Abstract

The recent outbreak of COVID-19 infection started in Wuhan, China, and spread across China and beyond. Since the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic (Mar. 11, 2020), three vaccines and only one antiviral drug (remdesivir) has been approved (Oct. 22, 2020) by the FDA. The coronavirus enters human epithelial cells by the binding of the densely glycosylated fusion spike protein (S protein) to a receptor (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ACE2) on the host cell surface. Therefore, inhibiting the viral entry is a promising treatment pathway for preventing or ameliorating the effects of COVID-19 infection. In the current work, we have used all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate the influence of the MLN-4760 inhibitor on the conformational properties of ACE2 and its interaction with the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2. We have found that the presence of an inhibitor tends to completely/partially open the ACE2 receptor where the two subdomains (I and II) move away from each other, while the absence results in partial or complete closure. The current study increases our understanding of ACE inhibition by MLN-4760 and how it modulates the conformational properties of ACE2.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2), Spike protein, Receptor binding domain (RBD), MLN-4760

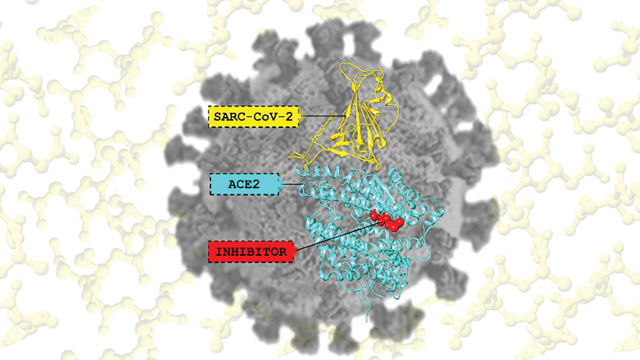

Graphical Abstract

2. INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus appeared in China and caused an acute respiratory disease now called as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus is a betacoronavirus associated with to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) which has led to the name SARS-CoV-2.1 In the last 20 years, the virus is the third known coronavirus that crosses the species barrier and cause highly pathogenic and deadly diseases, namely severe respiratory infection in humans (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2003 and 2012, respectively.2, 3 Due to the quick increase in the number of cases globally, the World Health Organization has declared it a pandemic.4

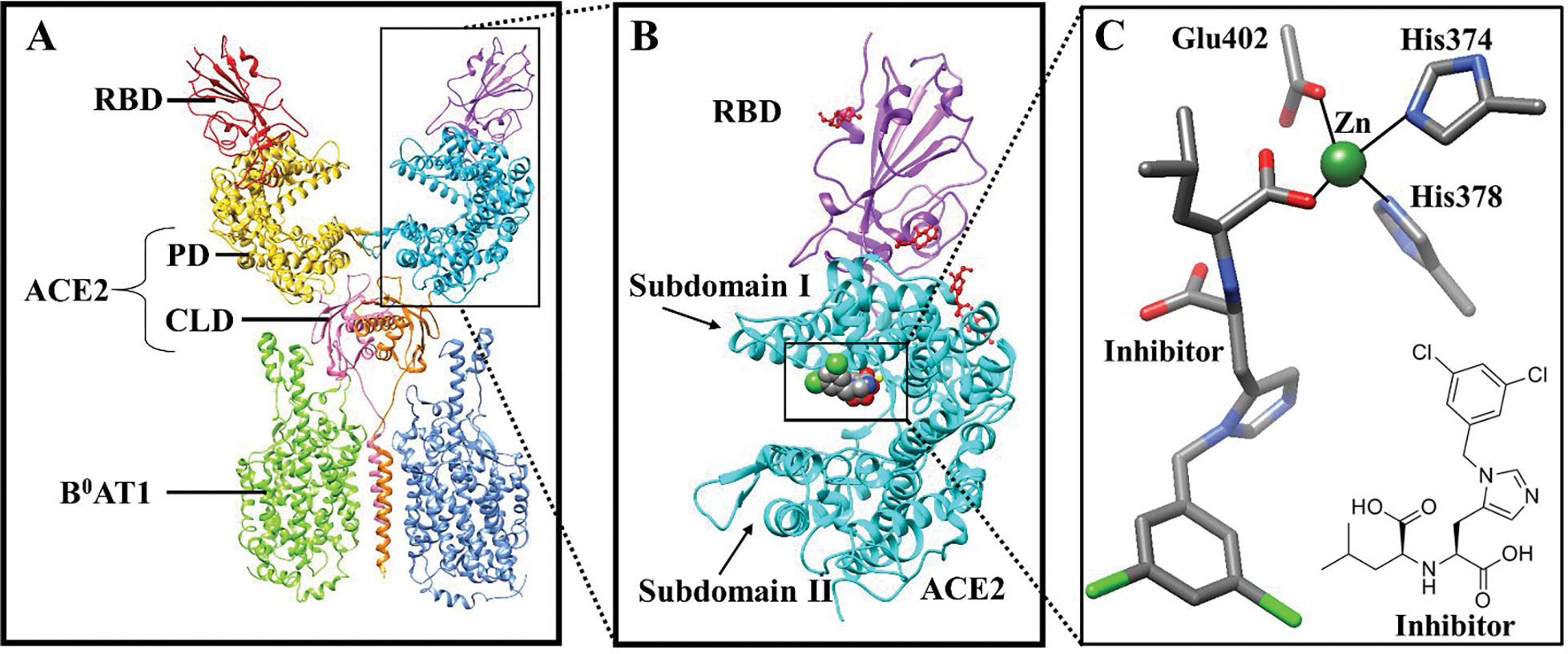

The SARS-CoV-2 enters human epithelial cells through the binding of the densely glycosylated fusion spike protein (S protein) to a receptor (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ACE2) on the host cell surface.5 ACE2 is a zinc-containing metalloenzyme belonging to the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and lowers blood pressure by catalyzing the hydrolysis of angiotensin II into angiotensin (1–7).6 The extracellular region of the ACE2 enzyme contains two domains, i.e., a zinc-containing peptidase domain (PD, residue 19–611) and a collectrin domain (CLD, residue 612–740) shown in Figure 1A.5, 6 The PD is further divided into two subdomains (I and II) (Figure 1B), which form the two sides of a clamshell-like structure with a deep cleft in the center.6 The two subdomains contain the active site and undergo a large substrate-dependent hinge-bending movement to catalyze the hydrolysis of angiotensin II into angiotensin (1–7).6 This movement of ACE2 exists in two orientations: a substrate/inhibitor bound (“closed”) and unbound (“open”) conformation.6 Site-directed mutagenesis study7 highlighted that the active site is composed of a Zn2+ ion coordinated to H374, H378, E402, and water molecule as shown in Figure 1C. In addition, two 2nd coordination shell residues (H345 and H505) aid in the stabilization of the enzyme-substrate complex by forming a network of hydrogen bond interactions.7 According to the proposed catalytic mechanism, the substrate binds to the Zn2+ ion and form an enzyme-substrate complex by forming a tetrahedral intermediate.6 This causes a ~16-degree subdomain hinge-bending movement of subdomain I towards subdomain II.6 Simultaneously, H505 transfers a proton to the nitrogen atom of the scissile peptide resulting in its cleavage.6

Figure 1:

(A) X-ray structure of the RBD-ACE2-B0AT1 complex. RBD: Receptor Binding Domain, PD: Peptidase Domain, CLD: Collectrin-like domain; (B) Inhibitor bound ACE2-RBD complex (RA′O); and (C) Inhibitor bound to the monomeric ACE2 active site.

The binding of the S protein S1 subunit to ACE2 is triggered by the destabilization of the prefusion trimer, inducing the shedding of the S1 and transition of the S2 subunit to a highly stable post-fusion conformation.8, 9 To engage the ACE2 receptor, the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S1 subunit does a hinge-like movement transiently exposing the receptor binding site.6 The hinge-like movement is referred to as a “down” and “up” conformation, where “down” corresponds to receptor-inaccessible state, and “up” corresponds to receptor-accessible state, which is thought to be less stable.5 The RBD contains two parts; (1) a twisted five-stranded antiparallel β sheet (β1, β2, β3, β4, and β7) forming the core; and (2) a receptor binding membrane (RBM, β5, and β6) that binds to the ACE2 surface, Figure S1.5 At the ACE2-RBD interface, a total of 17 residues of the RBM connect to the 20 residues of ACE2.5 Comparative analysis on the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 interaction with the ACE2 enzyme suggested a higher binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 toward ACE2,10–13 while two separate studies proposed that both have a similar binding affinity.14, 15 Any modification in the ACE2 structure should affect this interface and hence the ACE2-RBD binding, presenting an avenue to create therapeutic agents against SARS-CoV-2.

Currently, more than 350 clinical trials are underway out of which remdesivir is the only drug recently approved by FDA for COVID-19 treatment.16 The present pharmacotherapy adopted by FDA is divided into three categories: (1) antiviral therapy e.g. remdesivir;16, 17 (2) immune-based therapy such as human blood-derived products and plasma18–20; and (3) immunomodulators like corticosteroids.16, 21 Antiviral therapy is more effective when applied early in the course of illness before it progresses into the hyperinflammatory state, while the immune-based and immunomodulating therapy is encouraging in the later stages of the disease.17 Therefore, antiviral therapy is more auspicious in combating the disease in comparison to other treatment strategies. It works by restricting the viral replication by inhibiting the entry, and activity of 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) and the papain-like cysteine protease (PLpro) enzymes present in the coronavirus.16, 22–25 The first step of the viral life cycle is its entry into the cell.26 Consequently, blocking the viral entry can successfully prevent/delay the destruction of the immune system and reduce the severity, and at least delay disease progression/death if not fully halting the progression of the infection.26 A relevant example is an antiretroviral drug maraviroc which binds to the human cell membrane receptor preventing the virus-receptor interaction and thereby inhibits the virus entry into the cell.27 Three major approaches have recently been explored to inhibit the coronavirus endocytosis. The first approach is making antibodies that can effectively bind to the S-proteins.15, 28–30 Second is inhibiting the ACE2-RBD interaction by binding a compound at the interface. The third and less investigated approach is the development of inhibitors that modifies the secondary structure of ACE2.

