Abstract

Context

The study of platinum (Pt) clusters and nanoparticles is essential due to their extensive range of potential technological applications, particularly in catalysis. The electronic properties that yield optimal catalytic performance at the nanoscale are significantly influenced by the size and structure of Pt clusters. This research aimed to identify the lowest-energy conformers for Pt\(_{18}\), Pt\(_{19}\), and Pt\(_{20}\) species using Density Functional Theory (DFT). We discovered new low-symmetry conformers for Pt\(_{19}\) and Pt\(_{20}\), which are 3.0 and 1.0 kcal/mol more stable, respectively, than previously reported structures. Our study highlights the importance of using density functional approximations that incorporate moderate levels of exact Hartree-Fock exchange, alongside basis sets of at least quadruple-zeta quality. The resulting structures are asymmetric with varying active sites, as evidenced by sigma hole analysis on the electrostatic potential surface. This suggests a potential correlation between electronic structure and catalytic properties, warranting further investigation.

Methods

An equivariant graph neural network interatomic potential (NequIP) within the Atomic Simulation Environment suite (ASE) was used to provide initial geometries of the aggregates under study. DFT calculations were performed with the ORCA 5 package, using functional approximations that included Generalized Gradient Approximation (PBE), meta-GGA (TPSS, M06-L), hybrid (PBE0, PBEh), meta-GGA hybrid (TPSSh), and range-separated hybrid (\(\omega \)B97x) functionals. Def2-TZVP and Def2-QZVP as well as members of the cc-pwCVXZ-PP family to check basis set convergence were used. QTAIM calculations were performed using the AIMAll suite. Structures were visualized with the AVOGADRO code.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Platinum nanoparticles are highly versatile species that find application in a wide range of fields due to their electrochemical [1, 2] and optical properties [3, 4]. Their importance is even more pronounced in the field of catalysis [5, 6] and especially for the photocatalytic production of H\(_2\) [7,8,9,10]. Indeed, the importance of hydrogen gas production can hardly be overemphasized, being central to various industrial sectors, including oil refining and steel processing. Furthermore, achieving a global increase in the production of H\(_2\) is essential for the decarbonisation of heavy industry, long-haul transportation, and seasonal energy storage [11]. In this context, the catalytic activity of small Pt clusters outperforms that of larger nanoparticles and bulkier metals due to their unique structures and electronic properties [12, 13]. Understanding the reasons behind these outstanding characteristics could potentially lead to the development of cheaper and more abundant catalysts, thereby advancing sustainable hydrogen production and helping to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels in the fight against climate change [14].

This background has given rise to a wide interest in acquiring a comprehensive understanding of the electronic properties and structure of small Pt nanoparticles, whose catalytic performance is strongly influenced by their shape and size [15]. Consequently, significant effort has been invested in identifying the most thermodynamically stable structures of different small platinum clusters. Despite the high computational cost associated with Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations in comparison to other methodologies such as the Gupta [16] or Sutton-Chen [17] model potentials, they have been the preferred approach for this endeavor. For instance, Kumar and Kawazoe [18], on one hand, and Wei and Liu [19], on the other, conducted systematic investigations using the PBE functional and projected augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials to identify isomers of up to 44 and 46 atoms, respectively. These studies have indicated that the addition of single atoms to existing clusters may prove an effective method for identifying novel minimum structures [20]. The search for the most stable structures of these moieties has employed a wide range of techniques, including biased searches [21], prescreening using empirical potentials [22], genetic algorithms [22, 23], simulated annealing [24], or a combination of them. Moreover, specific studies have focused on finding the global minimum (GM) of specific individual clusters, such as Pt\(_{13}\) [21, 25,26,27,28], Pt\(_{15}\) [22, 24], and Pt\(_{55}\) [26, 29, 30]. The use of different functionals or methodologies may result in varying conformer orderings, and this has occasionally given rise to controversies. This underscores the necessity for highly reliable results, which can be achieved by considering a number factors, including the use of large and flexible enough basis sets [31] or of appropriate aproximate exchange-correlation functionals that incorporate a suitable amount of Hartree-Fock exchange [32].

