Abstract

Research on the determinants of scholarly productivity is flourishing, driven both by long-standing curiosity about its wide variation, and by recent concern over race and gender inequalities. Beyond standard structural and demographic determinants of research output, some studies point to the role of individual psychology. We contribute to scholarship on personality and productivity by showing not only that personality matters, but when and for whom. Using an original, representative study of faculty from one discipline, political science, we propose and test several hypotheses about the “Big Five” personality determinants of productivity, as gauged through counts of publications, H-index scores, and citations. Controlling for a large number of familiar determinants (e.g., race, gender, rank, and institutional incentives), we find that conscientiousness predicts productivity, but that its effects are conditioned by openness to experience. More precisely, we discover that these two personality traits have compensatory effects, such that openness to experience and conscientiousness each matter most in the absence of the other. In addition, personality has heterogeneous impacts on productivity across different contexts; conscientiousness more strongly affects scholarly output in research-oriented institutions, while collaboration reduces the penalty associated with lack of conscientiousness.

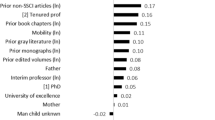

Source: PASS data for political science, 2017. Note: The figure shows 76% confidence intervals. Comparison of two 76% confidence intervals is equivalent to a 90% (p = .10, two-tailed) test of statistical significance at the point of overlap. Citations are logged

Source: PASS Data for Political Science, 2017. Note: The figure shows 76% confidence intervals. Comparison of two 76% confidence intervals is equivalent to a 90% (p = .10, two-tailed) test of statistical significance at the point of overlap. Citations are logged

Source: PASS Data for Political Science, 2017. Note: The figure shows 76% confidence intervals. Comparison of two 76% confidence intervals is equivalent to a 90% (p = .10, two-tailed) test of statistical significance at the point of overlap. Citations are logged

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In their analyses, Grosul and Feist (2014) do not include measures of such attributes as where one earned their doctoral degree, or the character of an individual’s current academic department.

In June, 2017 we conducted a companion study of sociology departments (at the same sampled universities). We discuss those results elsewhere (Djupe et al. 2019).

We had coders collect email addresses from the webpages for these departments. 44 email addresses were not usable.

Simon Hix graciously shared a list that went beyond what was reported in his paper, including 400 departments—this covered almost all of our sample.

We also attempted to replicate this procedure with Google Scholar, but discovered that a large portion of our respondents did not have public profiles there. SSCI counts are much lower than Scholar, but are highly correlated (Martín-Martín et al. 2018).

r(publications, H-index) = .81; r(publications, logged citations) = .71; r(logged citations, H-index) = .84.

The dependent variable for citations is estimated by adding one to the count, before logging. Hence, we exponentiate predicted values and subtract one to obtain predicted effects.

We do not find a statistically significant interaction between conscientiousness and any other personality variables beyond openness.

We obtain a similar pattern of results if we the model the average number of publications (dividing by years since PhD).

We thank Reviewer 1 for suggesting this direction of discussion and analysis.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context. Boulder: Westview Press.

Bakker, B. N., & Lelkes, Y. (2018). Selling ourselves short? How abbreviated measures of personality change the way we think about personality and politics. Journal of Politics,80(4), 1311–1325.

Blackburn, R. T., & Lawrence, J. H. (1995). Faculty at work. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Dion, M. L., Sumner, J. L., & Mitchell, S. M. (2018). Gendered citation patterns across political science and social science methodology fields. Political Analysis,26(July), 312–327.

Djupe, P. A. (2015). Peer reviewing in political science: New survey results. PS: Political Science and Politics, 48(2), 346–351.

Djupe, P. A., Smith, A. E., & Sokhey, A. E. (2019). Explaining gender in the journals: How submission practices affect publication patterns in political science. PS: Political Science and Politics,52(January), 71–77.

Ericsson, K. A. (1999). Creative expertise as superior reproducible performance: Innovative and flexible aspects of expert performance. Psychological Inquiry,10(4), 329–361.

Feist, G. J. (1998). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review,2(4), 290–309.

Feist, G. J. (2006). How development and personality influence scientific thought, interest, and achievement. Review of General Psychology,10(2), 163–182.

Feist, G. J. (2014). Psychometric studies of scientific talent and eminence. In D. K. Simonton (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of genius (pp. 62–86). Chichester: Wiley.

Feist, G. J. (2017). Creativity in the physical sciences. In J. C. Kaufman, V. P. Glaveanu, & J. Baer (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity across domains (pp. 199–225). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fox, M. F., & Milbourne, R. (1999). What determines research output of academic economists? Economic Record,75, 256–267.

Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the big-five factor structure. Psychological Assessment,4, 26–42.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the big five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality,37(December), 504–528.

Grosul, M., & Feist, G. J. (2014). The creative person in science. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts,8(1), 30–43.

Hattie, J., & Marsh, H. W. (2002). The relation between research productivity and teaching effectiveness. Journal of Higher Education,73(5), 603–641.

Hesli, V. L., & Lee, J. M. (2011). Why do some of our colleagues publish more than others? PS: Political Science and Politics,44(April), 393–408.

Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. PNAS,102(46), 16569–16572.

Hix, S. (2004). A global ranking of political science departments. Political Studies Review,2(3), 293–313.

John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality (pp. 114–158). New York: Guilford Press.

Kaufman, S. B., Quilty, L. C., Grazioplene, R. G., Hirsh, J. B., Gray, J. R., Peterson, J. B., et al. (2016). Openness to experience and intellect differentially predict creative achievement in the arts and sciences. Journal of Personality,84(April), 248–258.

