Abstract

The integration of numerical simulations with Liver-on-a-Chip (LoC) technology offers an innovative approach for studying liver physiology and pathology, especially in the context of liver cancer. Numerical simulations facilitate the optimization of microfluidic devices’ design and deepen the understanding of fluid flow and mass transfer. However, despite significant advancements, challenges such as replicating the full complexity of the liver microenvironment and scaling up for high-throughput screening persist. This systematic review explores the current advancements in LoC devices, with a particular emphasis on their combined use of numerical simulations and experimental studies in liver cancer research. A comprehensive search across multiple databases, including ScienceDirect, Wiley Online Library, Scopus, Springer Link, Web of Science, and PubMed, was conducted to gather relevant literature. Our findings indicate that the combination of both techniques in this field is still rare, resulting in a final selection of 13 original research papers. This review underscores the importance of continued interdisciplinary research to refine these technologies and enhance their application in personalized medicine and cancer therapy. By consolidating existing studies, this review aims to highlight key advancements, identify current challenges, and propose future directions for this rapidly evolving field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer is a complex disease characterized by several hallmarks, including sustained proliferative signaling, evasion of growth suppressors, resistance to cell death, replicative immortality, induction of angiogenesis, and activation of invasion and metastasis (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011; Hanahan 2022). These hallmarks, first defined by Hanahan and Weinberg, provide a framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of cancer progression and its resistance to therapy (Hanahan and Weinberg 2000). Liver cancer exemplifies these characteristics and poses a significant global health burden, characterized by a high mortality rate that is expected to increase by 6.7% by 2025 (WHO 2024a, 2024b). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which constitutes up to 80% of liver cancer cases, is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, limiting treatment options (Rumgay et al. 2022a, 2022b; McGlynn et al. 2021). Despite advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, the prognosis for liver cancer remains poor, with a five-year survival rate of less than 20% for advanced-stage diagnoses (Yang and Roberts 2010; Calderon-Martinez et al. 2023). This highlights the critical need for innovative approaches in disease modeling and drug development.

Current treatments for liver cancer include surgical resection (Imamura et al. 2003), liver transplantation (Mazzaferro et al. 1996), radiofrequency ablation (Vakili et al. 2009), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) (Lo et al. 2002), radioembolization (Sangro et al. 2011), immunotherapy (Sangro et al. 2021), and systemic therapies (Kudo et al. 2018; Panagiotis and Chau 2024). While these treatments can be effective, they often come with significant limitations. Surgical options are only viable for a small subset of patients with early-stage disease, and liver transplantation is limited by donor availability and the risk of recurrence (Llovet et al. 2021). Furthermore, radiofrequency ablation and transarterial chemoembolization may not be suitable for advanced-stage tumors, and systemic therapies frequently result in severe side effects and may only extend survival by a few months (Forner et al. 2018; Rezaei 2023). These challenges emphasize the pressing need for more effective and less toxic treatment options for liver cancer.

In response to these limitations, researchers are exploring alternative treatments, including novel targeted therapies (Huang et al. 2020; Li et al. 2022a; Zhao et al. 2022; Seidi et al. 2022; Moukhtari et al. 2023), gene therapies (Hernández-alcoceba et al. 2007; Reghupaty and Sarkar 2019; Kohn et al. 2023), and combination treatments to improve outcomes for liver cancer patients (Liu et al. 2021; Taha et al. 2022; Gao et al. 2015). However, evaluating the efficacy and safety of these new approaches requires robust preclinical testing. This is where in vitro models become crucial (Hrout et al. 2022; Blidisel et al. 2021; Yao et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2015; Bonanini et al. 2022). Traditional in vitro and in vivo models, although valuable, exhibit limitations in accurately replicating the human microenvironment and predicting patient responses to therapy. Conventional 2D cell cultures, for instance, fail to reproduce the complex 3D architecture and physiological conditions of human organs, leading to poor translational outcomes (Godoy et al. 2013; Kapałczyńska et al. 2018). Similarly, animal models, while offering a systemic context that can be informative, often fail to accurately replicate the complexity of the disease, including tumor heterogeneity, immune interactions, and the dynamic nature of the organ’s microenvironment. Furthermore, their use raises significant ethical concerns (Kiani et al. 2022; Atat et al. 2022). To bridge the gap between conventional models and human physiology, advanced in vitro systems such as 3D spheroid cultures, organoids, and microfluidic-based Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) technology have emerged as promising platforms (Maia et al. 2022; Carvalho et al. 2021a; Prodanov et al. 2016). Spheroids and organoids offer enhanced cellular interactions and more accurate functional replication of human tissue compared to 2D cultures (Nguyen et al. 2021; Luo et al. 2024; Lee et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2023). However, while these systems offer advantages over traditional models, they still face challenges in fully replicating the complexity of the cancer’s microenvironment and its interactions with other organ systems (Harane et al. 2023; Arora et al. 2024). These models often operate under static conditions, whereas the human body exists in a dynamic environment with constant fluid flow, mechanical forces, and evolving cellular interactions. As a result, they may fall short in accurately modeling tumor behavior, and drug responses. Furthermore, spheroids and organoids often lack the full range of cell types and the native extracellular matrix (ECM) found in organs, which limits their physiological relevance. In contrast, organotypic cultures offer a more comprehensive cell population and native ECM structure, closely mimicking in vivo tissue architecture and function (de Hoyos-Vega et al. 2023; Hattersley et al. 2011, 2008). OoC technology has further advanced the field by integrating microfluidics and 3D culture models to more closely mimic the in vivo environment (Liu et al. 2022a; Carvalho et al. 2022; Sontheimer-Phelps et al. 2019; Driver and Mishra 2023). These devices typically consist of a network of microchannels and chambers that can include multiple cell types, extracellular matrix components, and fluid flow to closely mimic cellular heterogeneity and structural complexity. Additionally, a key advantage of microfluidic devices is their ability to facilitate the accumulation and controlled circulation of endogenous growth factors, which allows cells to better retain their phenotype over extended periods compared to conventional static cultures. This accumulation of growth factors, alongside dynamic fluid flow, enhances cellular function and viability, offering a more stable and physiologically relevant environment. Recent studies have explored how hepatic growth factors accumulate and are secreted within these devices, underscoring the value of microfluidics in sustaining cell-specific functions and advancing tissue modeling (Lu et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2015; Hoyos-Vega et al. 2024). Because of all these characteristics, OoC technology has rapidly evolved since its inception in 2010 (Huh et al. 2010). This pioneering work introduced a lung-on-a-chip device, which successfully replicated the critical functions of the human alveolar-capillary interface. Since then, the field has rapidly evolved, leading to the development of various organ-specific chips, including Liver-on-a-Chip (LoC) devices (Mirzababaei et al. 2023; Lee et al. 2019; Polidoro et al. 2024; Xie et al. 2022), which have been used for diverse purposes such as investigating the effects of substances on gene expression profiles (Solan et al. 2023), studying metabolomic interactions between liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatocytes (Tian et al. 2022; Messelmani et al. 2024, 2023), evaluating the genotoxicity and mutagenicity of drugs (Kopp et al. 2024), impact of proteins in liver cancer progression (Shen et al. 2023), study cardiotoxicity (Soltantabar et al. 2021), cell resistance (Poddar et al. 2024), drug toxicity (Kim et al. 2022; Lee et al. 2023), cell separation/isolation (Xue et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2017a, 2020, 2017b; Rodríguez-Pena et al. 2022), and detection purposes (Deepak et al. 2024).

The integration of computational simulations with OoC systems presents a powerful approach to accelerate research by offering predictive tools that complement experimental studies and help improve device performance for specific applications (Carvalho et al. 2021b). This typically involves creating a virtual representation of the microchannel network, and model interactions between diverse elements: flow rates, materials properties, cellular properties (e.g., molecular consumption), design factors, and other conditions such as temperature, pressure, oxygen levels, pH, and diffusion rates for various solutes, including nutrients and growth factors, among others (Choe et al. 2017; Jeon et al. 2020). Generally, the modeling process involves initial design, mesh generation, defining flow conditions, material properties, and boundary conditions, simulation, and whenever possible, validation against experimental data. By enabling precise control over critical parameters, such as flow dynamics and shear stress, computational modeling can serve as a powerful predictive tool for assessing the impact of design variations and experimental conditions (e.g., nutrient levels and availability). These predictive insights encompass the ability to anticipate system behavior, such as how specific design changes or parameter adjustments will affect device performance or replicate physiological conditions. In doing so, computational modeling minimizes reliance on extensive trial-and-error experimentation, accelerating the development process. While the initial investment in computational tools, such as hardware and software licenses, may be substantial, these tools deliver long-term cost savings by reducing the need for consumables, manual labor, and repeated physical prototyping. Although specific cost comparisons depend on the context, the scalability and reusability of computational tools typically result in cumulative cost efficiency over multiple tests (Carvalho et al. 2024; Solovchuk et al. 2013; Li et al. 2022b; Zhang et al. 2021). Moreover, computational modeling facilitates an in silico high-throughput approach to testing diverse design scenarios and parameter configurations. This allows researchers to rapidly evaluate multiple configurations in silico, systematically identifying promising designs or conditions for experimental assays. Finally, by integrating computational modeling with experimental data, researchers can iteratively refine and validate their models. This integration enhances predictive accuracy and reliability, ensuring that the insights generated align closely with experimental outcomes.