In the COVID-19 drug discovery process, special emphasis is given to drug repurposing (i.e., older drugs, new uses).31–39 As the drugs are already in the market time can be saved by avoiding expensive pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and toxicity studies.40, 41 High-throughput virtual screening (HTVS), molecular docking, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been widely used to explore FDA approved drugs against the S-proteins, ACE2-RBD interface, and main protease. For instance, Choudhary et. al have used HTVS, molecular docking, and MD simulations to investigate the FDA approved LOPAC drug library against RBD and the ACE2 receptor.42 Likewise, Maffucci et al. utilized similar techniques on 3000 existing drugs targeting the main protease and S-proteins.43 Moreover, FDA-approved drugs44, alkamides and piperamides45, amino acids46, peptides47, 48, and various natural products 49–52 have been suggested as potential inhibitors of the coronavirus. In addition, kobophenol A found to block the interaction between ACE2 and RBD with an IC50 of 1.81 μM.51 Till now there are seven vaccines approved by WHO. For instance, Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines composed of nucleoside-modified mRNA encoding a mutated form of the S protein.53, 54 They have shown 95% and 94% efficacy against the disease, respectively.54, 55 On the other hand, Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine is a viral vector vaccine with a lower efficacy of 85%. 56, 57 Other are Janssen Vaccines (non-replicating viral vector)58, CoronaVac (inactivated vaccine)59, BBIBP-CorV (inactivated vaccine)60, Covishiled (viral vector)61.

Due to the late discovery of ACE2 enzyme in the year 200062, 63 (ACE in 195664) there are no clinically approved ACE2 inhibiting drugs. In 2002, Dales et al. developed the first potent and selective picomolar ACE2 inhibitor (MLN-4760)65 causing its hinge-bending inhibition.6 Subsequently, various other ACE2 inhibitors have been proposed experimentally66–69 and computationally51, 70–76. As ACE2 is a component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), the primary goal of these studies was to regulate the blood pressure by modulating the angiotensin II levels in the kidney. However, none of them has so far reached clinical trials despite years of research to date. Before the progression of COVID-19, very few computational studies of ACE2 inhibitors have been performed. Huentelman et al. in 2004 utilized molecular docking approach to identify ACE2 inhibitor (N-(2-aminoethyl)-1 aziridine-ethanamine).71 A different group in 2012 employed a similar protocol to design seven ACE2 inhibitors.77 Recently, a short simulation (100ns) of the MLN-4760 inhibitor effect on the interaction of RBD and ACE2 has been performed by Nami et al. which showed that it neither blocked nor increased the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD to human ACE2 and probably had no effect on the viral entry.78 Cao et al. have designed sequences of few amino acids that can inhibit the interactions between ACE2 and RBD.79 Similarly, Mehranfar et al, designed a sequence of a few amino acids and functionalized with gold nanoparticles as antivirals to prevent the viral entry.80 Raghavan et al. suggested that Metadichol can inhibit the ACE2 enzyme.81 Molecular dynamics studies and binding enthalpy calculations suggest that the binding enthalpy could be reduced for S protein-ACE2 interface in the presence of the MLN-4760 inhibitor.82 This weakening of binding strength was proposed as a result of the destabilization of the interactions between ACE2 and RBD.82 A comparison of ACE2-RBD interactions in the SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 complexes performed by MD simulations shows that the latter has stronger interface interactions.83 Understanding the effect of inhibitors on ACE2 is of key importance in elucidating the ACE2-RBD interaction and in designing new functional inhibitors.

Despite a considerable amount of computational and experimental data, the precise molecular details of the ACE2-RBD interactions and the effect of the inhibitor on ACE2, remain open. To explore these knowledge gaps, we have utilized all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to study the influence of the MLN-4760 inhibitor on the conformational properties of ACE2 and its interaction with the RBD of SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, different conformations (open and closed) of the ACE2 enzyme have also been explored. With these insights, we present a model of how an ACE2 inhibitor can affect its structure and hence, its interaction with the spike protein and ultimately blocking the virus entry. The current analysis will increase our understanding of ACE inhibition by MLN-4760 and will explore how these inhibitors alter the nature of the ACE2/SARS-CoV-2 interface and if exploiting conformational changes at this interface might affect SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. In what follows we first discuss the computational protocol, followed by a detailed analysis of the effect of the inhibitor on the ACE2 and ACE2-RBD interface. Finally, the opening and closing mechanism of the ACE2 enzyme has been proposed.

3. COMPUTATIONAL DETAILS

3.A. MODELING

The crystal structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain (RBD) bound to the ACE2 receptor was obtained from the protein data bank (PDB ID: 6M0J)5. In this ACE2-RBD structure, four additional N-acetyl-β-glucosaminide (NAG) glycans linked to ACE2 N90, N322, and N546 and RBD N343 were also present. These glycans are suggested to control the conformational plasticity of the RBD.84–86 In addition, the effect of N-glycan size was also analyzed by placing glycans of larger size (Figure S2). Although it is proposed that the N-glycans plays an important structure role in modulating the conformational dynamics of RBD and regulating the ACE2 recognition,84 it does not seem to affect the ACE2-RBD complex once the interaction is formed. The superposition of the RAO and RA′O models to their respective larger N-glycan structures does not show a major structural difference. Figure S3. To this complex, MLN-4760 inhibitor (taken from an inhibitor bound ACE2 structure; PDB ID: 1R4L6) was married into the binding site by aligning the active site residues using the VMD program package87. The hydrogen atoms of the inhibitor were added using the protein preparation wizard from the Schrodinger suite 2019–4,88 resulting in a total net charge of −1. The AM1-BCC charges were calculated using the Antechamber in the AmberTools19,89 and then the GAFF 2.1190 was used to describe the atom types and generate the bonded and nonbonded parameters. The H++ server91 was used to determine the protonation states of the amino acids and a careful examination of charged groups was carried out. The ff14SB92 and GLYCAM 06j-193 force fields were employed in the construction of the topology files for the protein and glycans, respectively. The system was solvated using the TIP3P water94, with a minimum distance of 10 Å between the edge of the cell and solute atoms. Charge neutrality was maintained by adding an appropriate number of Na+ ions. The Zn2+ ion in the active site, the crystalized Cl− ion, and the neutralizing Na+ ions were described by IOD parameter sets95, 96 developed previously in our group. Besides the ACE2-RBD complex, simulations of only ACE2 receptor (open and closed conformations) were also performed. The closed conformation inhibitor-bound ACE2 structure was obtained from the protein data bank (PDB ID: 1R4L6). The disordered segment of collectrin homology domains present in this structure was deleted using the VMD software.87 On the other hand, the open conformation inhibitor bound ACE2 structure was obtained by removing the RBD from the ACE2-RBD complex. To compare the effect of inhibitor on the ACE2 receptor, simulations of the apo form (without inhibitor) of the above three complexes were also performed. Overall, we have simulated six different complexes and for the ease of simplicity the complexes are labeled as; (a) AO: open conformation of ACE2; (b) AC: closed conformation of ACE2; (c) RAO: RBD bound open conformation of ACE2; and their respective inhibitor bound structures (A′O, A′C, RA′). Moreover, the A′C complex exist in two different states, i.e., closed for the first 500ns and open for the last 500ns. Therefore, in this paper the closed state of A′C is labelled as A′C1 and the open state is labelled as A′C2.

3.B. MOLECULAR DYNAMIC SIMULATIONS

The molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the AMBER 1889 program package. For each simulation, five steps of minimization were first performed to remove close contacts. The first step minimizes the water molecules and counterions, with the protein restrained. In the second, third, and fourth steps the heavy atoms, backbone heavy atoms, and backbone carbon and oxygen atoms of the protein were restrained, while the last step minimizes the entire system. Each minimization step consisted of 10000 cycles of steepest descent and 10000 cycles of conjugate gradient minimization. Afterward, the system was heated from 0 to 300 K gradually for 1 ns under constant NVT condition. The solute was restrained using a 5 kcal/mol·Å2 restraining potential. Finally, the system was equilibrated at 300 K for 6 ns employing the NPT ensemble, with the restraining potential gradually released. Finally, 1μs of sampling at 300 K under constant NPT condition was performed. The Langevin thermostat with a collision frequency of 2 ps−1 was used to control the temperature, and the Berendsen barostat with a pressure relaxation time of 5 ps was used for the pressure control. The time step was 2 fs and the nonbonded cutoff of 10 Å. The SHAKE97 algorithm was used to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms. We conducted two simulations each for all systems.

2.C. SIMULATION ANALYSIS

The electrostatic surface potential (ESP) of the inhibitor was computed at the B3LYP98/6–31G(d)99 level using the Gaussian 16 program100. Cluster analysis was utilized to obtain the most representative structures from the MD simulations. The hydrophobicity surface potential of the complexes was obtained using the UCSF Chimera program101. Porcupine plots obtained from the PyMOL program102 were utilized to explore modes of protein motion. The Maestro software103 was used to create the 2D interaction diagram between the enzyme and the inhibitor. To examine the secondary structure of the protein, we used the Define Secondary Structure of Proteins (DSSP) algorithm. The helical wheel projection of α2 and α3 helices of the ACE2 receptor was obtained from the NetWheel online web server.104 The VMD87, Schrodinger suite 2019–488, and UCSF Chimera101 programs were used for the visualization of the MD trajectories and preparation of the figures used in this study.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We have used 1 μs long all-atom MD simulations to investigate the interaction of the peptidase domain (PD) of the ACE2 enzyme with the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Experimental studies have suggested that the RBD interacts strongly with the ACE2. These strong interactions are mediated mainly through - electrostatic complementarity (indicated by the hydrophobicity surface (Figure S4)), hydrogen bonding, and hydrophilic interactions. Finally, to compare these results different conformations of ACE2 (i.e., open and closed state) were also elucidated. The analysis of the root-mean-square-deviations (RMSDs) confirmed the equilibration of all the complexes (i.e., AO, AC, RAO) and their respective inhibitor-bound structures (i.e., A′O, A′C, RA′O) within the simulation time (Figure S5). The interactions and structural changes in the ACE2 enzyme and RBD have been discussed by comparing the secondary structures, non-covalent interactions, hydrogen bonding, root-mean-square-fluctuations (RMSF), helical wheel projection, and PCA.