With this in mind, we employed a simulated annealing procedure based on molecular dynamics simulations, using a machine learning potential trained from DFT calculations, to investigate the structures of Pt\(_{18}\)–Pt\(_{20}\). This approach led to the discovery of new and asymmetric stable minima for Pt\(_{19}\) and Pt\(_{20}\). While the structure of the new minimum for Pt\(_{19}\) is similar to the previously reported ones, the new minimum for Pt\(_{20}\) differs significantly from previously accounted structures. Furthermore, our analysis incorporates different DFT approaches and emphasizes the importance of incorporating moderate amounts of Hartree-Fock exchange and the use of large basis sets to accurately determine the energetic ordering of platinum clusters. Finally, employing the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM), we have reveiled the differences in the electronic distribution of the two lowest isomers of the Pt\(_{20}\) cluster. We believe that the insights presented in this article will (i) provide important guidelines for the design of future simulations of these systems and (ii) contribute to the accurate energetic ordering of isomers leading to the identification of bona fide GM of metallic clusters.

Results and discussion

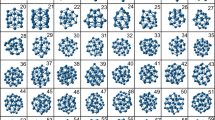

Figure 1 depicts the structures of the lowest-lying energy isomers of Pt\(_{18}\), Pt\(_{19}\), and Pt\(_{20}\). The xyz files corresponding to each structure at the TPSSh level of theory are available as Supporting Information. For Pt\(_{18}\), we confirm that the GM, 18.1, is the three-layer trigonal prism structure with D\(_{3{\textrm{h}}}\) symmetry proposed by Kumar and Kawazoe [18]. Furthermore, an analogous structure, slightly higher in energy, was identified wherein a Pt atom is displaced in an upward direction from the base, creating a rectangular opening in one of the sides of the pyramid. This results in C\(_s\) symmetry. The third Pt\(_{18}\) isomer depicted in Fig. 1 exhibits a distorted three-layer trigonal prism structure with C\(_2\) symmetry. It is noteworthy that this isomer is identified as the GM when described with the M06-L and \(\omega \)B97x functionals. As will be discussed in greater detail below, meta-GGA functionals tend to disfavor the three-layer trigonal prism structure. Despite repeated attemps, it was not possible to optimize the 18.1 isomer using the \(\omega \)B97x functional.

It is notable that the use of functional approximations that partially incorporate exact Hartree-Fock exchange results in a reduction in the energy differences between the 18.1 and 18.2 isomers. Indeed, the aforementioned discrepancy is 4.4 kcal/mol for the TPSS functional, while it is only 0.4 kcal/mol for the TPSSh, which includes 10% HF exchange. Furthermore, going from the PBE to the PBE0 functional reverses the energetic order of the isomers. With PBE, 18.1 is the lowest energy isomer, while 18.2 is the GM for PBE0, a hybrid functional with 25% exact HF exchange. Indeed, it is established that the inclusion of HF exchange can be pivotal in ensuring the correct energetic ordering [33]. This is because it mitigates the many-electron self-interaction error. This error arises from the inability of approximate exchange-correlation functionals to exclude the interaction of an electron with itself. Consequently, the inclusion of exact exchange facilitates a more precise characterization of electronic systems [34, 35].

In the case of Pt\(_{19}\), a novel GM, designated as the 19.1 structure, was identified that exhibits subtle differences from the previously reported minima, 19.2. Both structures are derived from the addition of a Pt atom to one of the triangular sides of the Pt\(_{18}\) three-layer trigonal prism (18.1). In the case of 19.2, the atom is added to one of the interstitial spaces between three other Pt atoms, resulting in a structure with C\(_s\) symmetry. With regard to the 19.1 isomer, the additional atom is located at an equal distance from the three sides of the triangular face of the three-layer trigonal prism, thereby resulting in C\(_{3v}\) symmetry. The third reported isomer, 19.3, exhibits no symmetry elements beyond the identity element. Regarding the energetic order, in this case, there is a more uniform assessment from the different functionals: PBE, PBE0, TPSS, and TPSSh all favor the 19.1 structure as the GM. In contrast, and similarly to what happens with Pt\(_{18}\), the M06-L and \(\omega \)B97x functionals predict disordered structures over those containing a three-layer trigonal prism, with a difference in energy of over 10 kcal/mol. As was the case with 18.1, it was not possible to optimize 19.1 using the \(\omega \)B97x functional.