Fluid flow dynamics simulations are widely used in OoC systems’ research to enhance microfluidic channel geometries, flow rates, and shear stress parameters, enabling researchers to mimic the mechanical cues that cells experience in vivo more accurately (Saeedabadi et al. 2022; Jun-Shan et al. 2017). Similarly, modeling nutrient and oxygen gradients is crucial for recreating tissue-like microenvironments in OoC devices, as it helps ensure effective nutrient distribution across cell layers and improve the device to provide adequate levels for the experiments, creating a more physiologically relevant platform for cell culture (Wang et al. 2018). Additionally, computational models are helpful in simulating the transport, and efficacy of therapeutic agents within OoC systems. These predictive models enable researchers to assess drug distribution and diffusion kinetics within tissue analogs, refining both device parameters and experimental protocols (Barisam et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2022).

Common computational approaches in the OoC field include the Finite volume method (FVM), and finite element modeling (FEM). FVM divides the simulation domain into control volumes and applies conservation laws for mass, momentum, and energy directly over each volume (Versteeg and Malalasekera 2007), and is commonly implemented in software such as ANSYS Fluent. On the other hand, FEM breaks down the domain into elements and uses interpolation functions to approximate the solution, which is advantageous for complex geometries and varying material properties (Liu et al. 2018). FEM is often applied in OoC to model structural mechanics, such as tissue deformation due to its flexibility with complex boundaries. COMSOL Multiphysics is a popular FEM-based software in these applications.

This holistic perspective accelerates translational research by enabling the development of more effective preclinical models. However, significant challenges hinder their full potential, as outlined in Table 1.

Accurately modeling complex biological environments, such as the liver, is challenging due to its complex microarchitecture, diverse cell types, and spatially varying oxygen and nutrient levels. Simulating these elements alongside dynamic cellular signaling and metabolic reactions requires advanced models and substantial computational resources, potentially limiting their accessibility to many research labs.

Furthermore, validating computational models for OoC research becomes more costly and challenging when incorporating cellular components, as complex experiments are often difficult to fully replicate in silico, and model simplifications are required. For instance, simplifying material properties (both device and ECM), cellular behaviors, molecular diffusion coefficients, and assuming ideal conditions (e.g., Newtonian fluids, laminar flow, smooth channels) can compromise the physiological relevance of model predictions.

Moreover, generalizing computational results across studies remains challenging due to variations in methods, parameters, and biological contexts. Thus, findings from a specific model may not apply broadly due to restricted study conditions. Lack of standardization, however, refers to inconsistencies in methods, protocols, and parameters across studies, leading to discrepancies that make comparisons and interpretations difficult.

Addressing these challenges is crucial to maximizing the impact of computational models in advancing translational research.

Although the potential of integrating LoC technology with computational modeling is evident, a comprehensive evaluation of this combined approach in liver cancer research is still lacking. Furthermore, despite several reviews addressing LoC devices for various applications (Ortega-Ribera 2024; Xie et al. 2023; Aina 2023; Deng et al. 2019), they often overlook the integration of computational tools. This systematic review aims to bridge this gap by thoroughly assessing the current state of LoC devices designed to replicate HCC, the most common type of primary liver cancer, and evaluating their use in conjunction with computational modeling. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no previous systematic review has explored this integration in detail.

Methodology

Literature search

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across ScienceDirect, Wiley Online Library, Scopus, Springer Link, and PubMed using the following query ((("liver-on-a-chip" OR "liver chip" OR "microfluidic device") AND ("numerical simulation" OR "mathematical model" OR simulation) AND ("liver cancer" OR "hepatocellular carcinoma" OR "hepatocelular carcinoma"))). The search was conducted on 5th July 2024.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review were original research articles that combine numerical and experimental approaches in LoC devices for cancer research and full-text articles. The exclusion criteria included abstracts, non-English language articles, literature reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, book chapters, short communications, conference articles, patents, case reports, and books.

Data analysis

After selecting the articles from the databases, they were organized in an Excel sheet to remove duplicates. Two authors independently conducted the same selection process, and then compared and discussed their results until reaching a consensus. If uncertainties remained about the inclusion or exclusion of certain studies, a third author was consulted to provide input and assist in the final decision. Based on their reviews and analysis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a final selection of relevant studies was made.

Results and discussion

This section presents the PRISMA flowchart, outlining the paper selection process, followed by a detailed analysis and discussion of the selected studies and a table summarizing their key findings.

Study selection

In the ScienceDirect database, 58 research articles were identified. PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science each provided 2 results. The Wiley Online Library had 270 results, though many were review papers due to the inability to filter by paper type on the website. The search on SpringerLink returned 23 results, and 7 additional papers were identified from other sources. After removing duplicates, a total of 360 articles were reviewed. The initial selection was based on title screening, resulting in 61 articles that met the criteria for this systematic review. Next, abstracts of these 61 articles were evaluated, and 32 were selected for further review through full-text reading. Following a comprehensive screening of the full texts, 13 articles were selected for inclusion in the study. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process, and Fig. 2 displays the distribution of the published papers by year.

Integrating LoC technology with computational simulations

The integration of computational simulations and experimental approaches has significantly advanced the development of LoC models for cancer research. These sophisticated platforms can better replicate the complex liver microenvironment, facilitating precise drug testing and enhancing our understanding of liver physiology and disease mechanisms.

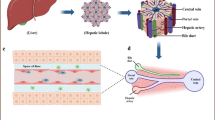

Some authors (Lim et al. 2021; Kang et al. 2020) have focused on replicating the tumor microenvironment, particularly under hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia is a common feature of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and plays a significant role in cancer progression. Under these conditions, cancer cells adapt and can contribute to tumor progression processes including tumor angiogenesis and proliferation, and become chemo-resistant. By replicating hypoxia in research models, researchers can better understand how tumors adapt and survive in low-oxygen environments, which is essential for developing more effective therapies. In light of this, Lim et al. (2021) developed a 3D in vitro tumor vasculature model for HCC in a hypoxia incubator (Fig. 3(a)).

Representation of the devices developed by the authors and their numerical outputs. (a) A 3D in vitro tumor vasculature model for HCC in a hypoxia incubator, and oxygen concentration after 1080 min. Reproduced with permission (Lim et al. 2021). Copyright 2021, Wiley. Open Access; (b) A microfluidic platform to generate continuous oxygen gradients and sulfite concentration distribution. Reproduced with permission (Kang et al. 2020, 2018). Copyright 2020, Wiley. Open Access, and Copyright 2018, Nature, Open Access; (c) Microfluidic device developed to create hypoxic conditions, and the oxygen concentration distribution over time obtained numerically. Reproduced with permission (Kim et al. 2023). Copyright 2023, Elsevier. OpenAccess, (d) Microfluidic device to establish an oxygen gradient, which directs the metabolic zonation, and the steady-state oxygen concentration obtained from the numerical simulations. Reproduced with permission (Tonon et al. 2019). Copyright 2019, Nature. OpenAccess

