Abstract

A vagueness-based approach to the mass/count distinction was developed in Chierchia (2010). Liebesman (2015) argues against Chierchia’s proposal developing four arguments against it. He furthermore tries to make a case that regardless of the details of C’s proposal no vagueness-based account of the distinction is viable. In this paper I show that Liebesman’s arguments against C don’t go through and that a line of investigation on the mass count contrast in terms of vagueness is not only viable but also perhaps a source of insight on the nature of this much debated distinction and on the relations between grammar and metaphysics in general. The outcome of the present discussion is of interest beyond the question of who is right in this debate, as it puts into sharper focus several issues pertaining to mass vs. count, plural vs. singular, and the role of vagueness in natural language semantics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Strictly speaking, C adheres to the classical bidimensional Kaplanian view according to which worlds play distinct roles when they fix the value of indexicals vs. when they are used to model propositional content. So, the arguments that follow should be couched in terms of ‘natural characters’ rather than ‘natural properties/contents’. However, the Kaplanian distinction between character and content is particularly relevant to issues, such as the interpretation of demonstratives within attitude reports or conditionals, which are largely orthogonal to the present concerns. It is therefore appropriate (and arguably safe) to follow the ways of classical Montague semantics (e.g. Montague 1970) and bypass such distinction within the present discussion, as it will greatly simplify our exposition. Cf. fn. 2 for a way of translating the present proposal into a Kaplanian bi-dimensional framework.

Here is a more explicit way of restating the semantics of the English word ‘cat’, in a more or less standard Kaplanian mold. For any context c, world w and individual u, the English word /kæt/ denotes a function cat, such that \(\mathbf{cat}(\hbox {c})(\hbox {w})(\hbox {u}) = 1\) if u is a cat in w according to the conventions prevailing among the English speaking community in c; \(\mathbf{cat}(\hbox {c})(\hbox {w})(\hbox {u})=0\) if u is not a cat according to the conventions prevailing among the English speaking community in c; and cat(c)(w)(u) is undefined otherwise. The English sentence that is a cat is true relative to a context c iff whatever that refers to in c (say u) is a cat relatively to the world of the context \(\hbox {w}_{\mathrm{c}}\) (i.e. iff \(\mathbf{cat}(\hbox {c})(\hbox {w}_{\mathrm{c}})(\hbox {u})=1\)). The formula \(cat_{w}(x)\) in the text can be taken as an abbreviation for \(\mathbf{cat}(\hbox {c})(\hbox {w}_{\mathrm{c}})(\hbox {x})\), and all of the examples in this paper can straightforwardly be restated along similar lines.

For the notions of ‘world of the context’ and ‘conventions prevailing in a community of speakers’ cf., e.g., Chierchia and McConnell-Ginet (2000, Chaps. 4, 6.2) and references therein.

\(\hbox {a}\le _{\mathrm{w}}\hbox {b}=_{\mathrm{df}}\hbox {a}\cup _{\mathrm{w}}\hbox {b}=\hbox {b}\). See Link (1983) for a classic formulation. The present discussion could be readily re-couched, with no modifications of substance, within set-theoretic approaches to plurality, such as, e.g., Schwarzschild (1996). For general introductions to the issues discussed here, cf., e.g., Pelletier and Schubert (1989) or Krifka (1994).

The plural property \(\uplambda \hbox {w}.\hbox {CAT}_{\mathrm{w}}\) includes singularities in its positive extension to ensure that that sentences like there are no cats on the mat comes out false if there is even a single cat on the mat. The intuition that there are cats on the mat is either false or infelicitous if there is just one cat on the mat is generally attributed to a scalar implicature triggered by the existence of an alternative (there is a cat on the mat) better suited to the context at hand. Cf. e.g. Sauerland (2003), Spector (2007), Mayr (2015) for discussion and implementations.

w is \(\propto \hbox {-minimal}=_{\mathrm{df}}\forall \hbox {w}'[\,\hbox {w}'\propto \hbox {w}\rightarrow \hbox {w}' =\hbox {w}]\).

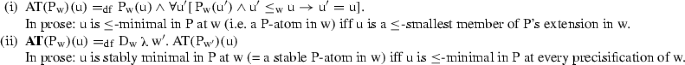

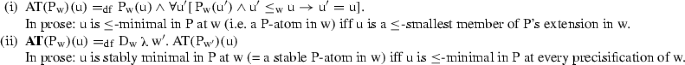

Here are the relevant definitions. For any natural property P,

For any natural property P, we only count stable P-atoms (i.e. objects in P whose atomicity (‘one-ness’) we are reasonably sure of on the basis of the prevailing conventions.

An interpretation of D more in line with an epistemicist stance should also be possible if ‘\(\propto \)’ is reinterpreted as ordering epistemic states.

Definition (7b) has as a consequence that ‘that \(\hbox {H}_{2}\hbox {O}\) molecule is water’ must be false or undefined for any ground context. I think this is plausible: the term ‘that \(\hbox {H}_{2}\hbox {O}\) molecule’ is hardly part of English, and its intended referent (a particular molecule) would have none of the properties native speakers impute to water samples in a naturalistic setting.

One might wonder: So what if C’s proposal is incompatible with a particular version of supervaluationism? The real question is whether C’s proposal is right! However, C clearly engages supervaluationism and views his proposal as a development of that line of thinking, and so discussing how C’s proposal might fit with a supervaluationist take on the problem of the many can be enlightening. L also claims that C’s approach is incompatible with a second popular approach to the problem of the many, namely Lewis’s (1993) ‘counting solution’. However, figuring out whether C’s take is also compatible with Lewis’s, while interesting in its own right, appears to be totally orthogonal to C’s stated goals.