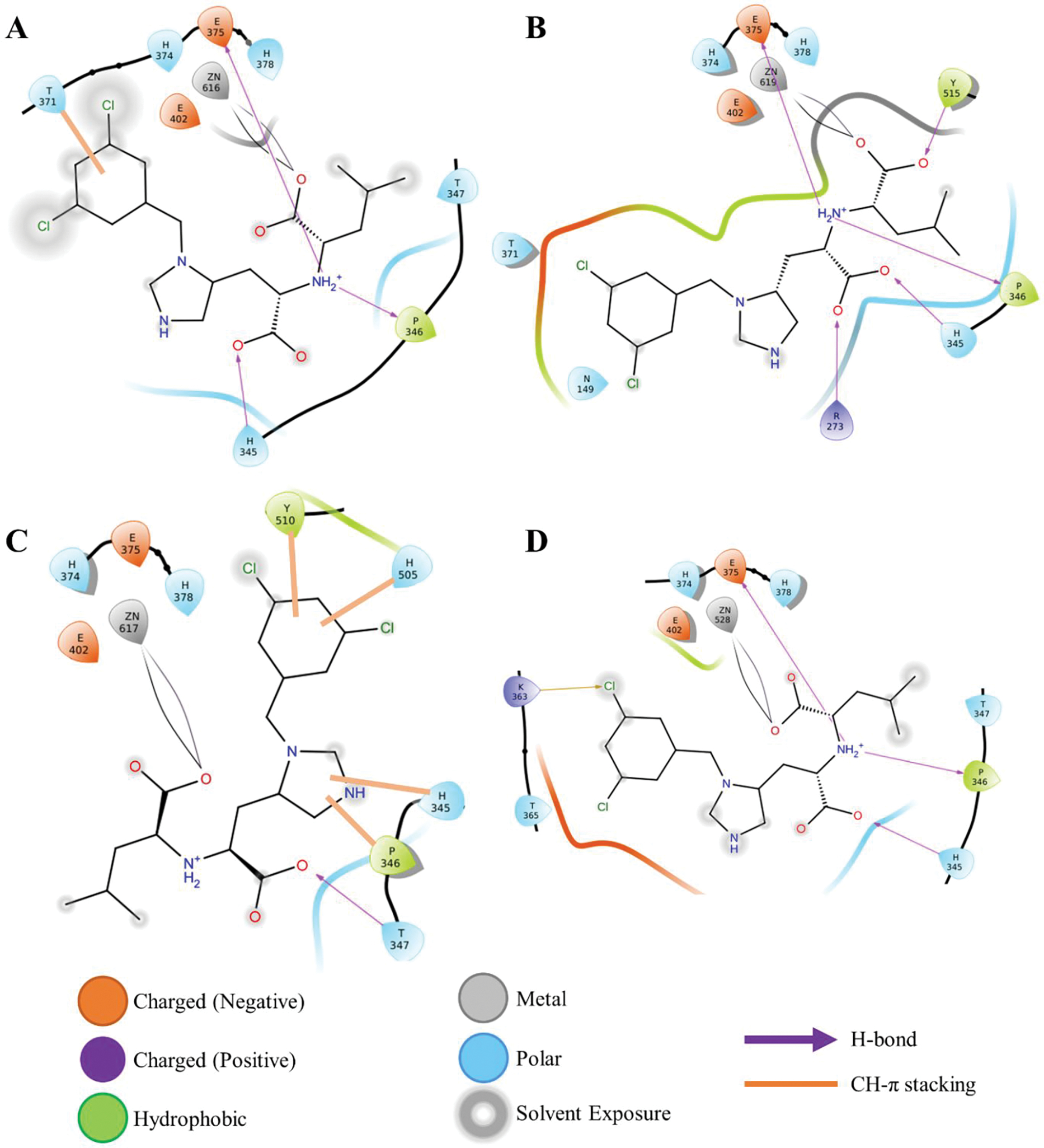

3.A. BINDING MODE OF INHIBITOR

Continuing the analysis of the MD trajectories, we evaluated the specific interactions between the MLN-4760 inhibitor and ACE2 receptor. MLN-4760 is a negatively charged His-Leu mimetic inhibitor with an imidazole ring, an isobutyl side chain, two carboxylate groups, and a dichlorobenzyl group (Figures 1C and S6).65 The imidazole ring mimics His, isobutyl as Leu side chain, Leu carboxylate group binds to the Zn2+ ion while His carboxylate group mimics the zinc-bound tetrahedral intermediate formed during the peptide hydrolysis. The inhibitor binds to the active site located on the subdomain I of ACE2. Gangadevi et al. have shown that a natural compound Kobophenol A is an inhibitor with an IC50 of 1.81 μM which they suggests bind in the hydrophobic cavity (between the two clamshells) of ACE2.51 In the RA′O complex, on inhibitor binding, the 3,5-dichlorobenzyl and isobutyl side chains get exposed to the solvent while the two carboxyl groups were buried inside the binding cleft to interact with the active site (Figure 2D), this is because the open conformation of ACE2 allows water molecules to access the active site, as shown in Figure S7. Likewise, in other ACE2 open conformations [A′O and A′C2], the 3,5-dichlorobenzyl and isobutyl side chains were solvent-exposed, and the carboxyl groups were buried (Figure 2A–D). To accommodate the inhibitor, the active site residues fluctuate, and the magnitude depends on the change in the ACE2 conformational state (i.e., changing from closed to open form). For instance, in the RA′O (partial ACE2 opening) and A′C2 (complete opening of ACE2) complexes, major fluctuations were observed in the active site residues, Figures 2 and S8. This is not surprising since in these structures the ACE2 is changing from one state to another. On the other hand, in A′O and A′C1 complexes, almost no fluctuations were identified in the active site residues, Figure S8. Close inspection of the RA′O 2D graph (Figure 2D) of the residues located within 6 Å of the negatively charged inhibitor highlighted that the binding is likely to be driven by its interaction with the Zn2+ ion, H345, P346, T347, K363, T365, and E375, indicating their active role in binding. These residues form four hydrogen bonds with the inhibitor. Importantly, residue H345, suggested as a hydrogen bond donor/acceptor in the formation of the tetrahedral peptide intermediate,7, 67 forms a hydrogen bond (1.8 Å) interaction with the carboxyl group of the inhibitor. However, residue H505 proposed to stabilize the reactant during catalysis7, was at ~6.1 Å from the inhibitor (Figure S9). This is because RA′O is in open state making the H505 move far from vicinity of the inhibitor. In the A′O complex, three hydrogen bonds were found while five bonds were detected in A′C1 and only one in A′C2. Again, this difference is due to the change of the ACE2 state (from closed to open) due to inhibitor binding. Interestingly, in the A′C complex, the inhibitor binding causes a conformational change in the structure of the ACE2 protein that eventually leads to the opening of the two subdomains and subsequent water flux into the active site. In this structure, for the first 500ns, the inhibitor was planar and ACE2 was in a closed conformation while for the rest of the 500ns the inhibitor undergoes an angle rotation promoting the opening of the ACE2 flaps, (Figure S10). The angle rotation in the inhibitor results in the loss of four H-bonds and the formation of four CH-π interactions between the active site and inhibitor.

Figure 2:

ACE2-inhibitor 2D interaction graph; (A) ACE2 open complex (A′O); (B) ACE2 closed complex (A′C1); (C) ACE2 open complex (A′C2); and (D) ACE2-RBD complex (RA′O).

Overall, the binding of the inhibitor results in the reorganization of the active site and the movement of the alpha-helix (α1-α4) chains promoting complete/partial opening of the ACE2 receptor.