The results demonstrate that hypoxic stress in HCC vasculature promotes angiogenesis, HIF-1 expression, cell proliferation, and drug resistance, closely mimicking physiological tumor responses, making the microfluidic platform a promising tool for developing anticancer therapies targeting hypoxic tumor environments. Furthermore, the authors modeled the oxygen distribution within the platform to assess how external conditions influence the TME of HCC. The findings demonstrated that within 18 h, the external conditions fully compensated for the oxygen levels throughout the TME, providing a detailed spatial distribution of oxygen across the platform. In the same line of research, Kang et al. (2020) advanced the field by designing a microfluidic platform to generate continuous oxygen gradients, simulating both physiological and severe hypoxic conditions (0.3–6.9%), using a chemical oxygen‐quenching approach (Fig. 3(b)). The results confirmed that an ascending hypoxia gradient in hepatocytes led to decreased cell viability, increased reactive oxygen species accumulation, and higher HIF-1α expression, indicating distinct metabolic and genetic responses to varying oxygen levels. Herein, authors simulated sodium sulfite concentration gradients in the device, establishing well-separated compartments with varying concentrations by adjusting flow rates from 30 to 120 µL/h, and considering a diffusion coefficient of 1.2 × 10−9 m2/s in water, and a molecular weight of 126 Da. The authors experimentally validated their computational model in a previous study (Kang et al. 2018). In this case, they also tested different flow rates, but later fixed one flow rate, and evaluated the effect of different diffusion coefficients representing different species (3-MC, glucagon, and insulin) in the concentration profile. For validation purposes, they conducted laboratory experiments to test the impact of volumetric flow rate and molecular weight of inducers on the gradient profile. Initially, they visualized gradient formation in their microfluidic device using food colorings. Subsequently, they replicated their computer simulations, using three fluorescently labeled particles with varying molecular weights, and evaluated how the gradient profile matched the simulation predictions. The experimental results showed good agreement with the computational studies, although some imaging artifacts were noted. On the other hand, since albumin is a key biomarker of liver function, Kim et al. (2023) developed a hepatic hypoxia-on-a-chip with an electrochemical albumin sensor to investigate liver function changes under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3(c)). This contains an oxygen-scavenging channel with a gas-permeable membrane in between, to quickly induce hypoxia (below 5% within 10 min). Results showed a significant decrease in albumin secretion (27% reduction) under hypoxic conditions after 24 h compared to normoxia, aligning with in vivo studies. This system provides a promising approach for real-time monitoring of liver function in response to hypoxia. Computational simulations were conducted to evaluate the system's ability to induce hypoxia over time. A no-slip boundary condition was applied at the channel boundary (except for the polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane). The cell culture medium was modeled as air-saturated water, using an incompressible laminar flow at 100 µL/h, with a density of 1 g/cm3 and viscosity of 1 cP. In the oxygen-scavenging channel, water with 0% oxygen concentration flowed at 100 µL/min. Furthermore, a free and porous media flow model was applied for oxygen transport across the PDMS membrane, with a porosity of 1.0 × 10−6 and a permeability of 620 Barrer. The authors specifically assessed how the position of the oxygen scavenging channels influenced oxygen concentration in different regions of the cell culture channel, using numerical simulations to compare the two design variations.

From a different perspective, Tonon and co-workers (2019) introduced a novel approach by designing a microfluidic device composed of culture chambers and gas channels. This allows to establish an oxygen gradient, which directs the metabolic zonation (spatial variation in metabolic functions and gene expression across different regions of the liver) of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into differentiated hepatocytes, thereby replicating in vivo conditions (Fig. 3(d)). The results showed that the microfluidic device successfully generated an oxygen gradient that guided the differentiation of hESCs into hepatocytes, with high oxygen levels enhancing glycogen storage and specific gene expression related to liver function. Conversely, low oxygen conditions increased the expression of genes associated with metabolic activities and cell proliferation, indicating that the device can effectively simulate metabolic zonation and improve the understanding of hepatocyte physiology in varying oxygen environments. The authors numerically simulated the oxygen concentration over time within the microfluidic chip under conditions similar to standard normoxic biological incubators and accounting for cell oxygen consumption. The computational model was designed to simulate the steady-state effect of gas concentration in channels, using diffusion with flux, insulation, and concentration boundary conditions. The portion simulated consists of a culture chamber and gas chambers, designed to operate in a normoxic environment. Due to PDMS’s high gas permeability, stable oxygen levels were generated by diffusion across a membrane that separates gas and flow chambers. Additionally, the impact of insulating the top of the chip on concentration gradients was examined. At higher gas flow rates (> 0.1 mL/min), the oxygen concentration was stable across the channel length, equaling the inlet concentration. Oxygen diffusion coefficients used were: PDMS (4 × 10–9 m2/s), phosphate-buffered saline (2 × 10–9 m2/s), and air (2 × 10–5 m2/s). Experimentally, they used a ruthenium solution as a fluorescence sensor for oxygen concentration. The experimental oxygen profile matched the predictions from the computational model, confirming the simulation's accuracy and demonstrating that the chip could effectively create and maintain different oxygen zones within the culture chamber. By accurately mimicking the physiological conditions within the liver, such models can provide deeper insights into how cells interact with their environment, adapt to different metabolic zones, and respond to therapies.

Other studies have integrated multi-organ interactions to explore drug metabolism and potential side effects. Kamei et al. (2017) developed an integrated Heart/Cancer-on-a-Chip to study the cardiotoxic effects of doxorubicin (Dox), an anti-cancer drug. The device enables the modeling of cardiotoxicity caused by Dox, where toxic metabolites produced by HepG2 cells (liver cancer cell line) can affect heart cells through the circulatory system. The device comprised a perfusion layer with two cell culture chambers and microchannels for nutrient and drug supply and a control layer with pneumatic valves and peristaltic micro-pumps for independent cell culture and precise medium flow control. Computational simulations were used to simulate the hydraulic performance of PDMS membrane to determine its threshold hydraulic pressure. The simulation results, showing a threshold pressure of 65 kPa, were compared with experimental measurements of valve efficiency and flow rate, demonstrating that the simulated and measured threshold pressures were in close agreement (less than 3% difference). Additionally, fluorescent imaging confirmed that the pneumatic valve was fully closed at this threshold pressure of 65 kPa. On the other hand, Sharifi and co-workers (2020) developed a metastasis-on-a-chip platform designed to model and track the spread of HCC to bone tissue (Fig. 4(a)). The platform consists of two main chambers, one containing encapsulated liver cancer cells and another simulating a bone environment. A microporous membrane mimicking the vascular barrier is placed above these chambers. The authors observed that liver cancer cells proliferated within the tumor microenvironment and eventually migrated through the circulatory system into the bone chamber. To investigate potential treatments, the researchers tested an herb-based compound, in both free form and encapsulated in nanoparticles and the results showed that the nanomaterial provided a more sustained inhibitory effect on cancer cell migration compared to the free form. Overall, the HCC-bone metastasis-on-a-chip platform successfully modeled key aspects of cancer metastasis, demonstrating its potential for studying metastasis-related biology and screening anti-metastatic drugs. In addition to the experimental observations, the study incorporated numerical simulations to model fluid dynamics and oxygen transport within the bioreactor. The culture medium was modeled as a steady, incompressible, isothermal, Newtonian fluid. To determine the velocity distribution in the chamber and hydrogel matrix, the continuity, Navier–Stokes, and Brinkman equations were applied. Furthermore, with a Reynolds number (Re) of approximately 1, the flow was assumed to be laminar, allowing inertial terms to be disregarded. Cellular oxygen consumption was also included, and although PDMS is gas-permeable, all wall boundaries were treated as impermeable since the bioreactor was enclosed by two gas-impermeable poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) layers. The results revealed a laminar flow regime with a parabolic velocity profile at a perfusion rate of 5 µL/min, ensuring sufficient oxygen delivery to the HCC cells and preventing hypoxic conditions within the device.

