, consider a NOA model \( \mathcal {M} = \{ M_@, M_1 \}\), where \(M_@\) is a clean ground model with, for some unary predicate P, \(I_@(P) = \emptyset \). Let \(M_1\) be just like \(M_@\) except that \(I_1(P) = \{ \forall x P(x) \rightarrow \neg T(x) \}\). Now clearly, \(\mathcal {M}\) is ruled out by defining condition 3 of a NOA model. However, observe that i) There is no vicious reference in \(\mathcal {M}\) according to \(\mathcal {V}^{\star }\), ii) \(\mathcal {V}^{\star }_{\mathcal {M}}\) valuates \(\forall x P(x) \rightarrow \neg T(x)\) (which, from the perspective of \(M_1\), is ”a predicate version of the Liar”) as \(\textbf {n}\). Together, i) and ii) testify that, without the assumption that our agent knows all details of sentential reference, \(\mathcal {V}^{\star }\) neither satisfies MGBD nor AD.

The subsentences of \(\alpha \vee \beta \) and \(\alpha \wedge \beta \) are \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \), the subsentence of \(\neg \alpha \) is \(\alpha \) and the subsentences of \(\forall x \phi (x)\) and \(\exists x \phi (x)\) are contained in \(\{ \phi (c) \mid c \in \mathit {Con}(L_T) \} \).

As we assume a Strong Kleene interpretation of the logical connectives.

For some theories T, the violation of MGBD is dependent on ground model under consideration. For instance, \(\mathcal {S}\), the minimal fixed point theory based on the Supervaluation theory satisfies MGBD with respect to a clean ground model, as the reader may wish to verify. \(\mathcal {S}\) violates MGBD though, as shown in example 5.10 of [8].

Kremer also considers, on page 362, a reaction that is in line with ours: ‘So, despite the apparent absence of vicious reference, \(\forall x T(x) \vee \neg T(x)\) seems ungrounded in our intuitive sense.’

References

Brown, J. (2010). Knowledge and assertion. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, LXXXI, 549–566.

Coffman, E. (2011). Does knowledge secure warrant to assert? Philosophical Studies, 154, 285–300.

Field, H. (2008). Saving truth from paradox. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fitting, M. (1986). Notes on the mathematical aspects of kripke’s theory of truth. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 27, 75–88.

Gupta, A. (1982). Truth and paradox. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 11, 1–60.

Gupta, A., & Belnap, N. (1993). The revision theory of truth. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kremer, P. (2000). On the Semantics for languages with their own truth predicates. In A. Chapuis & A. Gupta (Eds.), Truth, defintion and circularity, (pp. 217–246) New Dehli: Indian Council of Philosophical Research.

Kremer, P. (2009). Comparing fixed-point and revision theories of truth. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 38, 363–403.

Kremer, P. (2010). How truth behaves when there’s no vicious reference. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 39, 345–367.

Kripke, S. (1975). Outline of a theory of truth. Journal of Philosophy, 72, 690–716.

MacFarlane, J. (2011). What is assertion? In Brown J., & Cappelen H. (Eds.) , Assertion, (pp. 79–96). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weiner, M. (2005). Must we know what we say? Philosophical Review, 114, 227–251.

Weiner, M. (2007). Norms of assertion. Philosophical Compass, 2, 187–195.

Wintein, S. (2012). Playing with truth (PhD thesis). Rotterdam: Optima Grafische Communicatie.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Harrie de Swart and Reinhard Muskens, under whose supervision this paper was written. Further, thanks to the audiences of PhDs in Logic III (Brussels, 2011) and Truth at Work (Paris, 2011) for helpful comments on presentations of earlier versions of this paper. Finally, I would like to thank an anonymous referee of this journal, whose insightful comments helped to improve this paper a lot.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wintein, S. Alternative Ways for Truth to Behave When There’s no Vicious Reference. J Philos Logic 43, 665–690 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-013-9285-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-013-9285-3