For Pt\(_{20}\), the minimum energy structure proposed in previous works [18, 19, 22] (20.2) is a three-layer trigonal prism with two platinum atoms appended to one of its sides. In contrast, our proposed GM (20.1) possesses C\(_{1}\) symmetry and can be better described as a square base formed by nine Pt atoms, with a second and third levels formed by six and five Pt atoms, respectively. It appears that this unstructured arrangement favors the number of connecting atoms over the directionality of connections, which may indicate the initial stages of the transition from ordered nanoclusters to a metallic arrangement. The third isomer of Pt\(_{20}\) put forward in Fig. 1, 20.3, is formed by a rhomboidal-like base with nine atoms with two additional levels on top containing seven and four atoms, respectively. At first glance, its symmetry appears to be C\(_2\)-like; however, the presence of minor discrepancies between the edges destroys this pseudo-symmetry, leaving 20.3 as an additional C\(_1\) isomer. Energetically, the TPSS, TPSSh, and \(\omega \)B97x functionals render 20.1 as the GM. The PBE0 functional yields quasi-degenerate energies for the 20.1 and 20.2 isomers, and PBE favors the latter by 3.1 kcal/mol. Ultimately, optimization of the 20.2 isomer was not feasible when using the M06-L functional. Regarding the energetic ordering of the other two isomers, 20.3 sits 5.4 kcal/mol lower in energy. Notice, however, that the M06-L 20.3 structure has C\(_2\) symmetry (Table 1).

On the role of the basis set

Besides the importance of selecting the correct functional approximation, the selection of basis sets is of paramount importance for the accurate assignment of the energy ordering in these systems. Figure 2 illustrates the relative energy of the 20.1 cluster as compared to 20.2 for different basis sets taken from the cc-pwCVXZ-PP family [36]. We observe that the smallest basis set, cc-pwCVDZ-PP with 1080 functions, places 20.1 higher in energy than 20.2. However, when the cc-pwCVTZ-PP basis set is considered, 20.1 is correctly identified as the true GM. Notably, this behavior is not oscillatory, and the selection of 20.1 as the GM is confirmed by the larger cc-pwCVQZ-PP and cc-pwCV5Z-PP basis sets, which have 2880 and 4120 functions, respectively. These results suggest that the use of basis sets of at least QZ quality is essential for the accurate differentiation of conformers with similar energies.

Table 2 illustrates the relative energies of the 20.1 and 20.2 isomers using different functionals and basis sets of triple and quadruple-zeta quality. In particular, we selected the functionals mentioned above (PBE, PBE0, TPSS, TPSSh, and \(\omega \)B97x) and included also the popular BP86 [37, 38] and B3PW91 [39, 40] approximations in combination with the Def2-TZVP (TZ) and Def2-QZVPP (QZ) basis sets. Remarkably, older GGA functionals (BP86 and PBE) exhibited a pronounced preference for 20.2 over 20.1, with energy differences of 9.8 and 7.9 kcal/mol, respectively. Moreover, the incorporation of exact exchange has a clear stabilizing effect on 20.1 relative to 20.2: while PBE/TZ favored 20.2 by 7.9 kcal/mol, PBE0/TZ favored it only by 5.2 kcal/mol, a difference of 2.7 kcal/mol. In contrast, the newer \(\omega \)B97x, a range-separated hybrid functional, favored the 20.1 isomer by 4.2 kcal/mol.

It is striking that the transition from TZ to QZ-quality basis sets has significant implications for all functionals, irrespective of whether they are GGA, meta-GGA, or hybrid. Using the PBE functional and the TZ basis sets, 20.2 is 7.9 kcal/mol more stable than 20.1, while using the QZ basis reduces this difference to only 3.1 kcal/mol. Even more importantly, the use of QZ basis sets is cabable of reversing the energetic ordering, as observed with the TPSS and TPSSh functionals. For TPSS/TZ, 20.2 is the GM, while it is 20.1 in the case of TPSS/QZ. Indeed, going from the TZ to the QZ basis sets favors 20.1 over 20.2 by approximately 5 kcal/mol, regardless of its reference value. This is observed in the last column of Table 2. From these observations, we can infer that basis sets incompleteness has a selective impact on the relative stability of different isomers. Furthermore, these findings confirm the importance of using high-quality basis sets to obtain meaningful results for relative energies and other properties [31]. Our results emphasize the importance of selecting an appropriate functional approximation and a sufficiently large basis set to ascertain the relative stability of metal clusters in general and \(\text {Pt}_{\textrm{n}}\) isomers in particular.