Devices and numerical outputs obtained by the authors. (a) HCC–bone metastasis assembled bioreactor, computed velocity streamlines within the device, and oxygen concentration distribution. Reproduced with permission (Sharifi et al. 2020). Copyright 2020, Springer, (b) Liver-lobule-mimicking labchip, and simulations of electric-field distribution, and GelMA concentration gradient. Reproduced with permission (Chen et al. 2021). Copyright 2021, Elsevier, (c) A biomimetic LoC with vascularized liver tissue, Tri-Vascular Liver-on-a-Chip. The numerical outputs show the oxygen and glucose concentration distribution. Reproduced with permission (Liu et al. 2022b). Copyright 2022, Frontiers. OpenAccess, (d) 3D vascularized HCC-on-a-chip model, and simulated shear stress. Reproduced with permission (Özkan et al. 2023). Copyright 2023, Wiley. OpenAccess

The replication of the liver structure and function has also been explored by some researchers. Chen et al. (2021) created a microfluidic device to mimic the liver lobule structure and tested different GelMA concentrations (5%, 10%, and 15%) (Fig. 4(b)). Computational simulations were used to demonstrate how a strong electric field traps cells guiding cells into precise configurations between electrode layers to mimic liver lobule structures. The results showed that cells co-cultured in 5% GelMA exhibited the highest urea secretion and maintained a liver-lobule-like pattern, demonstrating that this microenvironment effectively preserves liver function and cell pattern despite variations in growth rates and medium flow. On the other hand, Liu et al. (2022b) developed a biomimetic LoC with vascularized liver tissue, a Tri-Vascular Liver-on-a-Chip (TVLOC), which includes a hepatic artery, a portal vein, and a central vein (Fig. 4(c)). Furthermore, the authors developed a bilayer microsphere-generating microsystem with distinct cell types. These bilayer microspheres were then co-cultured with endothelial cells within the TVLOC to form vascularized liver tissue. The results demonstrated that the TVLOC effectively mimics the liver microenvironment's substance concentration gradients and the bilayer microspheres successfully created a structured 3D liver tissue with endothelial cells. Computational tools were used to optimize the microwell size and flow rate and understand oxygen and glucose gradients over time. To this end, they simulated the hepatic artery and portal vein using two inlets, and one outlet representing the central vein. To analyze the nutrient concentration gradients resulting from the convergence of these flows, they developed a model in COMSOL software, and made several assumptions, namely that cell metabolites have a negligible impact on flow velocity, flow behavior is Newtonian, the properties of the medium match those of water at 37 °C, and the impact of cells on ECM porosity is negligible. At the inlet of the hepatic artery, the oxygen partial pressure was set to 90 mmHg and the glucose concentration to 1.0 g/L. At the inlet of the portal vein, the oxygen partial pressure was set to 30 mmHg with a glucose concentration of 4.5 g/L. The diffusion coefficients used were 2.92 × 10–9 m2/s for oxygen and 9 × 10–10 m2/s for glucose. For the boundary conditions, a uniform velocity at the inlets was considered (corresponding to 200 µL/h), while at the outlet, the pressure was set to 0 Pa, with a zero-flux concentration condition. Their model successfully maintained hepatocyte function and mimicked the liver microenvironment, demonstrating the utility of combining experimental and computational approaches. Özkan et al. (2023) introduced a 3D vascularized HCC-on-a-chip model to study the therapeutic efficacy of Dox under cirrhotic and inflamed cancer stages (Fig. 4(d)). The model effectively replicated the liver sinusoid's structure by employing concentric layers of cells and a collagen matrix. Findings indicated that increasing inflammation and vascular permeability, due to elevated inflammatory cytokines, led to variability in treatment outcomes. Specifically, enhancing CYP3A4 activity and using TACE to deliver Dox improved therapeutic responses and reduced the increase in endothelial porosity caused by chemotherapy. The model effectively showed how TME factors influence vascular properties, treatment efficacy, and drug delivery strategies. In this study, computational simulations were used to investigate shear stress (SS). They conducted flow simulations using COMSOL Multiphysics software, applying Stokes' Law to quantify flow within the vasculature. They assumed that the fluid had constant viscosity, was incompressible, and that Re was low, allowing them to neglect inertial terms. The simulations were run considering a constant flow rate of 59 μL/min at the inlet and a zero-gauge pressure at the outlet, with a vessel diameter of 435 µm. Additionally, they modeled flow in the ECM using Darcy’s Law, assuming isotropic tissue mechanical properties, considering a collagen porosity of 0.49 and a hydraulic permeability of 10 × 10–15 m2. The resulting flow profile was then used to calculate the SS at the vessel walls, with the endothelial layer thickness set equal to 15 µm and the thickness of the space equal to 138 µm. Oxygen consumption by the cells was also considered in their simulations. The authors verified that the aligned vascular endothelium was achieved by flowing culture medium at a SS of 1 dyn/cm2 over 3 days, replicating the conditions of the human liver tumor microenvironment.

Wu and co-workers (2022) developed a “digital OoC” system that integrates a microwell array with cellular microspheres to enhance parallel processing capabilities compared to traditional single-chamber OoC models, and 2D culture in 24-well plates. The microspheres prepared through electrospray ensure precise control over size and shape, addressing issues related to variability and contamination in drug testing. This new system can accommodate up to 127 uniform liver cancer microspheres as separate analytical units, allowing for consistent and rapid analysis. Note that both digital and traditional OoC models tested were maintained with medium perfusion at a flow rate of 0.25 mL/min. The digital platform demonstrated effective anti-cancer activity for sorafenib and showed better alignment with in vivo results compared to the other tested models. Herein, computational simulations were used to study the diffusion of drugs like sorafenib and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in 2% sodium alginate and compared the diffusion rates in two types of OoC systems, a traditional “single pot” model and a "digital OoC". For the numerical simulation, they used the diffusion coefficients of sorafenib (6.4 × 10–10 m2/s) and IFN-γ (1.0 × 10–10 m2/s) in 2% sodium alginate. The initial concentrations of sorafenib and IFN-γ were set at 10 μmol/L and 50 μg/mL, respectively. They employed the convection–diffusion equation to quantitatively analyze the diffusion rates of both small molecules (sorafenib, MW < 104) and large molecules (IFN-γ) in both types of devices. MATLAB software was utilized to solve the convection–diffusion equation. The results revealed that sorafenib, reached a steady-state concentration in the "digital OoC" within 17.3 s, whereas it took 215.9 s to achieve the same concentration in the traditional “single pot” OoC. For larger molecules like IFN-γ, diffusion reached equilibrium in 94.7 s in the "digital OoC", compared to 1594.3 s in the traditional model. This indicates that the "digital OoC" allows for significantly faster diffusion and equilibrium of both small and large molecules compared to the traditional setup. Bhise et al. (2016) developed a LoC supporting the long-term culture of 3D printed hepatic spheroids in GelMA and in situ monitoring. Over 30 days, the constructs maintained their functionality, as shown by liver-specific protein secretion and hepatocyte marker staining. The platform effectively mimicked acetaminophen toxicity observed in animal and in vitro models, demonstrating its potential for accurate drug toxicity assessment. Computational tools were employed to study oxygen concentration and different flow rates within a cell culture chamber, considering the porosity of hydrogel constructs. In this study, a no-slip boundary condition was applied at the walls, and the convection–diffusion equation was solved to model fluid flow and oxygen transport within the channels and chamber. Although PDMS is oxygen-permeable, all boundaries were treated as impermeable surfaces due to the PMMA layer covering the bioreactor. The hydrogels were modeled as porous media with a uniform volumetric oxygen consumption rate characterized by Michaelis–Menten kinetics, based on the total number of encapsulated cells. A constant and uniform oxygen concentration was specified at the inlet. The diffusion coefficient of oxygen in aqueous media at 37 °C was assumed to be approximately 3.8 × 10–9 m2/s. Furthermore, an unstructured 3D mesh was used and tested for grid independence, with results showing that a grid size of 800,000 nodes was sufficient to ensure independence from mesh size. Simulations showed that at a 200 µL/h flow rate, the minimum oxygen concentration dropped from 91% of the inlet value on day 1 to an average of 38% (with a minimum of 19%) on day 30. Flow rates higher than 200 µL/h maintained adequate oxygen levels for hepatocytes, thus a flow rate of 200 μL/h was used in subsequent experiments. A different study was presented by Docci et al. (2022). The researchers developed and explored a LoC system, PhysioMimix, to improve the in vitro study of drug metabolism and reduce reliance on animal testing. They assessed the system's ability to simulate liver functions by testing how well it mimics the metabolism of various drugs and how effectively it predicts drug behavior in the human body. Mathematical modeling was used to evaluate two different models, a linear model and an evaporation model, to estimate the intrinsic clearance (CLint), the rate at which the liver can metabolize a drug when it has unrestricted access to it, from observed in vitro data, considering experimental factors like evaporation, cell number, and sampling volume. Besides that, they utilized both models for a preliminary in silico simulation assessment to evaluate the adequacy of the two analyses. The evaporation model was specifically applied to generate in vitro concentration-time profiles across a range of theoretical in vitro CLint values, along with different evaporation rates. Regarding the numerical simulations, a constant number of cells (N) was considered and incorporated random effects for N and evaporation rate (coefficient of variation equal to 20% for both cases), reflecting their experience with experimental variability. A sampling volume of 18 μL was considered, and to assess variability, they simulated 1,000 concentration-time profiles using the evaporation model based on the previously described conditions. From this full dataset, they randomly sampled three replicates at various time points up to 96 h, repeating this random sampling 100 times. They estimated CLint values by fitting the data with either the linear model or the evaporation model. They then calculated the accuracy of the estimated mean CLint values using the root-mean-square error and assessed bias with the absolute average fold error. Additionally, they evaluated the median uncertainty from 100 experiments and determined the percentage relative standard error. A percentage greater than 30% was considered the threshold for CLint uncertainty. The integration of mathematical modeling with experimental data enhanced the estimation of drug metabolism and provided insights into the performance of the LoC system, demonstrating its potential for generating high-quality and relevant data for drug development.