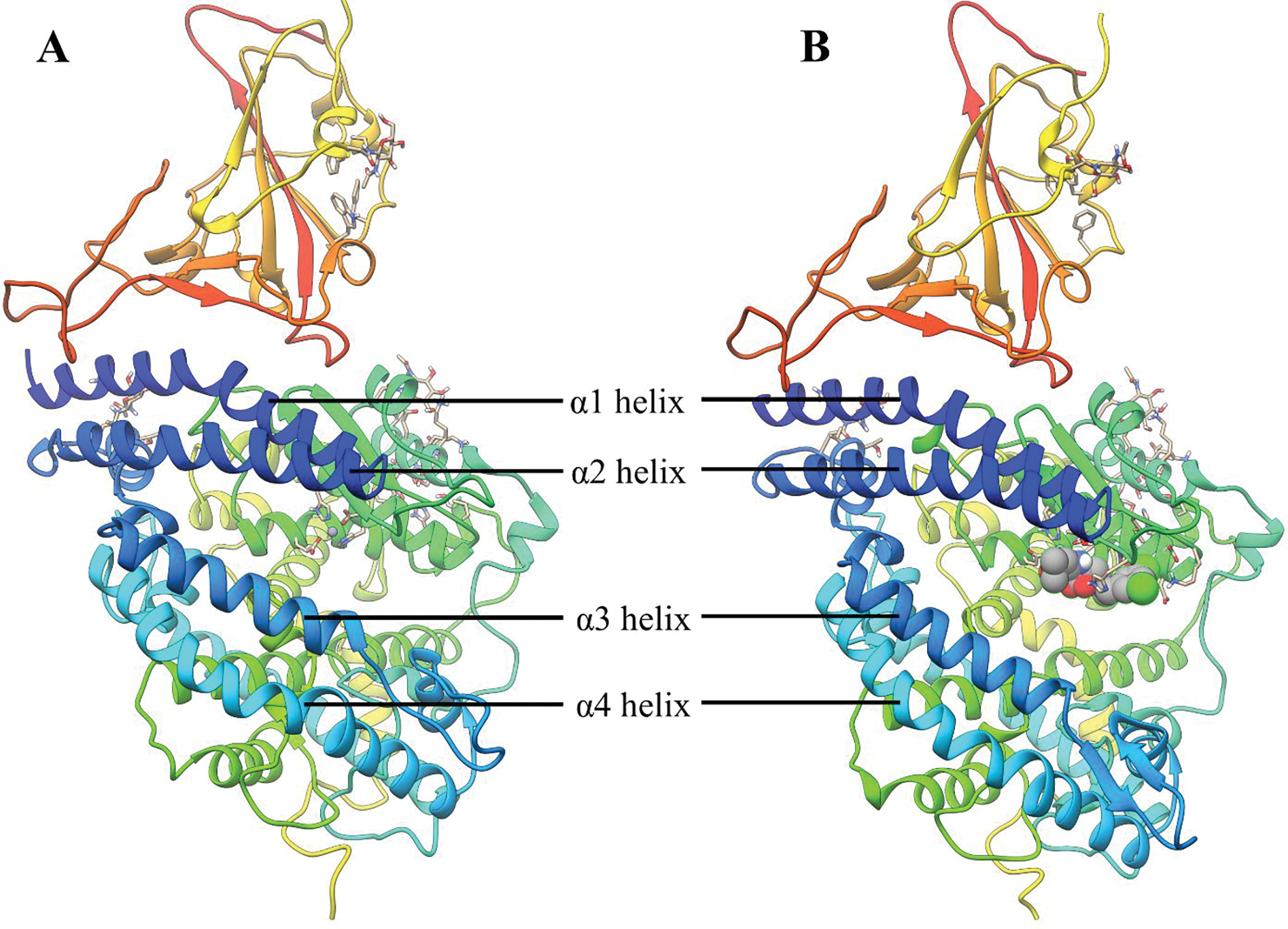

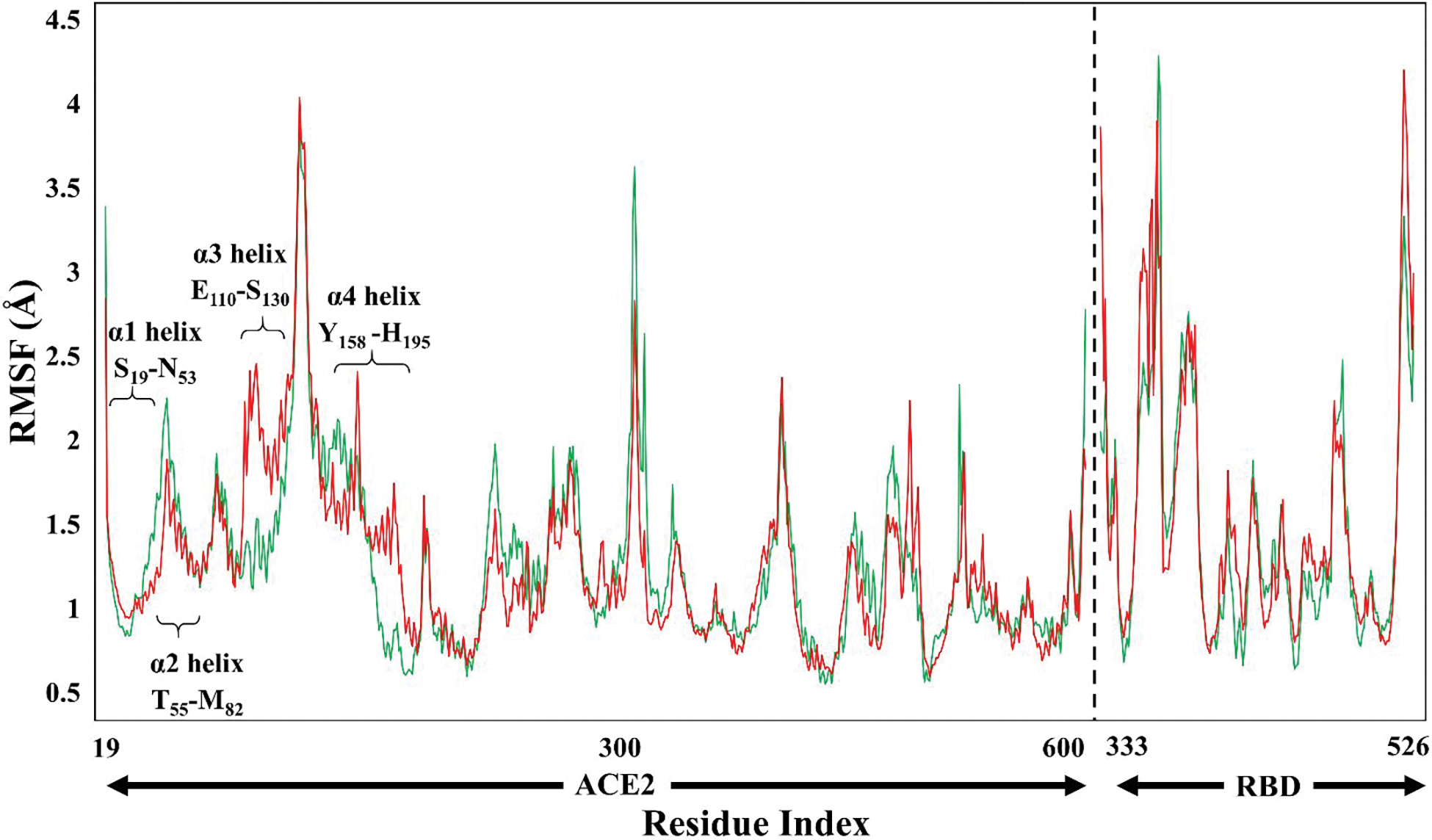

3.B. FLUCTUATIONS IN ACE2 DUE TO INHIBITOR BINDING

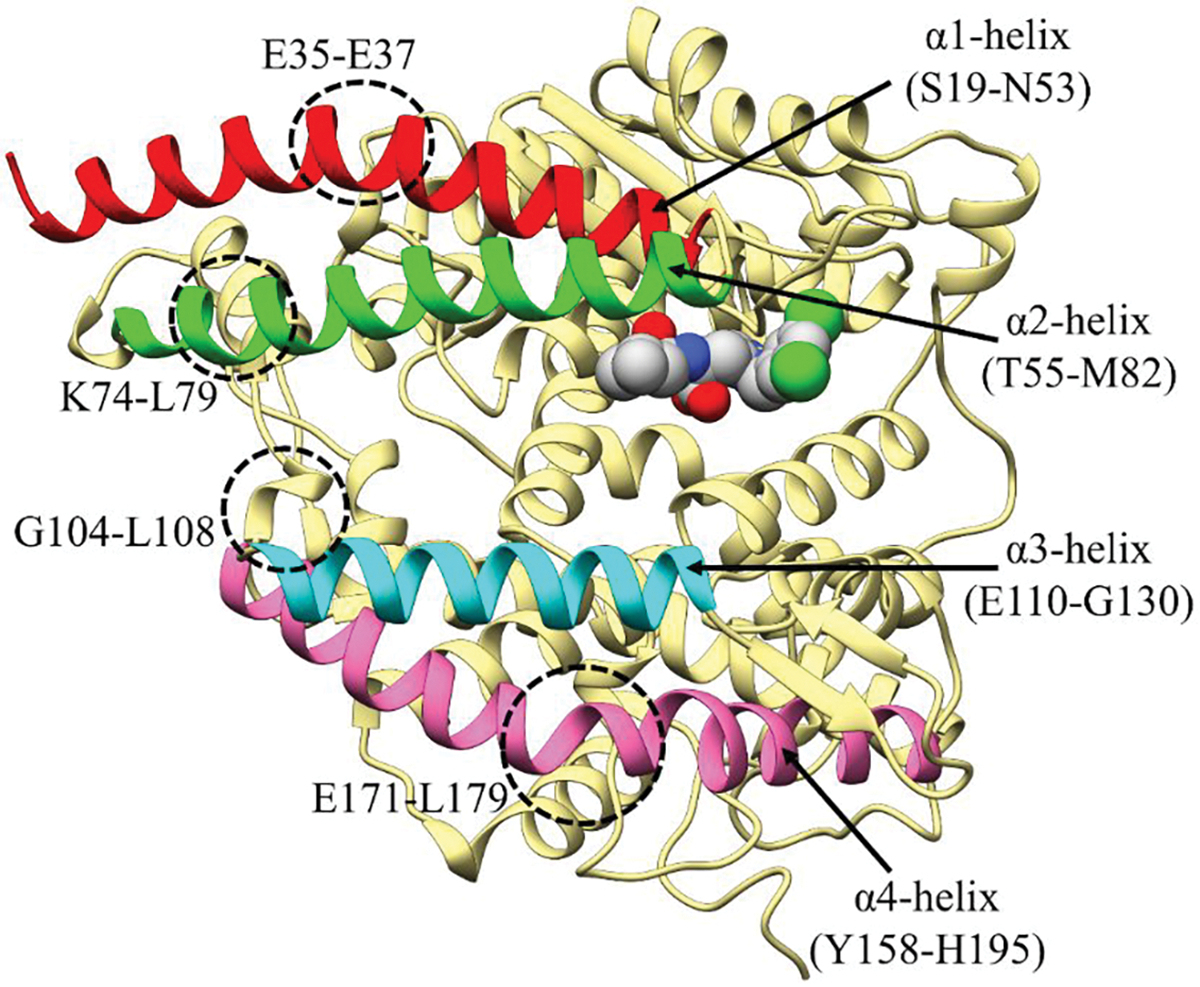

In the open conformation of the ACE2, the upper and the lower subdomains are ~13 Å apart while in the closed conformation the two subdomains come close to each other.6 The most representative structure of the RA′O complex obtained from the last 800ns simulation is shown in Figure 3B. In all the simulations, fluctuations were observed in the subdomain I and II of the ACE2 receptor. These fluctuations were also detected on the RMSF and porcupine plot of the complexes, Figures 4 and S10. Subdomain I is composed of the α1 (S19-N53) and α2 (T55-M82) helices and subdomain II contains the α3 (E110-G130) and α4 (Y158-H195) helices (see Figure 5). Even though the complex fluctuates during the simulation, the overall structure of the RA′O complex remained the same, i.e., ACE2 in the open conformation. Similarly, Kobophenol A also shows minor fluctuations in the ACE2 enzyme and the overall ACE2-RBD complex structure remained the same.51 A superposition of the equilibrated (red) and X-ray (blue) structures showed a minor displacement of residues in the α3 helix highlighted with yellow arrows in Figure S11. On the other hand, in the RAO complex, in the absence of an inhibitor, ACE2 becomes partially closed (Figure 3A). The yellow arrows on the superposition of the most representative (red) and X-ray structure (blue) display the partial closing of the ACE2 receptor (RMSD = 2.2 Å) (Figure S11C).