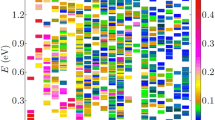

Electrostatic potential (\(V_{\textrm{S}}\)) mapped onto the van der Waals envelope for the minimum energy structures of Pt\(_{18}\), Pt\(_{19}\), and Pt\(_{20}\). \(\sigma \)-holes, identified as maximally negative \(V_{\textrm{S}}\) sites, are highlighted by yellow arrows. See the text for further details

IR fingerprints

In order to provide fingerprints for structural identification, we have calculated the vibrational modes of the most stable clusters. The characteristic peaks for Pt\(_n\) (n=18, 19, 20) clusters were found at 194.3, 207.6, and 200.8 cm\(^{-1}\), respectively. These correspond to the antisymmetric stretching of the central layers. The lowest vibrational frequencies, observed at 27.1, 25.7, and 16.8 cm\(^{-1}\), are twisting vibrations, while the vibrations at the highest frequencies are located at 214.0, 213.7, and 225.6 cm\(^{-1}\), are antisymmetric. The IR spectra of these clusters were generated using the orca_mapspc utility within the ORCA program and are shown in Fig. 3. These spectra could serve as benchmarks for future experimental characterization of Pt clusters.

Electrostatic potentials and QTAIM analyses

Theoretical studies on the lowest energy structures of Pt clusters provide insight into the underlying mechanisms that contribute to their excellent catalytic performance, as observed in experiments [24]. The overall catalytic efficiency of a given aggregate can be related to the existence of specific catalytically active sites, which are determined by the location of low-coordinated atoms within the cluster structure. As observed in gold and other noble metals, such sites lead to electron-deficient regions, the so-called \(\sigma \)-holes, that can be evaluated via the electrostatic potential mapped onto the van der Waals envelope (conveniently approximated as an electron density isosurface with isovalue 0.001 a.u.) [41, 42].

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the resulting electrostatic potential surface indicates the formation of six equivalent low-coordinated edges in Pt\(_{18}\), which give rise to six analogous \(\sigma \)-holes. These pinpoint reactive sites, as evidenced by the negative values of the electrostatic potential (\(V_{\textrm{S}}\)). The addition of a Pt atom to form Pt\(_{19}\) results in three equivalent \(\sigma \)-holes that retain some characteristics of the Pt\(_{18}\) parent, together with the appearance of a new deep hole around the capping atom. We thus expect different reactive sites in different regions of the cluster. This is exacerbated in Pt\(_{20}\), where the marked decrease in symmetry gives rise to several different \(\sigma \)-hole sites. Since the number of catalytic active regions in this cluster is greater than that observed in Pt\(_{18}\) and Pt\(_{19}\), we conclude that this cluster will be particularly reactive. Hence, the controlled growth of these types of aggregates may prove an effective strategy for modifying the number of catalytic sites within a narrow size range.

The Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) is a powerful tool for studying chemical interactions within a molecule. It allows for an orbital invariant analysis of electron density, thereby providing insights into the nature and strength of interactions between atoms. The QTAIM has been successfully employed in the study of intermetallic interactions [43,44,45] and metallic clusters [46,47,48,49,50,51]. Figure 5 provides such an analysis for the 20.1 and 20.2 clusters, illustrating both the bond paths [52, 53] between the platinum atoms and their atomic charges [54]. The electron densities of these two clusters are strikingly similar, exhibiting concentration of charge at the edge atoms coupled with a depletion of density in the interior atoms, which have a larger number of immediate neighbors. This is in contrast with previous findings in Al\(_{\textrm{n}}\)Sc clusters, where the electron density was found to be larger for the endohedral atom [51]. Furthermore, Fig. 5 also shows a two-dimensional relief map of the Laplacian of the electron density. This dissection reveals charge depletion zones that coincide with the catalytic active areas depicted in Fig. 4. This observation suggests a potential link between the distribution of the electron density near the nucleus and the catalytic properties of these Pt clusters, which merits further investigation.