Table 2 provides an overview of the studies previously discussed, highlighting the culture models developed, cell types used, study aims, the purpose of computational simulations, the software utilized, and whether the authors validated their computational models.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The integration of numerical simulations with experimental approaches has significantly advanced the development of LoC models, particularly in the context of cancer research. These sophisticated models effectively replicate the complex microenvironment of the liver, facilitating precise drug testing and deepening our understanding of liver physiology and disease mechanisms.

The 13 studies analyzed in this systematic review highlight the effectiveness of LoC models in replicating liver structure, function, and the tumor microenvironment. By recreating key factors such as hypoxic conditions, vascular interactions, and metabolic zonation, these models provide valuable insights into tumor progression and treatment responses. They also offer a platform for monitoring liver function under varying conditions. Curiously, although reviewed papers use dynamic conditions and microfluidic technology, most studies still seed cells in two dimensions, highlighting the potential for further innovation in future research. The successful integration of computational simulations has further enabled researchers to enhance device design, predict drug diffusion and concentration gradients, replicate complex liver structures such as the liver lobule, and improve flow conditions. However, the reviewed research articles also revealed certain limitations. Many authors did not mention conducting a mesh study, a critical step in ensuring the accuracy of numerical simulations. This involves refining the mesh and observing the convergence of results. This process ensures that the obtained solutions are independent of the mesh discretization and are accurate representations of the physical phenomena. Similarly, a sensitivity analysis should be conducted to evaluate the impact of varying boundary conditions and material properties on the simulation outcomes. By systematically investigating these factors, the reliability and robustness of computational models can be enhanced. Besides this, only three studies among those reviewed mentioned the comparison between the numerical and experimental outcomes to validate the computational model, which underscores a critical gap in ensuring the reliability and applicability of simulation results. Validation is crucial for confirming that the computational outputs are viable and can be extrapolated to experimental practice. For validating the computational model, experimental approaches could include both cell-free and cell-inclusive setups, each offering distinct insights. Validation without cells, such as fluid flow or mechanical deformation studies in empty OoC channels, enables the assessment of basic model parameters like flow dynamics and structural integrity under controlled conditions. While cellular experiments can provide more representative data for comparison with simulation results, it is essential to recognize that computational models can be firstly assessed for accuracy and potential in the absence of such data. Furthermore, one of the fully reviewed papers did not include any representation of computational results, merely presenting their conclusions without providing the supporting data or analysis. Additionally, while many studies claim device optimization, this is often an improvement rather than the result of the systematic application of optimization methods. Moreover, the computational studies presented typically focus on one or two outputs, with methodologies that are often too generalized and lacking in detail, limiting the ability to replicate these results. This highlights the need for more extensive validation and a deeper exploration of computational tools in future research on LoC devices. Despite these challenges, the combination of advanced experimental and computational techniques has led to the development of more physiologically relevant LoC models.

Future research should prioritize increasing the complexity of LoC models by incorporating additional cell types and organ systems. This would enable more comprehensive studies of multi-organ interactions and systemic drug effects, offering a holistic view of drug metabolism and toxicity. The development of patient-specific LoC models using cells derived from individual patients also holds great promise for personalized medicine, allowing therapies to be tailored to the specific genetic and environmental factors of a patient’s tumor. Moreover, refining computational models to better predict complex biological phenomena, such as cellular responses to dynamic microenvironments and drug interactions, will be crucial. This will likely involve the development of more sophisticated algorithms and the integration of machine learning techniques to handle the large datasets generated by these models. Advancements in scalability and automation will also be necessary to enable high-throughput screening, making these models more accessible and cost-effective for pharmaceutical research. Finally, the integration of advanced sensors and imaging techniques within LoC models will enable real-time monitoring of cellular responses and metabolic changes, providing more detailed insights into the dynamics of the liver microenvironment and improving the predictive power of these models.

Addressing these challenges will allow the field of LoC research to continue evolving, ultimately leading to more accurate and reliable models for studying liver cancer and other diseases, and thereby improving therapeutic outcomes.

It should be also noted that a limitation of this systematic review is the potential exclusion of studies where computational models and OoC experiments are not explicitly linked within a single publication. This is particularly relevant for well-established research groups or companies that employ the same OoC design across multiple applications. While internal integration of computational models and OoC experiments might exist, it may not be explicitly documented in a single paper, thus hindering their inclusion in this review.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Aina KO (2023) Isogenic hiPSC-derived liver-on-chip platforms: a valuable tool for modeling metabolic liver diseases. Asp Mol Med 2:100025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amolm.2023.100025

Arora S, Singh S, Mittal A, Desai N, Khatri DK, Gugulothu D, Lather V, Pandita D, Vora L (2024) Spheroids in cancer research: recent advances and opportunities. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 106033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2024.106033

Barisam M, Saidi MS, Kashaninejad N, Vadivelu R, Nguyen NT (2017) Numerical simulation of the behavior of toroidal and spheroidal multicellular aggregates in microfluidic devices with microwell and U-shaped barrier. Micromachines 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi8120358

Bhise NS, Manoharan V, Massa S, Tamayol A, Ghaderi M (2016) A liver-on-a-chip platform with bioprinted hepatic spheroids. Biofabrication 8:014101. https://doi.org/10.1088/1758-5090/8/1/014101

Blidisel A, Marcovici I, Coricovac D, Hut F, Dehelean C, Cretu O (2021) Experimental models of hepatocellular carcinoma — a preclinical perspective. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13153651

Bonanini F, Kurek D, Previdi S, Nicolas A, Hendriks D, de Ruiter S, Meyer M, Clapés Cabrer M, Dinkelberg R, García SB, Kramer B, Olivier T, Hu H, López-Iglesias C, Schavemaker F, Walinga E, Dutta D, Queiroz K, Domansky K, Ronden B, Joore J, Lanz HL, Peters PJ, Trietsch SJ, Clevers H, Vulto P (2022) In vitro grafting of hepatic spheroids and organoids on a microfluidic vascular bed. Angiogenesis 25:455–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-022-09842-9

Calderon-Martinez E, Landazuri-Navas S, Vilchez E, Cantu-Hernandez R, Mosquera-Moscoso J, Encalada S, Al Lami Z, Zevallos-Delgado C, Cinicola J (2023) Prognostic scores and survival rates by etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. J Clin Med Res 15:200–207. https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr4902

Carvalho V, Gonçalves IM, Lage T, Rodrigues RO, Minas G, Teixeira SFCF, Moita AS, Hori T, Kaji H, Lima RA (2021a) 3D printing techniques and their applications to organ-on-a-chip platforms : a systematic review. Sensors 21:3304. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21093304

Carvalho V, Rodrigues RO, Lima RA, Teixeira S (2021b) Computational simulations in advanced microfluidic devices: a review. Micromachines 12:1149. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi12101149

Carvalho V, Banobre M, Minas G, Teixeira S, Lima RA, Rodrigues RO (2022) The integration of spheroids and organoids into organ-on-a-chip platforms for tumour research : a review. Bioprinting 27:e00224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bprint.2022.e00224

Carvalho V, Gonçalves IM, Rodrigues N, Sousa P, Pinto V, Minas G, Kaji H, Shin SR, Rodrigues RO, Teixeira SFCF, Lima RA (2024) Numerical evaluation and experimental validation of fluid flow behavior within an organ-on-a-chip model. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2023.107883

Chen Y, Gao D, Liu H, Lin S, Jiang Y (2015) Drug cytotoxicity and signaling pathway analysis with three-dimensional tumor spheroids in a microwell-based microfluidic chip for drug screening. Anal Chim Acta 898:85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2015.10.006

Chen H, Cao B, Sun B, Cao Y, Yang K, Lin Y-S (2017a) Highly-sensitive capture of circulating tumor cells using micro-ellipse filters. Sci Rep 7:610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00232-6

Chen H, Cao B, Chen H, Lin Y-S, Zhang J (2017b) Combination of antibody-coated, physical-based microfluidic chip with wave-shaped arrays for isolating circulating tumor cells. Biomed Microdevices 19:66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10544-017-0202-3