Figure 3:

Equilibrated structure of; (A) ACE2-RBD (RAO); and (B) ACE2-RBD-Inhibitor (RA′O) complex.

Figure 4:

Root-mean-square-fluctuations (RMSF) of the RAO (green) and RA′O (red) complexes.

Figure 5:

Fluctuations observed in the ACE2 enzyme.

In addition, the superposition of the RAO and RA′O models showed a structural difference between these two complexes with an RMSD of 2.4 Å (see Figure S11A). Another difference between the two complexes was detected in the RMSF graph indicating a difference in fluctuation in the α3 and α4 helix, labeled in Figure 4. The partial differences between the two complexes (RAO and RA′O) could be related to the binding of the MLN-4760 inhibitor to the ACE2 enzyme. In the MD simulations, multiple second coordination shell residues get reoriented upon inhibitor binding, stabilizing the ACE2–inhibitor complex either through direct or water-mediated non-covalent interactions. These interacting residues are shown in Figure 2. As discussed in section 3a, in the A′C complex, the presence of an inhibitor causes an opening of the ACE2 flaps during the simulation. A reasonably clear distinction can be made between its open and closed structures shown in Figure S10. The RMSD obtained by the superposition of these two structures (A′C1 and A′C2) was 3.7 Å. On the other hand, in the AC complex, the ACE2 receptor remains closed during the entire simulation. Similarly, in the AO and A′O complexes, the structure of the ACE2 receptor remains open. The computed RMSD values with their respective X-ray structures were quite low, i.e., 2.8, 2.5, 2.3, 2.4 Å for AO, AC, A′O, and A′C, respectively. All the evidence suggests that the inhibitor tends to open the ACE2 complex while the absence results in its closure or partial closure.

3.C. ACE2-RBD INTERFACE INTERACTIONS

The binding of RBD to ACE2 is a crucial step in the entry of the coronavirus to the epithelial cell.15 The binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 is ~10 to ~20 times higher in comparison to SARS-CoV10 and could be one of the many factors contributing to the worldwide spreading of the disease. These strong interactions are mediated mainly through electrostatic complementarity, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions as suggested by hydrophobic surface maps (Figure S4). The RBD interacts mainly through the α helix (α1 and α2) and loops (I and II) of the ACE2 receptor, Figure 3. Overall, in the RAO complex, 25 hydrogen bonds and four CH-π interactions were observed at the interface, while at the RA′O interface 24 hydrogen bonds and three CH-π interactions were detected (see Table 1). Major changes in the interactions were recognized only in the α1 helix, while on the α2 helix and loop I the interactions were almost the same. On the α1 helix, 13 interactions (i.e., eleven hydrogen bonds and two CH-π interactions) were observed in the RAO complex, while only 10 interactions (i.e., nine hydrogen bonds and one CH-π interaction) were detected in the RA′O complex. On the α1 helix of RA′O complex, hydrogen bond interactions between S19-S477, E37-Y505, and D38-Y449 were lost during the simulation, while new interactions between Q24-G476, D30-K417, and K31-Q493 were formed. The change in the residue interactions is assumed to be due to the opening and partial closing of the ACE2 receptor. In both the RAO and RA′O complexes, the α2 helix, formed only one hydrogen bond (Y83-N487) and two CH-π interactions (M82-F486 and Y83-F486) with the RBD. Similarly, on loop II, the number of interactions in both complexes remained the same.

Table 1:

Hydrogen bonds and CH-π interactions (in Å) between the ACE2 and inhibitor.

| RA0 | H-Bond (Å) | RA′0 | H-Bond (Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 helix | S19-S477 | 3.00, 3.35 | ||

| Q24-A475 | 2.00 | Q24-A475 | 2.11 | |

| Q24-G476 | 2.87 | |||

| D30-K417 | 1.77 | |||

| K31-Q493 | 1.78 | |||

| H34-Q493 | 2.25 | H34-Q493 | 2.70 | |

| E35-Q493 | 1.90 | E35-Q493 | 1.97 | |

| E37-Y505 | 1.78, 2.62 | |||

| D38-Y449 | 1.62 | |||

| D38-Q498 | 1.78 | D38-Q498 | 2.00 | |

| Y41-T500 | 2.27, 2.72 | Y41-T500 | 2.92, 2.73 | |

| α2 helix | Y83-N487 | 1.66 | Y83-N487 | 2.02 |

| Loop I | K353-G496 | 2.42, 2.96, 2.92 | K353-G496 | 2.78, 2.72, 2.84 |

| K353-Q498 | 1.99, 2.97 | K353-Q498 | 1.93, 2.90, | |

| K353-N501 | 2.64 | K353-N501 | 2.45 | |

| K353-Y495 | 2.09 | K353-Y495 | 2.11 | |

| K353-G502 | 1.95 | K353-G502 | 1.97 | |

| D355-T500 | 2.08 | D355-T500 | 1.71, 3.35 | |

| R357-T500 | 2.29, 3.34 | R357-T500 | 2.54, 2.97 | |

| R393-Y505 | 2.78, 3.03 | R393-Y505 | 3.08, 3.43 | |

| CH-π (Å) | CH-π (Å) | |||

| α2 helix | M82-F486 | 3.5 | M82-F498 | 2.7 |

| Y83-F486 | 2.5 | Y83-F486 | 3.3 | |

| Loop II | K31-Y489 | 3.0 | K31-Y489 | 3.0 |

| H34-L455 | 3.0 |

In summary, our calculations highlighted that the hydrogen bond interactions in both complexes played an essential role in stabilizing the binding conformation. However, the fluctuations caused by the inhibitor did not display a major effect on the interface binding as the number of hydrogen bonds remains nearly the same.

3.D. FLUCTUATIONS IN THE RBD

The bending motion detected upon inhibitor binding occurs as subdomain I move to close the gap, and in doing so brings critical residue groups into contact with the substrate/inhibitor. Even after fluctuations in the ACE2 due to this inhibitor, almost no fluctuation in the RBD was observed. A superimposition of the two RBD did not show a major change in the structure. However, the protein’s secondary structure analysis revealed changes in the E340-A344 and V367-S375 residues due to the loss of the alpha-helical property (Figure S13).