Methods

We employed a machine-learning interatomic potential constructed from DFT energies and forces calculated at the TPSS/Def2-TZVP level of theory in order to ease the mapping of the complex potential energy surface of the Pt\(_{20}\) clusters. This potential was developed using E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks within the NequIP program by Batzner and coworkers [55], and it was used in conjunction with the Atomic Simulation Environment suite [56]. We used this interatomic potential to perform simulated annealing minimisations based on molecular dynamics simulations. The resulting structures were reoptimised using different exchange-correlation functionals, namely BP86 [37, 38], PBE [57], PBEh [58], PBE0 [59], B3PW91 [39, 40], TPSS [60], TPSSh [61], M06-L [62], and \(\omega \)B97x [63], in combination with the Def2-TZVP (TZ) and Def2-QZVP (QZ) [64,65,66] basis sets which include a relativistic pseudopotential replacing 60 core electrons of the platinum atom. With the aim of calibrating the performance of DFT methods, in our previous work, we conducted a benchmark calculation for Pt\(_2\) dimers described by different types of functionals [23]. By comparing the ionization potential and dissociation energies of these clusters, the results indicated that the hybrid-GGA M06-L, B3PW91, and meta-GGA TPSS functionals were good choices to evaluate the structures of the clusters. Interestingly, the TPSSh functional provided a bond length of 2.34 Å, which is slightly smaller than that predicted by TPSS (with 2.35 Å), but in better agreement with the experiment of Airola and Morse [67] (2.33 Å). Thus, the TPSSh functional seems realiable in predicting molecular geometries and vibrational frequencies for these systems. All DFT calculations were conducted with the aid of the Orca 5 software [68]. For the QTAIM [54] analyses, densities were obtained using the Zeroth-Order Regular Approximation [69,70,71], and the density partitions themselves were carried out using the AIMAll program [72]. The resulting structures were visualized using the Avogadro code [73].

Conclusion

In this study, we employed Density Functional Theory (DFT) to investigate the lowest energy structures and electronic properties of Pt\(_{18}\), Pt\(_{19}\), and Pt\(_{20}\) clusters. Our findings have revealed the existence of novel, more stable isomers for the Pt\(_{19}\) and Pt\(_{20}\) systems, 3.0 and 1.0 kcal/mol more stable, respectively, than the previously reported minimum energy structures. Furthermore, the role of different DFT approximations, including GGA (PBE), meta-GGA (TPSS, M06-L), hybrid (PBE0), meta-GGA hybrid (TPSSh), and range-separated hybrid (\(\omega \)B97x) functionals, was investigated in relation to the relative energies of the studied clusters. Our findings indicate that the energy ordering of different isomers is highly sensitive to the use of density functional approximations that include some exact Hartree-Fock exchange. Furthermore, it is evident that the use of basis sets of at least quadruple-zeta quality is necessary. A QTAIM analysis highlights significant distinctions in both the electron distribution and the nature of interatomic contacts among isomers, even those with comparable total energies. The MEP of the novel Pt\(_{20}\) minimum indicates the existence of potential catalytic sites. The insights presented in this article are expected to facilitate the design of future simulations and contribute to the accurate energetic ordering of isomers of metallic clusters, ultimately enabling the identification of true global minima in noble metal clusters as prototypical catalytic reactive species.

Supplementary information

A supplementary file with the structures of the studied clusters is available.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Hrapovic S, Liu Y, Male KB et al (2003) Electrochemical biosensing platforms using platinum nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Anal Chem 76(4):1083–1088. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac035143t

Claussen JC, Kumar A, Jaroch DB et al (2012) Nanostructuring platinum nanoparticles on multilayered graphene petal nanosheets for electrochemical biosensing. Adv Funct Mater 22(16):3399–3405. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201200551

Zhang N, Han C, Xu YJ et al (2016) Near-field dielectric scattering promotes optical absorption by platinum nanoparticles. Nat Photonics 10(7):473–482. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2016.76

Samadi A, Bendix PM, Oddershede LB (2017) Optical manipulation of individual strongly absorbing platinum nanoparticles. Nanoscale 9(46):18449–18455. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nr07374g

Cheng N, Banis MN, Liu J et al (2014) Extremely stable platinum nanoparticles encapsulated in a zirconia nanocage by area-selective atomic layer deposition for the oxygen reduction reaction. Adv Mater 27(2):277–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201404314

Choi KM, Na K, Somorjai GA et al (2015) Chemical environment control and enhanced catalytic performance of platinum nanoparticles embedded in nanocrystalline metal–organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc 137(24):7810–7816. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b03540