Chen J, Liu C-Y, Wang X, Sweet E, Liu N, Gong X, Lin L (2020) 3D printed microfluidic devices for circulating tumor cells (CTCs) isolation. Biosens Bioelectron 150:111900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2019.111900

Chen YS, Tung CK, Dai TH, Wang X, Yeh CT, Fan SK, Liu CH (2021) Liver-lobule-mimicking patterning via dielectrophoresis and hydrogel photopolymerization. Sensors Actuators B Chem 343:130159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2021.130159

Choe A, Ha SK, Choi I, Choi N, Sung JH (2017) Microfluidic Gut-liver chip for reproducing the first pass metabolism. Biomed Microdevices 19:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10544-016-0143-2

de Hoyos-Vega JM, Gonzalez-Suarez AM, Cedillo-Alcantar DF, Stybayeva G, Matveyenko A, Malhi H, Garcia-Cordero JL, Revzin A (2024) Microfluidic 3D hepatic cultures integrated with a droplet-based bioanalysis unit. Biosens Bioelectron 248:115896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2023.115896

de Hoyos-Vega JM, Hong HJ, Loutherback K, Stybayeva G, Revzin A (2023) A microfluidic device for long-term maintenance of organotypic liver cultures. Adv Mater Technol 8. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202201121

Deepak KS, Balapure A, Priya PR, Kumar PS, Dubey SK, Javed A, Chattopadhyay S, Goel S (2024) Development of a microfluidic device for the dual detection and quantification of ammonia and urea from the blood serum. Sensors Actuators A Phys 369:115174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2024.115174

Deng J, Wei W, Chen Z, Lin B, Zhao W, Luo Y, Zhang X (2019) Engineered liver-on-a-chip platform to mimic liver functions and its biomedical applications: a review. Micromachines 10:1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi10100676

Docci L, Milani N, Ramp T, Romeo AA, Godoy P, Franyuti DO, Krähenbühl S, Gertz M, Galetin A, Parrott N, Fowler S (2022) Exploration and application of a liver-on-a-chip device in combination with modelling and simulation for quantitative drug metabolism studies. Lab Chip 22:1187–1205. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1lc01161h

Driver R, Mishra S (2023) Organ-on-a-chip technology: an in-depth review of recent advancements and future of whole body-on-chip. Biochip J 17:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13206-022-00087-8

El Atat O, Farzaneh Z, Pourhamzeh M, Taki F, Abi-Habib R, Vosough M, El-Sibai M (2022) 3D modeling in cancer studies. Hum Cell 35:23–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13577-021-00642-9

El Moukhtari SH, Garbayo E, Amundarain A, Pascual-Gil S, Carrasco-León A, Prosper F, Agirre X, Blanco-Prieto MJ (2023) Lipid nanoparticles for siRNA delivery in cancer treatment. J Control Release 361:130–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.07.054

El Harane S, Zidi B, El Harane N, Krause K-H, Matthes T, Preynat-Seauve O (2023) Cancer spheroids and organoids as novel tools for research and therapy: state of the art and challenges to guide precision medicine. Cells 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12071001

Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J (2018) Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 1301–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2

Gao J, Shi Z, Xia J, Inagaki Y, Tang W (2015) Sorafenib-based combined molecule targeting in treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 21:12059–12070. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12059

Godoy P, Hewitt NJ, Albrecht U, Andersen ME, Ansari N, Bhattacharya S, Bode JG, Bolleyn J, Borner C, Böttger J, Braeuning A, Budinsky RA, Burkhardt B, Cameron NR, Camussi G, Cho C-S, Choi Y-J, Craig Rowlands J, Dahmen U, Damm G, Dirsch O, Donato MT, Dong J, Dooley S, Drasdo D, Eakins R, Ferreira KS, Fonsato V, Fraczek J, Gebhardt R, Gibson A, Glanemann M, Goldring CEP, Gómez-Lechón MJ, Groothuis GMM, Gustavsson L, Guyot C, Hallifax D, Hammad S, Hayward A, Häussinger D, Hellerbrand C, Hewitt P, Hoehme S, Holzhütter H-G, Houston JB, Hrach J, Ito K, Jaeschke H, Keitel V, Kelm JM, Kevin Park B, Kordes C, Kullak-Ublick GA, LeCluyse EL, Lu P, Luebke-Wheeler J, Lutz A, Maltman DJ, Matz-Soja M, McMullen P, Merfort I, Messner S, Meyer C, Mwinyi J, Naisbitt DJ, Nussler AK, Olinga P, Pampaloni F, Pi J, Pluta L, Przyborski SA, Ramachandran A, Rogiers V, Rowe C, Schelcher C, Schmich K, Schwarz M, Singh B, Stelzer EHK, Stieger B, Stöber R, Sugiyama Y, Tetta C, Thasler WE, Vanhaecke T, Vinken M, Weiss TS, Widera A, Woods CG, Xu JJ, Yarborough KM, Hengstler JG (2013) Recent advances in 2D and 3D in vitro systems using primary hepatocytes, alternative hepatocyte sources and non-parenchymal liver cells and their use in investigating mechanisms of hepatotoxicity, cell signaling and ADME. Arch Toxicol 87:1315–1530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-013-1078-5

Hanahan D (2022) Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov 12:31–46. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2000) The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100:57–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144:646–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

Hattersley SM, Dyer CE, Greenman J, Haswell SJ (2008) Development of a microfluidic device for the maintenance and interrogation of viable tissue biopsies. Lab Chip 8:1842–1846. https://doi.org/10.1039/B809345H

Hattersley SM, Greenman J, Haswell SJ (2011) Study of ethanol induced toxicity in liver explants using microfluidic devices. Biomed Microdevices 13:1005–1014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10544-011-9570-2

Hernández-alcoceba R, Sangro B, Prieto J (2007) Gene therapy of liver cancer. Ann Hepatol 6:5–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31948-9

Hrout A, Gracia KC, Chahwan R, Amin A (2022) Modelling liver cancer microenvironment using a novel 3D culture system. Sci Rep 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11641-7

Huang A, Yang X, Chung W, Dennison AR, Zhou J (2020) Targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00264-x

Huh D, Matthews BD, Mammoto A, Montoya-Zavala M, Yuan Hsin H, Ingber DE (2010) Reconstituting organ-level lung functions on a chip. Science (80-.) 328:1662–1668. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188302

Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Tanaka E, Ohkubo T, Hasegawa K, Miyagawa S, Sugawara Y, Minagawa M, Takayama T, Kawasaki S, Makuuchi M (2003) Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J Hepatol 38:200–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00360-4

Jeon JW, Choi N, Lee SH, Sung JH (2020) Three-tissue microphysiological system for studying inflammatory responses in gut-liver Axis. Biomed Microdevices 22:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10544-020-00519-y

Jun-Shan L, Zhang YY, Wang Z, Deng JY, Ye X, Xue RY, Ge D, Xu Z (2017) Design and validation of a microfluidic chip with micropillar arrays for three-dimensional cell culture. Chin J Anal Chem 45:1109–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1872-2040(17)61029-6

Kamei KI, Kato Y, Hirai Y, Ito S, Satoh J, Oka A, Tsuchiya T, Chen Y, Tabata O (2017) Integrated heart/cancer on a chip to reproduce the side effects of anti-cancer drugs: in vitro. RSC Adv 7:36777–36786. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ra07716e

Kang YBA, Eo J, Mert S, Yarmush ML, Usta OB (2018) Metabolic patterning on a chip: towards in vitro liver zonation of primary rat and human hepatocytes. Sci Rep 8:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27179-6

Kang YB, Eo J, Bulutoglu B, Yarmush ML, Usta OB (2020) Progressive hypoxia-on-a-chip: an in vitro oxygen gradient model for capturing the effects of hypoxia on primary hepatocytes in health and disease. Biotechnol Bioeng 117:763–775. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.27225

Kapałczyńska M, Kolenda T, Przybyła W, Zajączkowska M, Teresiak A, Filas V, Ibbs M, Bliźniak R, Łuczewski Ł, Lamperska K (2018) 2D and 3D cell cultures - a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Arch Med Sci 14:910–919. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.63743

Kiani AK, Pheby D, Henehan G, Brown R, Sieving P, Sykora P, Marks R, Falsini B, Capodicasa N, Miertus S, Lorusso L, Dondossola D, Tartaglia GM, Ergoren MC, Dundar M, Michelini S, Malacarne D, Bonetti G, Dautaj A, Donato K, Medori MC, Beccari T, Samaja M, Connelly ST, Martin D, Morresi A, Bacu A, Herbst KL, Kapustin M, Stuppia L, Lumer L, Farronato G, Bertelli M (2022) Ethical considerations regarding animal experimentation. J Prev Med Hyg 63:E255–E266. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.2S3.2768