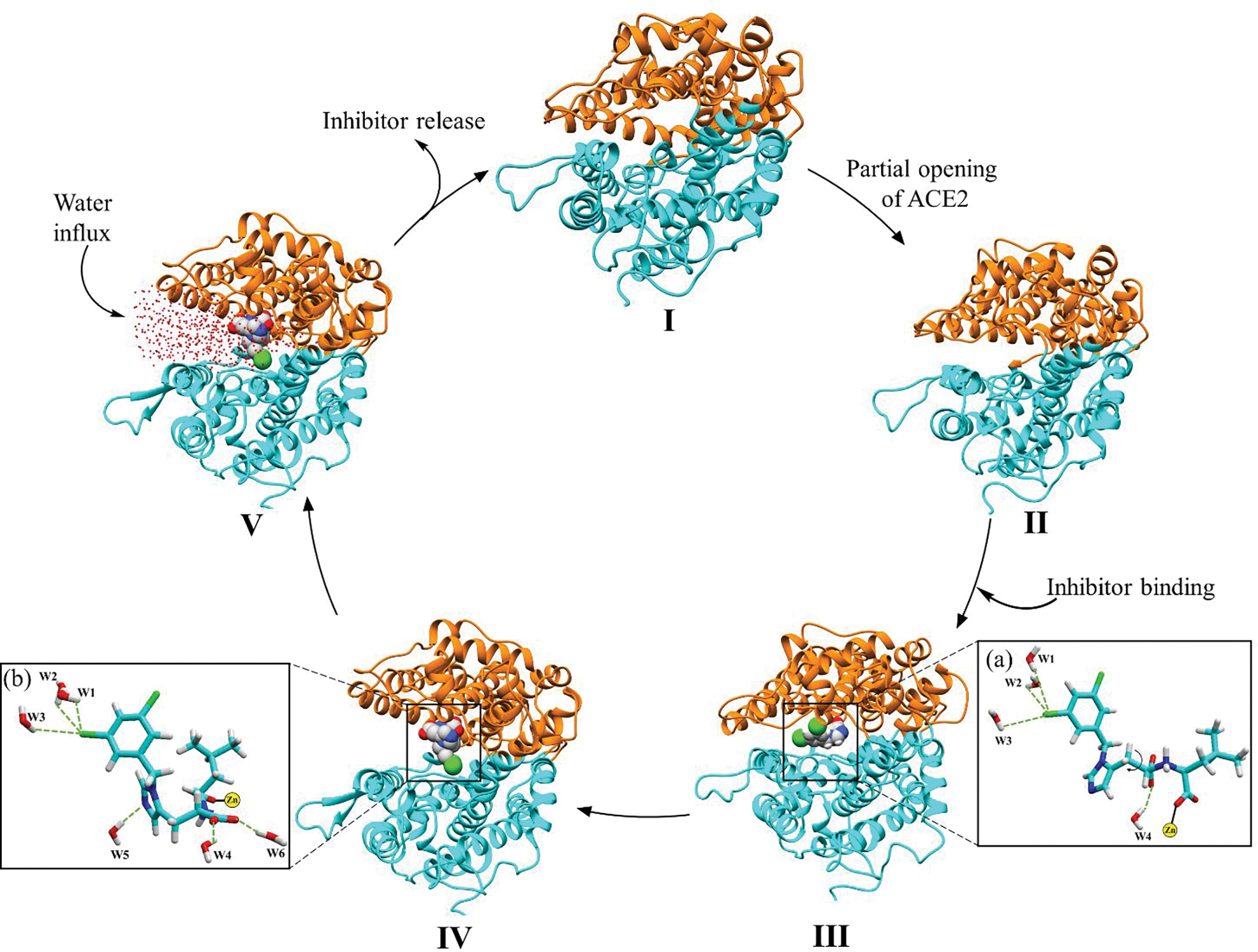

3.E. OPENING AND CLOSING MECHANISM OF ACE2

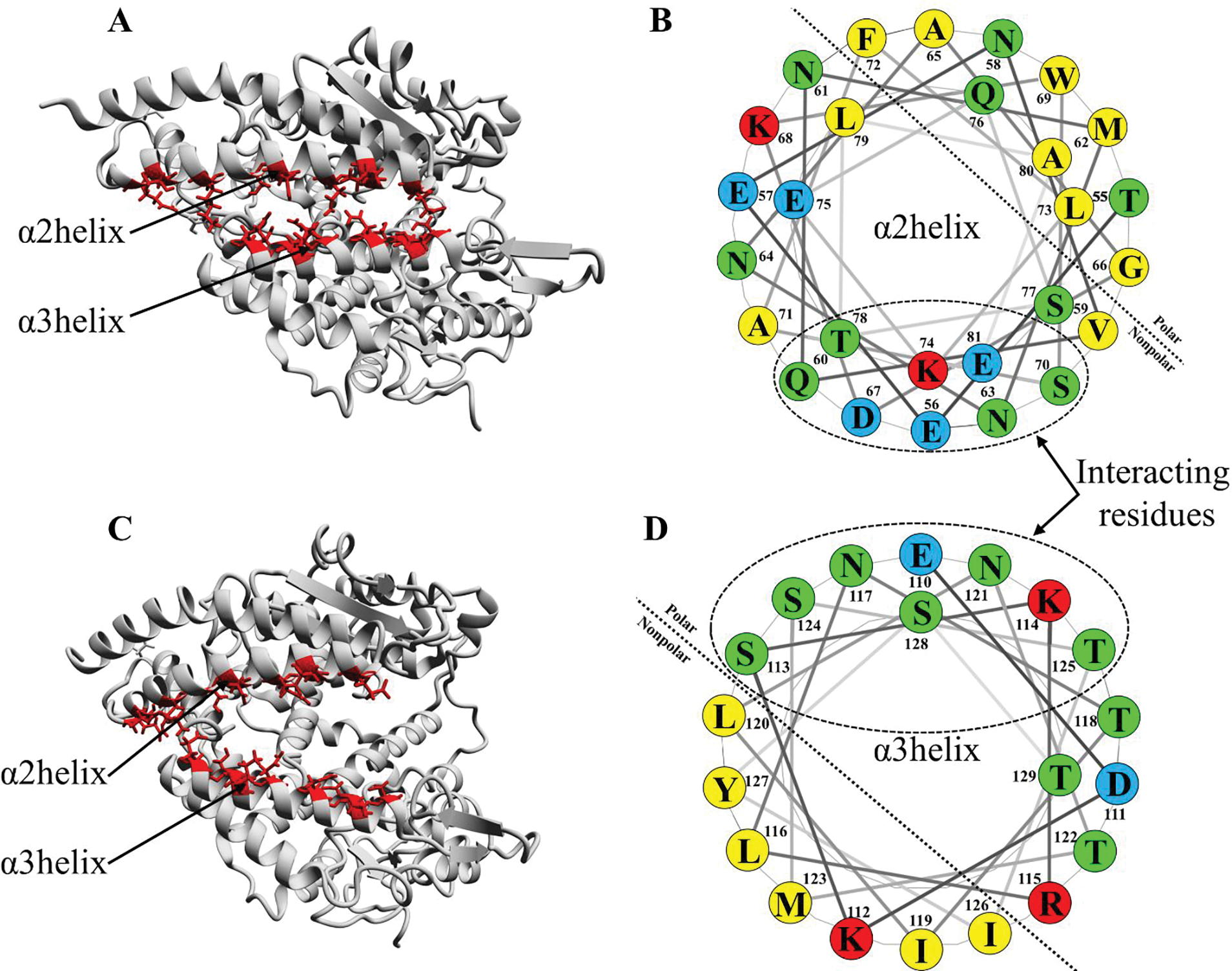

The opening/closing dynamics of ACE2 are characterized by the distance between α2 and α3 helices (i.e., if they are far it is in the open conformation and if they are close it is in closed conformation). The proposed ACE2 opening and closing mechanism is as follows, initially, in an inactive state, the ACE2 is in a closed-form with few water molecules trapped inside the active site cavity (I in Figure 6). In the presence of a substrate/inhibitor, the ACE2 enzyme partially opens, allowing access to the active site (II in Figure 6). Figure S7 shows that the binding of the substrate/inhibitor can only take place in the open conformation of the ACE2 enzyme since in the closed conformation the active site is inaccessible. In the next step, the substrate/inhibitor binds to the Zn ion of the active site (III in Figure 6). Consequently, the substrate undergoes catalytic hydrolysis and leaves the active site cleft. Finally, the polar residues on the α2 and α3 helices come close and switch the gate to a shut state and arrest the enzyme in its closed, inactive conformation (see Figure 7, S12). On the other hand, the inhibitor will remain bound to the metal ion inactivating ACE2. The inhibitor-solvent interaction causes the torsional rotation of the imidazole ring and carboxylate group at the C-C bond (IV in Figure 6) which forms a V shape structure and assists the inhibitor to interact with subdomain II, Figure 6 a and b. Simultaneously, the opening of the ACE2 enzyme also causes the water molecule to enter the cleft allowing higher substrate/inhibitor-solvent interactions (V in Figure 6). A similar flexible/breathing motion has also been suggested to allow substrate binding in the ACE1 enzyme.17 In all simulations, a bending motion (fluctuations) was observed at four regions (circled in Figure 5), i.e., (a) α1 helix (at E35-E37); (b) α2 helix (at K74-L79); (c) α3 helix (at G104-L108); and (d) α4 helix (at E171-L179). Due to these fluctuations, a distinct change in the secondary structure of ACE2 enzyme was detected. Fluctuation in these four sites may be crucial for the opening and closing of the ACE2 enzyme. To obtain further insights into the dynamic behavior of the helices, we monitored the secondary protein structure, which shows that the overall secondary structure was lost at these specific locations (see Figure S13).

Figure 6:

Opening and closing mechanism of ACE2.

Figure 7:

(A and C) ACE2 in a closed and open conformation, respectively. The polar residues on the α2 helix (red color) interact with the polar residues on α3 helix (red color) via hydrogen bonds; (B and D) helical wheel projection of α2 and α3 helix, respectively. The interacting polar residues are shown in the dotted circle.

Additionally, to the above-mentioned fluctuations in ACE2, the opening/closing mechanism also depends on the interaction between α2 and α3 helix. The polar residues on the two helices are facing each other, which facilitate interactions with the two anionic surfaces and help in the opening and closing of the ACE2 clamp by forming direct or water-mediated hydrogen bond interactions. The helical wheel projection of α2 and α3 helix displaying its amphipathic character is shown in Figure 7. Based on the results, we propose that the distribution of polar amino acid residues on one side of the helix is an important parameter for the clamshell mechanism of ACE2. Although further molecular analysis is required to establish a full angiotensin II binding and cleavage cycle, the open and closure of ACE2 in the present analysis already indicate that a significant conformational change is required for the inhibition activity of the ACE2 enzyme.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In the present MD simulation study, molecular interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 S-protein RBD and ACE2 receptor has been investigated. In addition, the role of inhibitor on the dynamic transformation of the ACE2 and RBD, and their interface has been elucidated. According to our MD simulations, the process is initiated by the binding of a potent ACE2 inhibitor (MLN-4760) to the ACE2 receptor active site. To accommodate the inhibitor the ACE2 receptor should be in an open state. The binding is driven by interactions with the positively charged Zn2+ ion and second coordination shell residues present in the active site. The most representative structure of the complexes shows that the chemical nature of the inhibitor causes fluctuations in the surrounding residues causing different conformational dynamics in both RAO and RA′O complexes. The presence of an inhibitor tends to open the ACE2 receptor where the two subdomains (I and II) move away from each other, while the absence results in partial closure. These results were supported by the RMSF, the secondary structure of the protein, and porcupine plots. Furthermore, the difference in the angle of the ACE2 clam, caused by the shrinking of the distance between α2 and α3, explicitly indicated the flexibility of the helices. Although our MD simulations supported the role of inhibitor in the modification of ACE2 structure, it does not demonstrate major changes in the coordination interactions between ACE2 and RBD. The number of hydrogen bonds interactions on their interface remains the same, i.e., 25 and 23 in RAO and RA′O, respectively. Clarification of the structure-function relationship of the ACE2 and ACE2-RBD complex will not only facilitate the understanding of the ACE2 enzyme and its interactions with RBD but also aid in drug discovery of the ACE2 inhibitors against coronavirus.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and the high-performance computer center (iCER HPCC) at Michigan State University.

Funding:

This work was supported in part by a NIH grant (award number GM130641).

Abbreviations

- RBD

Receptor Binding Domain

- PD

Peptidase Domain

- ACE2

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2

Footnotes

Notes: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Requirements for existing software applies to this manuscript: software used for MD simulations is AMBER18 available at http://ambermd.org/. The ACE2-inhibitor 2D interaction graph was prepared by Schrodinger suite 2019–4, provided by high-performance computer center (iCER HPCC) at Michigan State University. The helical wheel projection of α2 and α3 helices of the ACE2 receptor was obtained from the NetWheel online web server at http://lbqp.unb.br/NetWheels. The restart and topology files are freely accessible at https://github.com/gauravsharmamsu/COVID_Research.git. Given their large dimensions, full trajectories are available upon request.