Cheng N, Stambula S, Wang D et al (2016) Platinum single-atom and cluster catalysis of the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat Commun 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13638

Zhang J, Zhao Y, Guo X et al (2018) Single platinum atoms immobilized on an MXene as an efficient catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat Catal 1(12):985–992. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-018-0195-1

Mei L, Gao X, Gao Z et al (2021) Size-selective synthesis of platinum nanoparticles on transition-metal dichalcogenides for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem Commun 57(23):2879–2882. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cc08091h

Tang P, Lee HJ, Hurlbutt K et al (2022) Elucidating the formation and structural evolution of platinum single-site catalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Catal 12(5):3173–3180. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c05958

Griffiths S, Sovacool BK, Kim J et al (2021) Industrial decarbonization via hydrogen: a critical and systematic review of developments, socio-technical systems and policy options. Energy Res Soc Sci 80:102208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102208

Imaoka T, Kitazawa H, Chun WJ et al (2013) Magic number Pt13 and misshapen Pt12 clusters: which one is the better catalyst? J Am Chem Soc 135(35):13089–13095. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja405922m

Schweinberger FF, Berr MJ, Döblinger M et al (2013) Cluster size effects in the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. J Am Chem Soc 135(36):13262–13265. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja406070q

Acar C, Dincer I (2019) Review and evaluation of hydrogen production options for better environment. J Clean Prod 218:835–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.046

Ahmadi TS, Wang ZL, Green TC et al (1996) Shape-controlled synthesis of colloidal platinum nanoparticles. Sci 272(5270):1924–1925. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.272.5270.1924

Gupta RP (1981) Lattice relaxation at a metal surface. Phys Rev B 23(12):6265–6270. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.23.6265

Sutton AP, Chen J (1990) Long-range Finnis–Sinclair potentials. Philos Mag Lett 61(3):139–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500839008206493

Kumar V, Kawazoe Y (2008) Evolution of atomic and electronic structure of Pt clusters: planar, layered, pyramidal, cage, cubic, and octahedral growth. Phys Rev B 77(20). https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.77.205418

Wei GF, Liu ZP (2016) Subnano Pt particles from a first-principles stochastic surface walking global search. J Chem Theory Comput 12(9):4698–4706. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00556

Rodríguez-Kessler PL, Rodríguez-Domínguez AR, Muñoz-Castro A (2021) Systematic cluster growth: a structure search method for transition metal clusters. Phys Chem Chem Phys 23(8):4935–4943. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cp06179d

Rodríguez-Kessler PL, Rodríguez-Domínguez AR (2015) Size and structure effects of PtN (N = 12 - 13) clusters for the oxygen reduction reaction: first-principles calculations. J Chem Phys 143(18). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4935566

Wang X, Tian D (2009) Structures and structural evolution of PtN (N=15–24) clusters with combined density functional and genetic algorithm methods. Comput Mater Sci 46(1):239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2009.02.031

Guevara-Vela JM, Rocha-Rinza T, Rodríguez-Kessler PL et al (2023) On the structure and electronic properties of PtN clusters: new most stable structures for N = 16–17. Phys Chem Chem Phys 25(42):28835–28840. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cp04455f

Rodríguez-Kessler PL, Muñoz-Castro A, Rodríguez-Domínguez AR et al (2023) Structure effects of Pt15 clusters for the oxygen reduction reaction: first-principles calculations. Phys Chem Chem Phys 25(6):4764–4772. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cp05188e

Watari N, Ohnishi S (1998) Atomic and electronic structures of Pd13 and Pt13 clusters. Phys Rev B 58(3):1665–1677. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.58.1665

Aprá E, Fortunelli A (2003) Density functional calculations on platinum nanoclusters: Pt13, Pt38, and Pt55. J Phys Chem A 107(16):2934–2942. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0275793

Chang CM, Chou MY (2004) Alternative low-symmetry structure for 13-atom metal clusters. Phys Rev Lett 93(13). https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.93.133401

Piotrowski MJ, Piquini P, Da Silva JLF (2010) Density functional theory investigation of 3\(d\), 4\(d\), an 5\(d\) 13-atom metal clusters. Phys Rev B 81(15). https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.81.155446

Da Silva JLF, Kim HG, Piotrowski MJ, et al (2010) Reconstruction of core and surface nanoparticles: the example of Pt55 and Au55. Phys Rev B 82(20). https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.82.205424