Kim Y, Ko J, Shin N, Park S, Lee S-R, Kim S, Song J, Lee S, Kang K-S, Lee J, Jeon NL (2022) All-in-one microfluidic design to integrate vascularized tumor spheroid into high-throughput platform. Biotechnol Bioeng 119:3678–3693. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.28221

Kim JY, Han Y, Jeon BG, Nam MS, Kwon S, Heo YJ, Park M (2023) Development of albumin monitoring system with hepatic hypoxia-on-a-chip. Talanta 260:124592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2023.124592

Kohn DB, Chen YY, Spencer MJ (2023) Successes and challenges in clinical gene therapy. Gene Ther 30:738–746. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-023-00390-5

Kopp B, Khawam A, Di Perna K, Lenart D, Vinette M, Silva R, Zanoni TB, Rore C, Guenigault G, Richardson E, Kostrzewski T, Boswell A, Van P, Valentine C, Salk J, Hamel A (2024) Liver-on-chip model and application in predictive genotoxicity and mutagenicity of drugs. Mutat Res - Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 896:503762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrgentox.2024.503762

Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han K, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, Baron A, Park J, Han G (2018) Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma : a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 391:1163–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1

Lee H, Chae S, Kim JY, Han W, Kim J, Choi Y (2019) Cell-printed 3D liver-on-a-chip possessing a liver microenvironment and biliary system. Biofabrication 11:025001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1758-5090/aaf9fa

Lee G, Kim H, Park JY, Kim G, Han J, Chung S, Yang JH, Jeon JS, Woo DH, Han C, Kim SK, Park HJ, Kim JH (2021) Generation of uniform liver spheroids from human pluripotent stem cells for imaging-based drug toxicity analysis. Biomaterials 269:120529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120529

Lee J, Maji S, Lee H (2023) Fabrication and integration of a low-cost 3D printing-based glucose biosensor for bioprinted liver-on-a-chip. Biotechnol J 18:2300154. https://doi.org/10.1002/biot.202300154

Li X, Xie S, Shen J, Chen S, Yan J (2022a) Construction of functionalized ruthenium-modified selenium coated with pH-responsive silk fibroin nanomaterials enhanced anticancer efficacy in hepatocellular cancer. Process Biochem 122:203–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2022.08.029

Li H, Li J, Zhang Z, Guo Z, Zhang C, Wang Z, Guo Q, Li C, Li C, Yao J, Zheng A, Xu J, Gao Q, Zhang W, Zhou L (2022b) Integrated microdevice with a windmill-like hole array for the clog-free, efficient, and self-mixing enrichment of circulating tumor cells. Microsyst Nanoeng 8:23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-021-00346-y

Lim J, Choi H, Ahn J, Jeon NL (2021) 3D high-content culturing and drug screening platform to study vascularized hepatocellular carcinoma in hypoxic condition. Adv NanoBiomed Res 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/anbr.202100078

Liu X, Lu Y, Qin S (2021) Atezolizumab and bevacizumab for hepatocellular carcinoma : mechanism, pharmacokinetics and future treatment strategies atezolizumab and bevacizumab for hepatocellular carcinoma : mechanism, pharmacokinetics and future treatment strategies. Futur Oncol 17:2243–2256. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2020-1290

Liu J, Feng C, Zhang M, Song F, Liu H (2022b) Design and fabrication of a liver-on-a-chip reconstructing tissue-tissue interfaces, front. Oncol 12:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.959299

Liu Y, Sheng J, Yang C, Ding J, Chan Y (2023) A decade of liver organoids : advances in disease modeling. Clin Model Hepatol 29:643–669. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0428

Liu GR, Quek SS (eds) (2018) The finite element method: a practical course. Butterworth Heinemann. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49971-0

Liu X, Su Q, Zhang X, Yang W, Ning J, Jia K, Xin J, Li H, Yu L, Liao Y, Zhang D (2022a) Recent advances of organ-on-a-chip in cancer modeling research. Biosensors 1–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12111045

Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS (2021) Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3

Lo C-M, Ngan H, Tso W-K, Liu C-L, Lam C-M, Poon RT-P, Fan S-T, Wong J (2002) Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 35:1164–1171. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2002.33156

Lu Z, Priya Rajan SA, Song Q, Zhao Y, Wan M, Aleman J, Skardal A, Bishop C, Atala A, Lu B (2021) 3D scaffold-free microlivers with drug metabolic function generated by lineage-reprogrammed hepatocytes from human fibroblasts. Biomaterials 269:120668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120668

Luo X, Gong Y, Gong Z, Fan K, Suo T, Liu H, Ni X, Ni X, Abudureyimu M, Liu H (2024) Liver and bile duct organoids and tumoroids. Biomed Pharmacother 178:117104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117104

Maia I, Carvalho V, Rodrigues RO, Pinho D, Teixeira S, Moita A, Hori T, Kaji H, Lima RA, Minas G (2022) Organ-on-a-chip platforms for drug screening and delivery in tumor cells: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel) 14:1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14040935

Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L (1996) Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 334:693–699. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199603143341104

McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB (2021) Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 73(Suppl 1):4–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31288

Messelmani T, Le Goff A, Soncin F, Souguir Z, Merlier F, Maubon N, Legallais C, Leclerc E, Jellali R (2024) Coculture model of a liver sinusoidal endothelial cell barrier and HepG2/C3a spheroids-on-chip in an advanced fluidic platform. J Biosci Bioeng 137:64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2023.10.006

Messelmani T, Le Goff A, Soncin F, Gilard F, Souguir Z, Maubon N, Gakière B, Legallais C, Leclerc E, Jellali R (2023) Investigation of the metabolomic crosstalk between liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatocytes exposed to paracetamol using organ-on-chip technology. Toxicology 492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2023.153550

Mirzababaei S, Navaei-Nigjeh M, Abdollahi M, Shamloo A (2023) Liver-on-a-chip. In: Principles of human organs-on-chips. Elsevier Ltd, pp 195–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823536-2.00011-0

Nguyen R, Da Won Bae S, Qiao L, George J (2021) Developing liver organoids from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs): an alternative source of organoid generation for liver cancer research. Cancer Lett 508:13–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2021.03.017

Ortega-Ribera M (2024) Learning about liver regeneration from liver-on-a-chip. Curr Opin Biomed Eng 30:100533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobme.2024.100533

Özkan A, Stolley DL, Cressman ENK, McMillin M, Yankeelov TE, Nichole Rylander M (2023) Vascularized hepatocellular carcinoma on a chip to control chemoresistance through cirrhosis, inflammation and metabolic activity. Small Struct 4. https://doi.org/10.1002/sstr.202200403

Panagiotis N, Chau I (2024) Updates on systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B 44. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_430028

Poddar MS, Chu Y-D, Yeh C-T, Liu C-H (2024) Deciphering hepatoma cell resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors: insights from a Liver-on-a-Chip model unveiling tumor endothelial cell mechanisms. Lab Chip 24:3668–3678. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4lc00238e

Polidoro MA, Ferrari E, Soldani C, Franceschini B, Saladino G, Rosina A, Mainardi A, D’Autilia F, Pugliese N, Costa G, Donadon M, Torzilli G, Marzorati S, Rasponi M, Lleo A (2024) Cholangiocarcinoma-on-a-chip: a human 3D platform for personalised medicine. JHEP Rep 6:100910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100910

Prodanov L, Jindal R, Bale SS, Hegde M, McCarty WJ, Golberg I, Bhushan A, Yarmush ML, Usta OB (2016) Long-term maintenance of a microfluidic 3D human liver sinusoid. Biotechnol Bioeng 113:241–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.25700

Reghupaty S, Sarkar D (2019) Current status of gene therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11091265

Rezaei N (ed) (2023) Cancer treatment: an interdisciplinary approach. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43983-4

Rodríguez-Pena A, Armendariz E, Oyarbide A, Morales X, Ortiz-Espinosa S, Ruiz-Fernández de Córdoba B, Cochonneau D, Cornago I, Heymann D, Argemi J, D’Avola D, Sangro B, Lecanda F, Pio R, Cortés-Domínguez I, Ortiz-de-Solórzano C (2022) Design and validation of a tunable inertial microfluidic system for the efficient enrichment of circulating tumor cells in blood. Bioeng Transl Med 7:e10331. https://doi.org/10.1002/btm2.10331