The actual rendering of ‘there is exactly one cloud’ would be

-

(i)

\(\exists \hbox {x}[\mathbf{AT}(\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{w}})(\hbox {x}) \wedge \forall \hbox {y}[\mathbf{AT}(\hbox {P}_{\mathrm{w}})(\hbox {y})\rightarrow \hbox {y}=\hbox {x}]\)

Formula (i) entails (9i) in the text in virtue of the definition of AT (cf. fn. 6).

-

(i)

The ‘not strict enough’ part of the allegation refers to the fact that C does not discuss sentences like “I own one and a half cars”. But it is completely orthogonal to the mass count issue how to add fractions to a system of integers. If one relies on a notion of atom or singularity, one can clearly avail oneself of the notion of one half, one third, etc. of an atom/singularity.

The example in the text is very close to one discussed in C (cf. p. 122) and in what follows I paraphrase and try to elucidate C’s proposal, with the crucial help of one of the anonymous referees (who is of course not responsible for my way of interpreting his/her suggestions).

I.e. the truth of the following formula is not warranted in the context under discussion:

-

(a)

\(!\hbox {D}_{\mathrm{w}1}\uplambda \hbox {w}.\exists \hbox {x}[3(\mathbf{AT}(\hbox {mountains}_{\mathrm{w}}))(\hbox {x})\wedge \hbox {snow-covered}_{\mathrm{w}}(\hbox {x})]\)

where \(\hbox {w}_{1}\) is the actual context.

-

(a)

As one anonymous referee points out, if one has no clue as to what beeches are, one cannot know what it is to be one beech (or two, or n beeches); if I know that beeches are trees I can at best analogize with what it is to be one tree.

Following much work in syntax, I say that the constituent pieces of chocolate (which is part of the larger constituent those pieces of chocolate) is a Noun Phrase (NP), while those pieces of chocolate or every piece of chocolate is a Determiner Phrase (as it includes the determiners that and every).

See, e.g., C Sect. 5.2 for one way of analyzing these structures.

For one way of spelling out the notion of ‘natural logic’, cf., e.g., Chierchia (2013, Chap. 1) and references therein.

Of course, as is well known, mass-nouns generally admit count uses on the ‘type’ reading:

-

(a)

I like only two wines: Chianti and Prosecco.

Also count nouns have ‘type’ readings:

-

(b)

Two whales are seriously endangered: sperm whales and humpback whales.

-

(a)

Cf., e.g., Barner and Snedeker (2005) for some differences between mass nouns like furniture and canonical ones like water in English. See C, Sect. 6.1, for an account of nouns like furniture.

References

Barner, D., & Snedeker, J. (2005). Quantity judgments and individuation: Evidence that mass nouns count. Cognition, 97, 41–66.

Carey, S. (1985). Conceptual change in childhood. Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books, MIT Press.

Carey, S., & Spelke, E. (1996). Science and core knowledge. Philosophy of Science, 63(4), 515–533.

Chierchia, G. (2010). Mass nouns, vagueness, and semantic variation. Synthese, 174, 99–149.

Chierchia, G. (2013). Logic in grammar. London: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, G. (2015). How universal is the mass/count distinction? Three grammars of counting. In Y. A. Li, A. Simpson, & W. D. Tsai (Eds.), Chinese syntax in a cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, G., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2000). Meaning and grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Darlymple, M., & Morfu, S. (2012). Plural semantics, reduplication, and numeral modification in Indonesian. Journal of Semantics, 29(2), 229–260.

Holm, J. (2000). An introduction to pidgins and creoles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Worlds, words and contexts. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Krifka, M. (1994). Mass expressions. In R. E. Asher & J. M. Y. Simpson (Eds.), The encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Lewis, D. (1993). Many, but almost one. In J. Bacon, K. Campbell, & L. Reinhardt (Eds.), Ontology, causality, and mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Liebesman, D. (2015). Does vagueness underlie the mass/count distinction?. Synthese, Springer, Online version, doi:10.1007/s11229-015-0752-y.

Lima, S. (2014). The grammar of individuation and counting. Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Link, G. (1983). The logical analysis of plurals and mass terms. A lattice-theoretic approach. In R. Bauerle, C. Schwartz, & A. von Stechow (Eds.), Meaning, use and interpretation of language. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Mayr, C. (2015). Plural definite NPs presuppose multiplicity via embedded exhaustification. manuscript, ZAS, Berlin. Forthcoming in the Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 14.

Montague, R. (1970). Universal Grammar. In Theoria, 36. (pp. 373–398). Reprinted in R. Thomason (ed) Formal Philosophy, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1974.

Pelletier, J., & Schubert, F. (1989). Mass expressions. In D. Gabbay & F. Guenthner (Eds.), Handobook of philosophical logic (Vol. IV). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Sauerland, U. (2003). A new semantics for number. In Proceedings of SALT 13. Ithaca, N.Y.: CLC Publications, Cornell University.

Schwarzschild, R. (1996). Pluralities. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Spector, B. (2007). Aspects of the pragmatics of plural morphology: On higher order implicatures. In U. Sauerland & P. Stateva (Eds.), Presuppositions and implicatures in compositional semantics. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Weatherson, B. (2015). The problem of the many. In Edward N. Zalta (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2015 Edition). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2015/entries/problem-of-many/.

Acknowledgments

Versions of this paper were presented at ZAS (Berlin) in June 2015 and at a seminar at Harvard in the fall of 2015, co-taught with Roberta Pires de Oliveira and Roger Schwarzschild. I am grateful to those audiences for their feedback. I am also very grateful to three anonymous referees for their thorough comments and criticisms that have led me to revise many key points in the original argumentation. All remaining errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chierchia, G. Clouds and blood. More on vagueness and the mass/count distinction. Synthese 194, 2523–2538 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1063-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1063-7