King, M. M., Bergstrom, C. T., Correll, S. J., Jacquet, J., & West, J. D. (2017). Men set their own cites high: Gender and self-citation across fields and over time. Socius,3(January), 1–22.

Klingemann, H., Grofman, B., & Campagna, J. (1989). The political science 400: Citations by Ph.D. cohort and by Ph.D. granting institution. PS: Political Science and Politics,22(June), 258–270.

Knol, M. J., Pestman, W. R., & Grobbee, D. E. (2011). The (mis)use of overlap of confidence intervals to assess effect modification. European Journal of Epidemiology,26, 253–254.

MacGregor-Fors, I., & Payton, M. E. (2013). Contrasting diversity values: Statistical inferences based on overlapping confidence intervals. PLoS ONE,8(2), e56794.

Mahoney, M. J. (1979). Psychology of the scientist: An evaluative review. Social Studies of Science,9, 349–375.

Maliniak, D., Powers, R., & Walter, B. F. (2013). The gender citation gap in international relations. International Organization,67(4), 889–922.

Martin, B. R. (1996). The use of multiple indicators in the assessment of basic research. Scientometrics,36(3), 343–362.

Martín-Martín, A., Orduna-Malea, E., Thelwall, M., & López-Cózar, E. D. (2018). Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. Journal of Informetrics,12(4), 1160–1177.

Maske, K. L., Durden, G. C., & Gaynor, P. (2003). Determinants of scholarly productivity among male and female economists. Economic Inquiry,41, 555–564.

Masuoka, N., Grofman, B., & Feld, S. L. (2007a). The political science 400: A twenty-year update. PS: Political Science and Politics,40(January), 133–145.

Masuoka, N., Grofman, B., & Feld, S. L. (2007b). Ranking departments: A comparison of alternative approaches. PS: Political Science and Politics,40(July), 531–537.

McCormick, J. M., & Rice, T. W. (2001). Graduate training and research productivity in the 1990s: A look at who publishes. PS: Political Science and Politics,34(September), 675–680.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1987). Validation of the Five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,52, 81–90.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A five factor theory perspective (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

McDermott, R., Dawes, C., Prom-Wormley, E., Eaves, L., & Hatemi, P. K. (2013). MAOA and aggression: A gene–environment interaction in two populations. Journal of Conflict Resolution,57(6), 1043–1064.

Mearsheimer, J. J., & Walt, S. M. (2013). Leaving theory behind: Why simplistic hypothesis testing is bad for International Relations. European Journal of International Relations,19(3), 427–457.

Mitchell, S. M., & Hesli, V. L. (2013). Women don’t ask? Women don’t say no? Bargaining and service in the political science profession. PS: Political Science and Politics,46(2), 355–369.

Oleynick, V. C., DeYoung, C. G., Hyde, E., Kaufman, S. B., Beaty, R. E., & Silva, P. J. (2017). Openness/intellect: The core of the creative personality. In G. J. Feist, R. Reiter-Palmon, & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity and personality research (pp. 9–27). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Payton, M. E., Greenstone, M. H., & Schenker, N. (2003). Overlapping confidence intervals or standard error intervals: What do they mean in terms of statistical significance? Journal of Insect Science,3, 34–39.

Roberts, B. W., & Mroczek, D. (2008). Personality trait change in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(January), 31–35.

Roettger, W. B. (1978). Strata and stability: Reputations of American political scientists. PS: Political Science and Politics,11(Winter), 6–12.

Rushton, J. P., Murray, H. G., & Paunonen, S. V. (1983). Personality, research creativity, and teaching effectiveness in university professors. Scientometrics,5(2), 93–116.

Sak, U., Ayvaz, U., Bal-Sezerel, B., & Ozdemir, N. N. (2017). Creativity in the domain of mathematics. In J. C. Kaufman, V. P. Glaveanu, & J. Baer (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity across domains (pp. 276–298). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Simonton, D. K. (1988). Scientific genius. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Simonton, D. K. (2009). Varieties of (scientific) creativity: A hierarchical model of domain-specific disposition, development, and achievement. Perspectives on Psychological Science,4(5), 441–452.

Simonton, D. K. (2014). Historiometric studies of genius. In D. K. Simonton (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of genius (pp. 87–106). Chichester: Wiley.

Somit, Albert, & Tanenhaus, Joseph. (1964). American political science. New York: Atherton.

Teele, D., & Thelen, K. (2017). Gender in the journals: Publication patterns in political science. PS: Political Science and Politics,50(2), 433–447.

Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wildavsky, A. (1989). Craftways. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Witte, K. D., & Rogge, N. (2010). To publish or not to publish? On the aggregation and drivers of research performance. Scientometrics,85, 657–680.

Funding

No grants funded this research, we have no apparent conflicts of interest, the data are not yet available (but can be in the interests of replication—contact the authors).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors are listed in alphabetical order.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and Figs. 4, 5.

Source: PASS Data for Political Science, 2017. Note: The figure shows 76% confidence intervals. Comparison of two 76% confidence intervals is equivalent to a 90% (p = .10, two-tailed) test of statistical significance at the point of overlap

The interactive effects of conscientiousness and openness are consistent across ranks.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Djupe, P.A., Hill, K.Q., Smith, A.E. et al. Putting personality in context: determinants of research productivity and impact in political science. Scientometrics 124, 2279–2300 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03592-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03592-5