6. REFERENCES

- 1.Hui DS; Azhar EI; Madani TA; Ntoumi F; Kock R; Dar O; Ippolito G; Mchugh TD; Memish ZA; Drosten C, The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 91, 264–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong N; Zheng B; Li Y; Poon L; Xie Z; Chan K; Li P; Tan S; Chang Q; Xie J, Epidemiology and cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong, People’s Republic of China, in February, 2003. The Lancet 2003, 362, 1353–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Groot RJ; Baker SC; Baric RS; Brown CS; Drosten C; Enjuanes L; Fouchier RA; Galiano M; Gorbalenya AE; Memish ZA, Commentary: Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (mers-cov): announcement of the coronavirus study group. Journal of virology 2013, 87, 7790–7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahase E, In; British Medical Journal Publishing Group: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lan J; Ge J; Yu J; Shan S; Zhou H; Fan S; Zhang Q; Shi X; Wang Q; Zhang L, Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Towler P; Staker B; Prasad SG; Menon S; Tang J; Parsons T; Ryan D; Fisher M; Williams D; Dales NA, ACE2 X-ray structures reveal a large hinge-bending motion important for inhibitor binding and catalysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 17996–18007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guy JL; Jackson RM; Jensen HA; Hooper NM; Turner AJ, Identification of critical active-site residues in angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) by site-directed mutagenesis. The FEBS journal 2005, 272, 3512–3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirchdoerfer RN; Cottrell CA; Wang N; Pallesen J; Yassine HM; Turner HL; Corbett KS; Graham BS; McLellan JS; Ward AB, Pre-fusion structure of a human coronavirus spike protein. Nature 2016, 531, 118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu R; Zhao X; Li J; Niu P; Yang B; Wu H; Wang W; Song H; Huang B; Zhu N, Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wrapp D; Wang N; Corbett KS; Goldsmith JA; Hsieh C-L; Abiona O; Graham BS; McLellan JS, Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shang J; Ye G; Shi K; Wan Y; Luo C; Aihara H; Geng Q; Auerbach A; Li F, Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tai W; He L; Zhang X; Pu J; Voronin D; Jiang S; Zhou Y; Du L, Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cellular & molecular immunology 2020, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spinello A; Saltalamacchia A; Magistrato A, Is the Rigidity of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor-Binding Motif the Hallmark for Its Enhanced Infectivity? Insights from All-Atoms Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walls AC; Park Y-J; Tortorici MA; Wall A; McGuire AT; Veesler D, Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian X; Li C; Huang A; Xia S; Lu S; Shi Z; Lu L; Jiang S; Yang Z; Wu Y, Potent binding of 2019 novel coronavirus spike protein by a SARS coronavirus-specific human monoclonal antibody. Emerging microbes & infections 2020, 9, 382–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders JM; Monogue ML; Jodlowski TZ; Cutrell JB, Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. Jama 2020, 323, 1824–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddiqi HK; Mehra MR, COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: A clinical–therapeutic staging proposal. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2020, 39, 405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X; Guo X; Xin Q; Pan Y; Hu Y; Li J; Chu Y; Feng Y; Wang Q, Neutralizing antibodies responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 inpatients and convalescent patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mair-Jenkins J; Saavedra-Campos M; Baillie JK; Cleary P; Khaw F-M; Lim WS; Makki S; Rooney KD; Group CPS; Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. The Journal of infectious diseases 2015, 211, 80–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong J; Tang J; Ye C; Dong L, The immunology of COVID-19: is immune modulation an option for treatment? The Lancet Rheumatology 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horby P; Lim W; Emberson J; Mafham M; Bell J; Linsell L; Staplin N; Brightling C; Ustianowski A; Elmahi E, Effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary report. medRxiv 2020, 22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin Z; Zhao Y; Sun Y; Zhang B; Wang H; Wu Y; Zhu Y; Zhu C; Hu T; Du X, Structural basis for the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by antineoplastic drug carmofur. Nature structural & molecular biology 2020, 27, 529–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh AK; Xi K; Grum-Tokars V; Xu X; Ratia K; Fu W; Houser KV; Baker SC; Johnson ME; Mesecar AD, Structure-based design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of peptidomimetic SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 2007, 17, 5876–5880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y; Liang C; Xin L; Ren X; Tian L; Ju X; Li H; Wang Y; Zhao Q; Liu H, The development of Coronavirus 3C-Like protease (3CLpro) inhibitors from 2010 to 2020. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 112711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ragia G; Manolopoulos VG, Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 entry through the ACE2/TMPRSS2 pathway: a promising approach for uncovering early COVID-19 drug therapies. European journal of clinical pharmacology 2020, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryu W-S, Virus Life Cycle. Molecular Virology of Human Pathogenic Viruses 2017, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulick RM; Lalezari J; Goodrich J; Clumeck N; DeJesus E; Horban A; Nadler J; Clotet B; Karlsson A; Wohlfeiler M, Maraviroc for previously treated patients with R5 HIV-1 infection. New England Journal of Medicine 2008, 359, 1429–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chi X; Yan R; Zhang J; Zhang G; Zhang Y; Hao M; Zhang Z; Fan P; Dong Y; Yang Y, A neutralizing human antibody binds to the N-terminal domain of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 369, 650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baum A; Fulton BO; Wloga E; Copin R; Pascal KE; Russo V; Giordano S; Lanza K; Negron N; Ni M, Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science 2020, 369, 1014–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X; Li R; Pan Z; Qian C; Yang Y; You R; Zhao J; Liu P; Gao L; Li Z, Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cellular & molecular immunology 2020, 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiang Z; Liu J; Shi D; Chen W; Li J; Yan R; Bi Y; Hu W; Zhu Z; Yu Y, Glucocorticoids improve severe or critical COVID-19 by activating ACE2 and reducing IL-6 levels. International Journal of Biological Sciences 2020, 16, 2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghahremanpour MM; Tirado-Rives J; Deshmukh M; Ippolito JA; Zhang C-H; de Vaca IC; Liosi M-E; Anderson KS; Jorgensen WL, Identification of 14 Known Drugs as Inhibitors of the Main Protease of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Y; Hou Y; Shen J; Huang Y; Martin W; Cheng F, Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell discovery 2020, 6, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santos R; Ursu O; Gaulton A; Bento AP; Donadi RS; Bologa CG; Karlsson A; Al-Lazikani B; Hersey A; Oprea TI, A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2017, 16, 19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Touret F; Gilles M; Barral K; Nougairède A; van Helden J; Decroly E; de Lamballerie X; Coutard B, In vitro screening of a FDA approved chemical library reveals potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 replication. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muratov EN; Amaro R; Andrade CH; Brown N; Ekins S; Fourches D; Isayev O; Kozakov D; Medina-Franco JL; Merz KM, A critical overview of computational approaches employed for COVID-19 drug discovery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X; Yu J; Zhang Z; Ren J; Peluffo AE; Zhang W; Zhao Y; Wu J; Yan K; Cohen D; Wang W, Network bioinformatics analysis provides insight into drug repurposing for COVID-19. Medicine in Drug Discovery 2021, 10, 100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galindez G; Matschinske J; Rose TD; Sadegh S; Salgado-Albarrán M; Späth J; Baumbach J; Pauling JK, Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for advancing computational drug repurposing strategies. Nature Computational Science 2021, 1, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su H; Zhou F; Huang Z; Ma X; Natarajan K; Zhang M; Huang Y; Su H, Molecular Insights into Small-Molecule Drug Discovery for SARS-CoV-2. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 9873–9886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pushpakom S; Iorio F; Eyers PA; Escott KJ; Hopper S; Wells A; Doig A; Guilliams T; Latimer J; McNamee C, Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2019, 18, 41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corsello SM; Bittker JA; Liu Z; Gould J; McCarren P; Hirschman JE; Johnston SE; Vrcic A; Wong B; Khan M, The Drug Repurposing Hub: a next-generation drug library and information resource. Nature medicine 2017, 23, 405–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choudhary S; Malik YS; Tomar S, Identification of SARS-CoV-2 cell entry inhibitors by drug repurposing using in silico structure-based virtual screening approach. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maffucci I; Contini A, In Silico Drug Repurposing for SARS-CoV-2 Main Proteinase and Spike Proteins. Journal of Proteome Research 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trezza A; Iovinelli D; Santucci A; Prischi F; Spiga O, An integrated drug repurposing strategy for the rapid identification of potential SARS-CoV-2 viral inhibitors. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutierrez-Villagomez JM; Campos-García T; Molina-Torres J; López MG; Vázquez-Martínez J, Alkamides and piperamides as potential antivirals against the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The journal of physical chemistry letters 2020, 11, 8008–8016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panda SK; Gupta PSS; Biswal S; Ray AK; Rana MK, ACE-2-derived Biomimetic Peptides for the Inhibition of Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Huang X; Pearce R; Zhang Y, Computational design of peptides to block binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to human ACE2. bioRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han Y; Král P, Computational design of ACE2-based short peptide inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2. ACS Nano 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandey P; Rane JS; Chatterjee A; Kumar A; Khan R; Prakash A; Ray S, Targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein of COVID-19 with naturally occurring phytochemicals: an in silico study for drug development. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2020, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen H; Du Q, Potential natural compounds for preventing SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) infection. Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gangadevi S; Badavath VN; Thakur A; Yin N; De Jonghe S; Acevedo O; Jochmans D; Leyssen P; Wang K; Neyts J, Kobophenol A Inhibits Binding of Host ACE2 Receptor with Spike RBD Domain of SARS-CoV-2, a Lead Compound for Blocking COVID-19. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2021, 12, 1793–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mesli F; Ghalem M; Daoud I; Ghalem S, Potential inhibitors of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor of COVID-19 by Corchorus olitorius Linn using docking, molecular dynamics, conceptual DFT investigation and pharmacophore mapping. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walsh EE; Frenck RW Jr; Falsey AR; Kitchin N; Absalon J; Gurtman A; Lockhart S; Neuzil K; Mulligan MJ; Bailey R, Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based Covid-19 vaccine candidates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2439–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polack FP; Thomas SJ; Kitchin N; Absalon J; Gurtman A; Lockhart S; Perez JL; Pérez Marc G; Moreira ED; Zerbini C, Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chagla Z, The BNT162b2 (BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccine had 95% efficacy against COVID-19≥ 7 days after the 2nd dose. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, JC15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voysey M; Clemens SAC; Madhi SA; Weckx LY; Folegatti PM; Aley PK; Angus B; Baillie VL; Barnabas SL; Bhorat QE, Single-dose administration and the influence of the timing of the booster dose on immunogenicity and efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine: a pooled analysis of four randomised trials. The Lancet 2021, 397, 881–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Knoll MD; Wonodi C, Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine efficacy. The Lancet 2021, 397, 72–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oliver SE; Gargano JW; Scobie H; Wallace M; Hadler SC; Leung J; Blain AE; McClung N; Campos-Outcalt D; Morgan RL, The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendation for Use of Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine—United States, February 2021. Morb. Mortal. Weekly Rep. 2021, 70, 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y; Zeng G; Pan H; Li C; Hu Y; Chu K; Han W; Chen Z; Tang R; Yin W, Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18–59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. The Lancet infectious diseases 2021, 21, 181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xia S; Zhang Y; Wang Y; Wang H; Yang Y; Gao GF; Tan W; Wu G; Xu M; Lou Z, Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2021, 21, 39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamal D; Thakur V; Nath N; Malhotra T; Gupta A; Batlish R, Adverse events following ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Vaccine (COVISHIELD) amongst health care workers: A prospective observational study. medical journal armed forces india 2021, 77, S283–S288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tipnis SR; Hooper NM; Hyde R; Karran E; Christie G; Turner AJ, A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 33238–33243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Douglas GC; O’Bryan MK; Hedger MP; Lee DK; Yarski MA; Smith AI; Lew RA, The novel angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) homolog, ACE2, is selectively expressed by adult Leydig cells of the testis. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 4703–4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Skeggs LT Jr; Kahn JR; Shumway NP, The preparation and function of the hypertensin-converting enzyme. The Journal of experimental medicine 1956, 103, 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dales NA; Gould AE; Brown JA; Calderwood EF; Guan B; Minor CA; Gavin JM; Hales P; Kaushik VK; Stewart M, Substrate-based design of the first class of angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) inhibitors. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2002, 124, 11852–11853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mores A; Matziari M; Beau F; Cuniasse P; Yiotakis A; Dive V, Development of potent and selective phosphinic peptide inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2008, 51, 2216–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guy JL; Jackson RM; Acharya KR; Sturrock ED; Hooper NM; Turner AJ, Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2): comparative modeling of the active site, specificity requirements, and chloride dependence. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 13185–13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pedersen KB; Sriramula S; Chhabra KH; Xia H; Lazartigues E, Species-specific inhibitor sensitivity of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and its implication for ACE2 activity assays. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2011, 301, R1293–R1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang L; Sexton DJ; Skogerson K; Devlin M; Smith R; Sanyal I; Parry T; Kent R; Enright J; Wu Q. l., Novel peptide inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 15532–15540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deaton DN; Gao EN; Graham KP; Gross JW; Miller AB; Strelow JM, Thiol-based angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitors: P1 modifications for the exploration of the S1 subsite. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters 2008, 18, 732–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huentelman MJ; Zubcevic J; Hernandez Prada JA; Xiao X; Dimitrov DS; Raizada MK; Ostrov DA, Structure-based discovery of a novel angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitor. Hypertension 2004, 44, 903–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Byrnes JJ; Gross S; Ellard C; Connolly K; Donahue S; Picarella D, Effects of the ACE2 inhibitor GL1001 on acute dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Inflammation research 2009, 58, 819–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Padhi AK; Rath SL; Tripathi T, Accelerating COVID-19 research using molecular dynamics simulation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2021, 125, 9078–9091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pham T-H; Qiu Y; Zeng J; Xie L; Zhang P, A deep learning framework for high-throughput mechanism-driven phenotype compound screening and its application to COVID-19 drug repurposing. Nature Machine Intelligence 2021, 3, 247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cáceres TB; Thakur A; Price OM; Ippolito N; Li J; Qu J; Acevedo O; Hevel JM, Phe71 in type III trypanosomal protein arginine methyltransferase 7 (TbPRMT7) restricts the enzyme to monomethylation. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 1349–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thakur A; Somai S; Yue K; Ippolito N; Pagan D; Xiong J; Ellis HR; Acevedo O, Substrate-Dependent Mobile Loop Conformational Changes in Alkanesulfonate Monooxygenase from Accelerated Molecular Dynamics. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 3582–3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torres JE; Baldiris R; Vivas-Reyes R, Design of Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) Inhibitors by Virtual Lead Optimization and Screening. Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society 2012, 59, 1394–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nami B; Ghanaeian A; Ghanaeian K; Nami N, The effect of ACE2 inhibitor MLN-4760 on the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with human ACE2: a molecular dynamics study. 2020.