Rumgay H, Ferlay J, de Martel C, Georges D, Ibrahim AS, Zheng R, Wei W, Lemmens VEPP, Soerjomataram I (2022a) Global, regional and national burden of primary liver cancer by subtype. Eur J Cancer 161:108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.11.023

Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, Laversanne M, McGlynn KA, Soerjomataram I (2022b) Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol 77:1598–1606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021

Saeedabadi K, Tosello G, Calaon M (2022) Optimization of injection molded polymer lab-on-a-chip for acoustic blood plasma separation using virtual design of experiment. Procedia CIRP 107:40–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2022.04.007

Sangro B, Carpanese L, Cianni R, Golfieri R, Gasparini D, Ezziddin S, Paprottka PM, Fiore F, Van Buskirk M, Bilbao JI, Ettorre GM, Salvatori R, Giampalma E, Geatti O, Wilhelm K, Hoffmann RT, Izzo F, Iñarrairaegui M, Maini CL, Urigo C, Cappelli A, Vit A, Ahmadzadehfar H, Jakobs TF, Lastoria S (2011) Survival after yttrium-90 resin microsphere radioembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma across Barcelona clinic liver cancer stages: a European evaluation. Hepatology 54:868–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24451

Sangro B, Sarobe P, Hervás-Stubbs S, Melero I (2021) Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18:525–543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00438-0

Seidi S, Eftekhari A, Khusro A, Heris RS, Sahibzada MUK, Gajdács M (2022) Simulation and modeling of physiological processes of vital organs in organ-on-a-chip biosystem. J King Saud Univ - Sci 34:101710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101710

Sharifi F, Yesil-Celiktas O, Kazan A, Maharjan S, Saghazadeh S, Firoozbakhsh K, Firoozabadi B, Zhang YS (2020) A hepatocellular carcinoma–bone metastasis-on-a-chip model for studying thymoquinone-loaded anticancer nanoparticles. Bio-Design Manuf 3:189–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42242-020-00074-8

Shen P, Jia Y, Zhou W, Zheng W, Wu Y, Qu S, Du S, Wang S, Shi H, Sun J, Han X (2023) A biomimetic liver cancer on-a-chip reveals a critical role of LIPOCALIN-2 in promoting hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Acta Pharm Sin B 13:4621–4637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.04.010

Solan ME, Schackmuth B, Bruce ED, Pradhan S, Sayes CM, Lavado R (2023) Effects of short-chain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) on toxicologically relevant gene expression profiles in a liver-on-a-chip model. Environ Pollut 337:122610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122610

Solovchuk MA, Sheu TWH, Thiriet M, Lin W-L (2013) On a computational study for investigating acoustic streaming and heating during focused ultrasound ablation of liver tumor. Appl Therm Eng 56:62–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2013.02.041

Soltantabar P, Calubaquib EL, Mostafavi E, Ghazavi A, Stefan MC (2021) Heart/liver-on-a-chip as a model for the evaluation of cardiotoxicity induced by chemotherapies. Organs-on-a-Chip 3:100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ooc.2021.100008

Sontheimer-Phelps A, Hassell BA, Ingber DE (2019) Modelling cancer in microfluidic human organs-on-chips. Nat Rev Cancer 19:65–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-018-0104-6

Taha AM, Aboulwafa MM, Zedan H (2022) Ramucirumab combination with sorafenib enhances the inhibitory effect of sorafenib on HepG2 cancer cells. Sci Rep 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21582-w

Tian T, Ho Y, Chen C, Sun H, Hui J, Yang P, Ge Y, Liu T, Yang J, Mao H (2022) A 3D bio-printed spheroids based perfusion in vitro liver on chip for drug toxicity assays. Chin Chem Lett 33:3167–3171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.11.029

Tonon F, Giobbe GG, Zambon A, Luni C, Gagliano O, Floreani A, Grassi G, Elvassore N (2019) In vitro metabolic zonation through oxygen gradient on a chip. Sci Rep 9:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49412-6

Vakili K, Pomposelli JJ, Cheah YL, Akoad M, Lewis WD, Khettry U, Gordon F, Khwaja K, Jenkins R, Pomfret EA (2009) Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: increased recurrence but improved survival. Liver Transplant Off Publ Am Assoc Study Liver Dis Int Liver Transplant Soc 15:1861–1866. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.21940

Versteeg HK, Malalasekera W (2007) An introduction to computational fluid dynamics. The finite volume method, Second. Prentice Hall

Wang W, Li L, Ding M, Luo G, Liang Q (2018) A microfluidic hydrogel chip with orthogonal dual gradients of matrix stiffness and oxygen for cytotoxicity test. BioChip J 12:93–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13206-017-2202-z

WHO (2024a) Global Cancer Observatory (GCO). https://gco.iarc.fr/. Accessed 22 Feb 2024

World Health Organization (WHO) (2024b) Cancer fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. Accessed 23 Jul 2024

Wu G, Wu J, Li Z, Shi S, Wu D, Wang X, Xu H, Liu H, Huang Y, Wang R, Shen J, Dong Z, Wang S (2022) Development of digital organ-on-a-chip to assess hepatotoxicity and extracellular vesicle-based anti-liver cancer immunotherapy. Bio-Design Manuf 5:437–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42242-022-00188-1

Xie X, Maharjan S, Kelly C, Liu T, Lang RJ, Alperin R, Sebastian S, Bonilla D, Gandolfo S, Boukataya Y, Siadat SM, Zhang YS, Livermore C (2022) Customizable microfluidic origami liver-on-a-chip (oLOC). Adv Mater Technol 7:2100677. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202100677

Xie X, Zhao J, Liu T, Li L, Qin Y, Song X, Ge Y, Zhao J (2023) Label-free and real-time impedance sensor integrated liver chip for toxicity assessment: mechanism and application. Sensors Actuators B Chem 393 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2023.134282

Xue P, Zhang L, Guo J, Xu Z, Kang Y (2016) Isolation and retrieval of circulating tumor cells on a microchip with double parallel layers of herringbone structure. Microfluid Nanofluid 20:169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10404-016-1834-y

Yang Y, Chen Y, Wang L, Xu S, Fang G, Guo X, Chen Z, Gu Z (2022) PBPK Modeling on organs-on-chips: an overview of recent advancements. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.900481

Yang JD, Roberts LR (2010) Hepatocellular carcinoma: a global view. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 7:448–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2010.100

Yao T, Zhang Y, Lv M, Zang G, Ng SS, Chen X (2021) Advances in 3D cell culture for liver preclinical studies. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 53:643–651. https://doi.org/10.1093/abbs/gmab046

Zhang X, Xu X, Ren Y, Yan Y, Wu A (2021) Numerical simulation of circulating tumor cell separation in a dielectrophoresis based Y-Y shaped microfluidic device. Sep Purif Technol 255:117343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2020.117343

Zhao X, Yang J, Wang X, Chen L, Zhang C, Shen Z (2022) Inhibitory effect of aptamer-carbon dot nanomaterial-siRNA complex on the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by interfering with FMRP. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 174:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2022.03.013

Zhou Q, Patel D, Kwa T, Haque A, Matharu Z, Stybayeva G, Gao Y, Diehl AM, Revzin A (2015) Liver injury-on-a-chip: microfluidic co-cultures with integrated biosensors for monitoring liver cell signaling during injury. Lab Chip 15:4467–4478. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5LC00874C

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the project 2022.06207.PTDC (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.06207.PTDC) and PTDC/EEI-EEE/2846/2021 (https://doi.org/10.54499/PTDC/EEI-EEE/2846/2021) through national funds (OE), within the scope of the Scientific Research and Technological Development Projects (IC&DT) program in all scientific domains (PTDC), through the Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P. (FCT, I.P). The authors also acknowledge the partial financial support within the R&D Units Project Scope: UIDB/00319/2020, UIDB/04077/2020, UIDB/04436/2020, UIDB/00532/2020 and LA/P/0045/2020 (ALiCE). Violeta Carvalho thanks for her Ph.D. grant from FCT with reference UI/BD/151028/2021. Raquel O. Rodrigues thanks FCT for her contract funding provided through 2020.03975.CEECIND. Mariana Ferreira thanks FCT her research grant provided through PTDC/EAM-OCE/6797/2020_BI_06_2024_CMEMS.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing – Original Draft: V.C. Literature selection process: V.C., M.F., and R.R. Supervision: R.R., R.L., S.T. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article