Ewing CS, Veser G, McCarthy JJ et al (2015) Effect of support preparation and nanoparticle size on catalyst–support interactions between Pt and amorphous silica. J Phys Chem C 119(34):19934–19940. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b05763

Neese F (2009) Prediction of molecular properties and molecular spectroscopy with density functional theory: from fundamental theory to exchange-coupling. Coord Chem Rev 253(5–6):526–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.014

Tekarli SM, Drummond ML, Williams TG et al (2009) Performance of density functional theory for 3d transition metal-containing complexes: utilization of the correlation consistent basis sets. J Phys Chem A 113(30):8607–8614. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp811503v

Hostaš J, Pérez-Becerra KO, Calaminici P et al (2023) How important is the amount of exact exchange for spin-state energy ordering in DFT? Case study of molybdenum carbide cluster, Mo4C2. J Chem Phys 159(18). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0169409

Mori-Sánchez P, Cohen AJ, Yang W (2006) Many-electron self-interaction error in approximate density functionals. J Chem Phys 125(20). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2403848

Cohen AJ, Mori-Sánchez P, Yang W (2011) Challenges for density functional theory. Chem Rev 112(1):289–320. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr200107z

Figgen D, Peterson KA, Dolg M et al (2009) Energy-consistent pseudopotentials and correlation consistent basis sets for the 5d elements Hf–Pt. J Chem Phys 130(16). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3119665

Perdew JP (1986) Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys Rev B 33(12):8822–8824. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.33.8822

Becke AD (1988) Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys Rev A 38(6):3098–3100. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.38.3098

Perdew JP, Chevary JA, Vosko SH et al (1992) Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys Rev B 46(11):6671–6687. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.46.6671

Becke AD (1993) Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys 98(7):5648–5652. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.464913

Stenlid JH, Brinck T (2017) Extending the \(\sigma \)-hole concept to metals: an electrostatic interpretation of the effects of nanostructure in gold and platinum catalysis. J Am Chem Soc 139(32):11012–11015. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b05987

Stenlid J, Johansson A, Brinck T (2017) \(\sigma \)-holes on transition metal nanoclusters and their influence on the local Lewis acidity. Curr Comput-Aided Drug Des 7(7):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst7070222

Puyo M, Lebon E, Vendier L et al (2020) Topological analysis of Ag–Ag and Ag–N interactions in silver amidinate precursor complexes of silver nanoparticles. Inorg Chem 59(7):4328–4339. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b03166

Guevara-Vela JM, Hess K, Rocha-Rinza T et al (2022) Stronger-together: the cooperativity of aurophilic interactions. Chem Commun 58(9):1398–1401. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1cc05241a

Burguera S, Bauzá A, Frontera A (2024) A novel approach for estimating the strength of argentophilic and aurophilic interactions using QTAIM parameters. Phys Chem Chem Phys 26(23):16550–16560. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4cp00410h

Mandado M, Krishtal A, Alsenoy CV et al (2007) Bonding study in all-metal clusters containing Al4 units. J Phys Chem A 111(46):11885–11893. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp074973y

Foroutan-Nejad C (2012) Al\(_4^{2-}\); the anion-\(\pi \) interactions and aromaticity in the presence of counter ions. Phys Chem Chem Phys 14(27):9738. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cp40511c

Badri Z, Pathak S, Fliegl H et al (2013) All-metal aromaticity: revisiting the ring current model among transition metal clusters. J Chem Theory Comput 9(11):4789–4796. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct4007184

Foroutan-Nejad C (2021) Bonding and aromaticity in electron-rich boron and aluminum clusters. J Phys Chem A 125(6):1367–1373. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.0c11474

Lacaze-Dufaure C, Bulteau Y, Tarrat N et al (2022) Coordination of ethylamine on small silver clusters: structural and topological (ELF, QTAIM) analyses. Inorg Chem 61(19):7274–7285. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c03870

Guevara-Vela JM, de la Vega AS, Gallegos M et al (2023) Wave function analyses of scandium-doped aluminium clusters, AlnSc (n= 1–24), and their CO\(_2\) fixation abilities. Phys Chem Chem Phys 25(28):18854–18865. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cp01730c

Bader RFW (1998) A bond path: a universal indicator of bonded interactions. J Phys Chem A 102(37):7314–7323. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp981794v