- 79.Cao L; Goreshnik I; Coventry B; Case JB; Miller L; Kozodoy L; Chen RE; Carter L; Walls AC; Park Y-J, De novo design of picomolar SARS-CoV-2 miniprotein inhibitors. Science 2020, 370, 426–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mehranfar A; Izadyar M, Theoretical Design of Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles as Antiviral Agents against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The journal of physical chemistry letters 2020, 11, 10284–10289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raghavan P, Metadichol, a novel nano lipid formulation that inhibits SARS-COV-2 and a multitude of pathologicalviruses in vitro. Res Square 2020, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams-Noonan BJ; Todorova N; Kulkarni K; Aguilar M-I; Yarovsky I, An Active Site Inhibitor Induces Conformational Penalties for ACE2 Recognition by the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu H; Lupala C; Li X; Lei J; Chen H; Qi J; Su X, Computational simulations reveal the binding dynamics between human ACE2 and the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Casalino L; Gaieb Z; Goldsmith JA; Hjorth CK; Dommer AC; Harbison AM; Fogarty CA; Barros EP; Taylor BC; McLellan JS, Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Central Science 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arantes PR; Saha A; Palermo G, In; ACS Publications: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sztain T; Ahn S-H; Bogetti AT; Casalino L; Goldsmith JA; Seitz E; McCool RS; Kearns FL; Acosta-Reyes F; Maji S, A glycan gate controls opening of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Nat. Chem. 2021, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Humphrey W; Dalke A; Schulten K, VMD - Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Molec. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sastry GM; Adzhigirey M; Day T; Annabhimoju R; Sherman W, Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design 2013, 27, 221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Case DA, I. Y. B.-S., Brozell SR, Cerutti DS, Cheatham TE III, Cruzeiro VWD, Darden TA,; Duke RE, Giambasu DG,G, Giese T, Gilson MK, Gohlke H, Goetz AW, Greene D, Harris R,; Homeyer N, Y. H., Izadi S, Kovalenko A, Krasny R, Kurtzman T, Lee TS, LeGrand S, Li P, Lin C,; Liu J, T. L., Luo R, Man V, Mermelstein DJ, Merz KM, Miao Y, Monard G, Nguyen C, Nguyen H, A. O., Pan F, Qi R, Roe DR, Roitberg A, Sagui C, Schott-Verdugo S, Shen J, Simmerling CL, J. S., Swails J, Walker RC, Wang J, Wei H, Wilson L, Wolf RM, Wu X, Xiao L, Xiong Y, D. M. Y. a. P. A. K., AMBER 2019, University of California, San Francisco. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang J; Wolf RM; Caldwell JW; Kollman PA; Case DA, Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Anandakrishnan R; Aguilar B; Onufriev AV, H++3.0: automating pK prediction and the preparation of biomolecular structures for atomistic molecular modeling and simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W537–W541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maier JA; Martinez C; Kasavajhala K; Wickstrom L; Hauser KE; Simmerling C, ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kirschner KN; Yongye AB; Tschampel SM; Gonzalez-Outeirino J; Daniels CR; Foley BL; Woods RJ, GLYCAM06: a generalizable biomolecular force field. Carbohydrates. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 622–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jorgensen WL; Madura JD; Swenson CJ, Optimized intermolecular potential functions for liquid hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 6638–6646. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li PF; Roberts BP; Chakravorty DK; Merz KM, Rational design of particle mesh ewald compatible Lennard-Jones parameters for +2 metal cations in explicit solvent. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 2733–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li P; Song LF; Merz KM Jr., Systematic parameterization of monovalent Ions employing the nonbonded model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 1645–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ryckaert JP; Ciccotti G; Berendsen HJC, Numerical-Integration of Cartesian Equations of Motion of a System with Constraints - Molecular-Dynamics of N-Alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977, 23, 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Becke AD, Becke’s three parameter hybrid method using the LYP correlation functional. J. Chem. Phys 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Francl MM; Pietro WJ; Hehre WJ; Binkley JS; Gordon MS; DeFrees DJ; Pople JA, Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarization-type basis set for second-row elements. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1982, 77, 3654–3665. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Frisch M; Trucks G; Schlegel H; Scuseria G; Robb M; Cheeseman J; Scalmani G; Barone V; Petersson G; Nakatsuji H, In; Gaussian, Inc. Wallingford, CT: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pettersen EF; Goddard TD; Huang CC; Couch GS; Greenblatt DM; Meng EC; Ferrin TE, UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.DeLano WL, Pymol: An open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsletter on protein crystallography 2002, 40, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Release S, 1: Maestro. Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY: 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mol AR; Castro MS; Fontes W, NetWheels: A web application to create high quality peptide helical wheel and net projections. BioRxiv 2018, 416347. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.