Martín Pendás Á, Francisco E, Blanco M et al (2007) Bond paths as privileged exchange channels. Chem Eur J 13(33):9362–9371. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200700408

Bader RFW (1990) Atoms in molecules: a quantum theory. Oxford University Press

Batzner S, Musaelian A, Sun L et al (2022) E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat Commun 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29939-5

Hjorth Larsen A, Jørgen Mortensen J, Blomqvist J et al (2017) The atomic simulation environment—a python library for working with atoms. J Phys: Condens Matter 29(27):273002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648x/aa680e

Perdew JP, Burke K, Wang Y (1996) Generalized gradient approximation for the exchange-correlation hole of a many-electron system. Phys Rev B 54(23):16533–16539. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.54.16533

Heyd J, Scuseria GE, Ernzerhof M (2003) Hybrid functionals based on a screened coulomb potential. J Chem Phys 118(18):8207–8215. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1564060

Adamo C, Barone V (1999) Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: the PBE0 model. J Chem Phys 110(13):6158–6170. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.478522

Tao J, Perdew JP, Staroverov VN et al (2003) Climbing the density functional ladder: nonempirical meta–generalized gradient approximation designed for molecules and solids. Phys Rev Lett 91(14). https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.91.146401

Staroverov VN, Scuseria GE, Tao J et al (2003) Comparative assessment of a new nonempirical density functional: molecules and hydrogen-bonded complexes. J Chem Phys 119(23):12129–12137. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1626543

Zhao Y, Truhlar DG (2006) A new local density functional for main-group thermochemistry, transition metal bonding, thermochemical kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J Chem Phys 125(19). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2370993

Chai JD, Head-Gordon M (2008) Systematic optimization of long-range corrected hybrid density functionals. J Chem Phys 128(8). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2834918

Weigend F, Ahlrichs R (2005) Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys Chem Chem Phys 7(18):3297–3305. https://doi.org/10.1039/b508541a

Weigend F (2006) Accurate coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys Chem Chem Phys 8(9):1057. https://doi.org/10.1039/b515623h

Hellweg A, Hättig C, Höfener S et al (2007) Optimized accurate auxiliary basis sets for RI-MP2 and RI-CC2 calculations for the atoms Rb to Rn. Theor Chem Acc 117(4):587–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-007-0250-5

Airola MB, Morse MD (2002) Rotationally resolved spectroscopy of Pt2. J Chem Phys 116(4):1313–1317. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1428753

Neese F (2017) Software update: the ORCA program system, version 4.0. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci 8(1):e1327. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1327

van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG (1993) Relativistic regular two-component Hamiltonians. J Chem Phys 99(6):4597–4610. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.466059

van Leeuwen R, van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ et al (1994) Exact solutions of regular approximate relativistic wave equations for hydrogen-like atoms. J Chem Phys 101(2):1272–1281. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.467819

van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG (1994) Relativistic total energy using regular approximations. J Chem Phys 101(11):9783–9792. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.467943

Keith TA (2019) Aimall (version 19.02.13). TK Gristmill Software, Overland Park KS, USA, 2019 (aim.tkgristmill.com)

Hanwell MD, Curtis DE, Lonie DC et al (2012) Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J Cheminform 4(1):2946–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2946-4-17

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by FONDECYT ANID Regular 1221676. Powered@NLHPC: This research was partially supported by the supercomputing infrastructure of the NLHPC (ECM-02). IPICyT’s National Supercomputing Center supported this research with the computational time grant TKII-E-0424-I-080424-4/PR-6. T.R.-R. is thankful to DGTIC/UNAM for computer time (project LANCAD-UNAM-DGTIC 250). A.M.P. and M.G. thank MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF A way of Making Europe, grants PID2021-122763NB-I00. M.G. also thanks the Spanish MICIU for a predoctoral FPU grant, FPU19/02903.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.G.-V. and T.R.-R. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript text. M.G. and P.L.R-K. and A.M-C. performed the theoretical calculations. Á.M.-C., P.L.R.-K., and A.M.P. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guevara-Vela, J.M., Gallegos, M., Rocha-Rinza, T. et al. New global minimum conformers for the Pt\(_{19}\) and Pt\(_{20}\) clusters: low symmetric species featuring different active sites. J Mol Model 30, 310 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-024-06099-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-024-06099-5